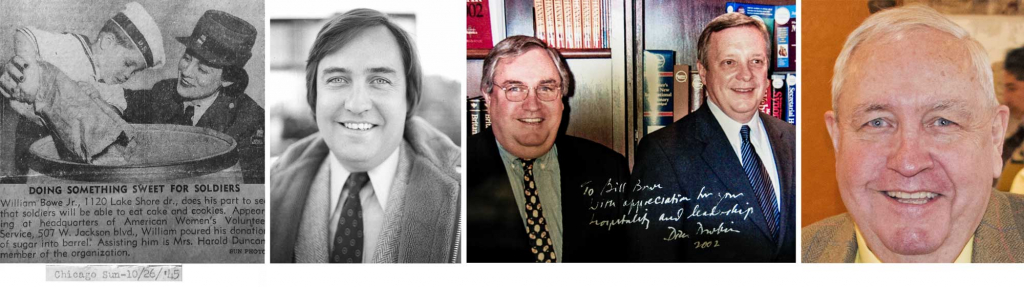

2019 Richard Gwinn Bowe Memorial Lunch

At The Cliff Dwellers: A Remembrance and Celebration of the Life of Richard Gwinn Bowe (1938-2019) with a eulogy from his brother, William J. Bowe, and remarks from his twins, Alexandra & Anson Bowe and his caretaker at the end of life, Estella Machado.

2019-10-12 Richard Gwinn Bowe Eulogy, by his brother, William J. Bowe, Jr.

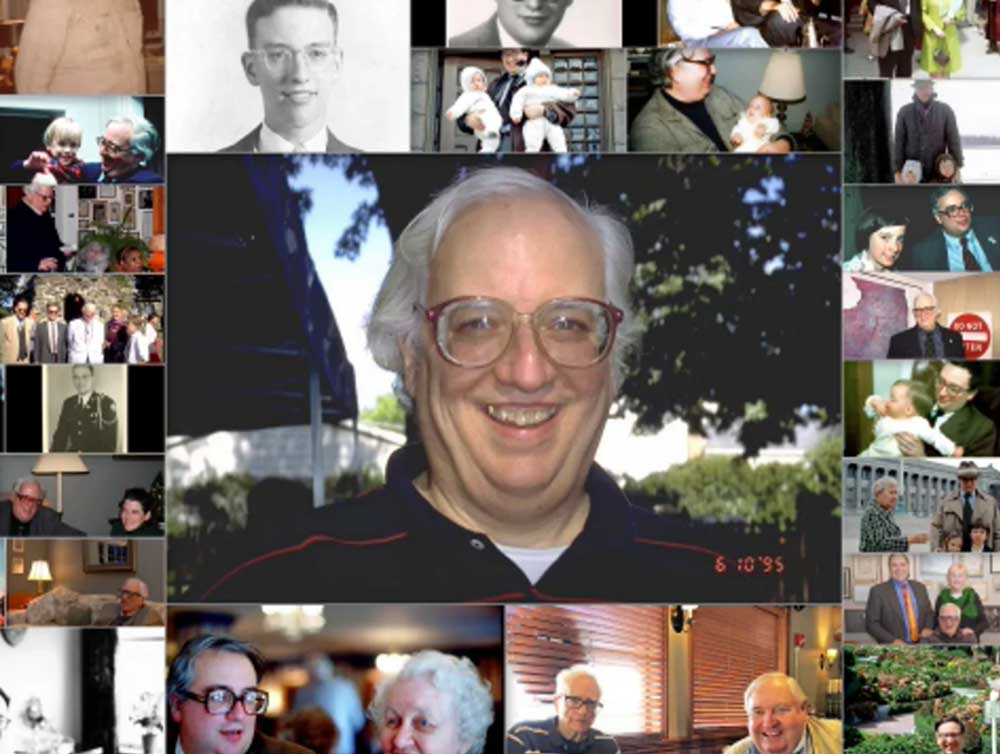

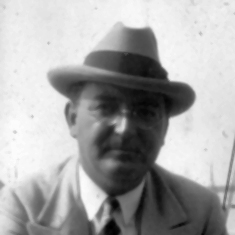

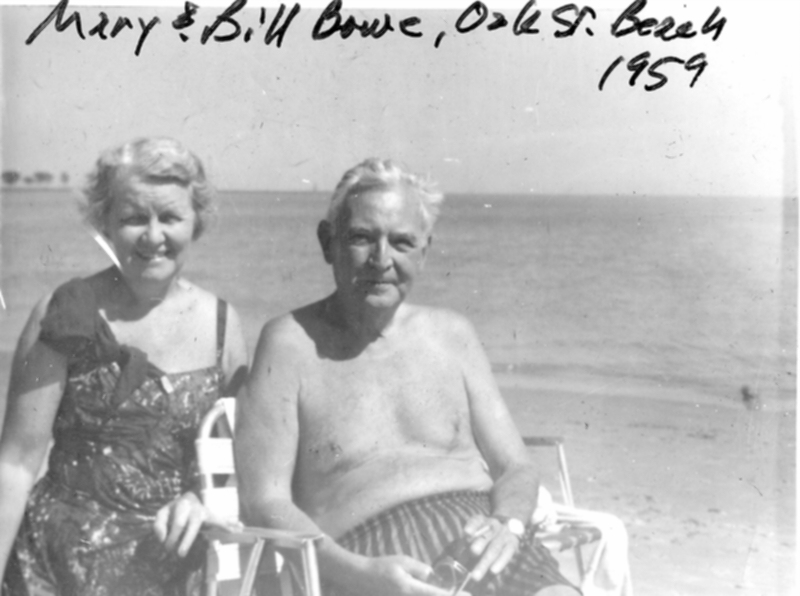

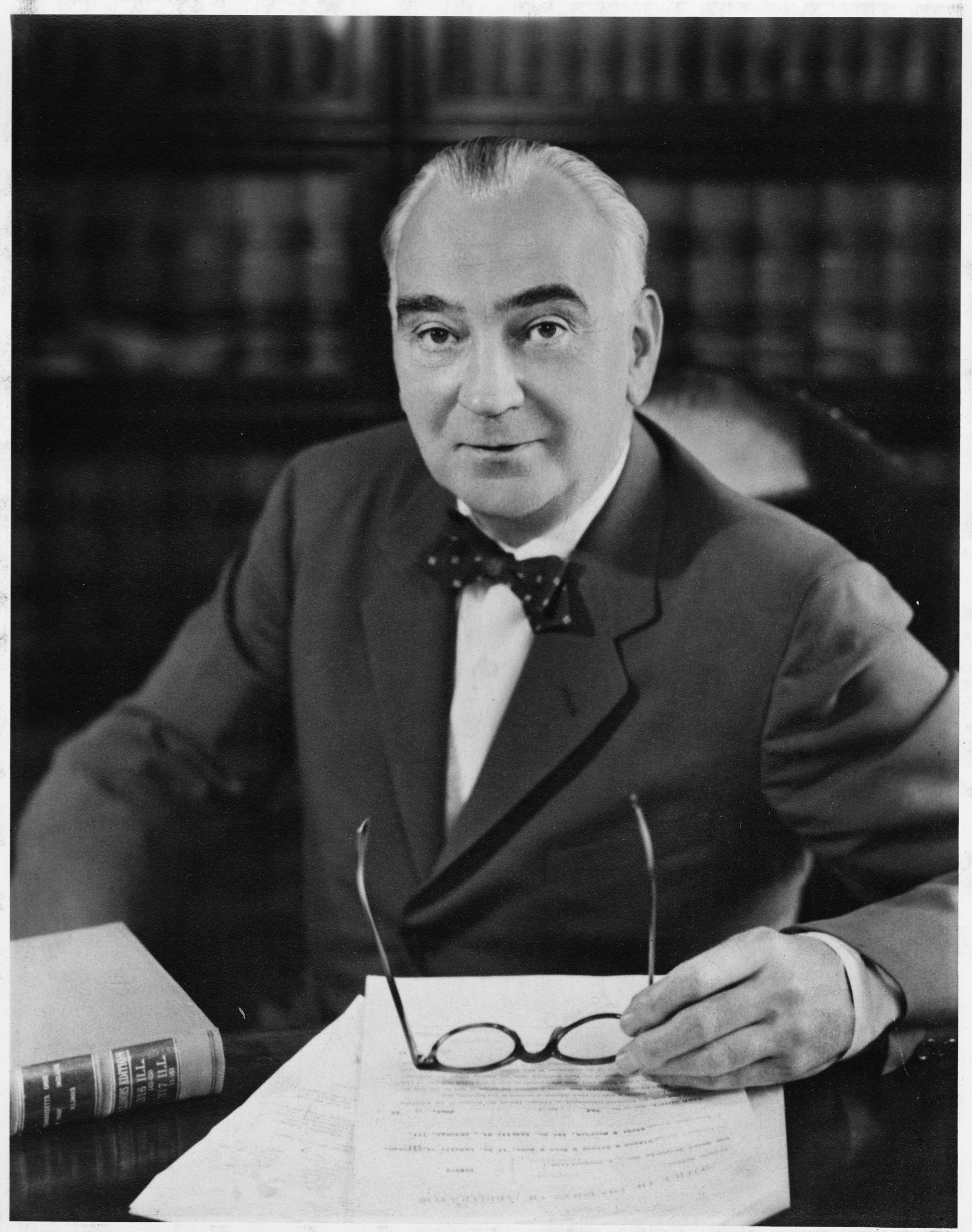

Richard Gwinn Bowe passed away peacefully on September 1. He was born June 22, 1938 in Chicago to William and Mary Gwinn Bowe. He is survived by his twin children, Alexandra Bowe DeRosa and Anson Bowe, his grandchildren Christopher and Charlotte DeRosa, his brother William, and his former spouse and mother of his children, Ann Fauble Mather. A later marriage to Greta Edwards ended in divorce.

After briefly attending Loyola University Chicago Law School, he joined the Illinois National Guard and worked in retail and as an office space real estate broker. He began his long career with the City of Chicago first working in the Human Relations Commission helping enforce the fair housing ordinance, and then in the Model Cities program dealing with police complaints. He last served as an assistant in the law department of its Board of Election Commissioners.

In retirement as in his working life, Richard was a voracious reader with broad interests in history, biography and Chicago.

Remarks of William J. Bowe

At the Memorial Lunch for His Brother Richard Gwinn Bowe (1938-2019)

The Cliff Dwellers

200 South Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL

Saturday, October 12, 2019

Welcome and Introduction

On behalf of Dick’s children, Anson Bowe and Alexandra Bowe DeRosa, I’d like to welcome you all to The Cliff Dwellers and thank you for coming to join in our farewell to their father and my brother.

Alex and her husband James have travelled here from Toledo with their children Christopher and Charlotte.

Anson joins us from the Upper Mississippi River where he works as a pilot on a tugboat named, “The Captain Bowe.” Not surprisingly, everyone calls him “Captain Bowe” and I’m impressed. In the Army, I was a lowly “Sergeant” and nobody called me “Sergeant Bowe.” Most people called me, “Hey, you!”

Notwithstanding the distance Alex and Anson and some of you have travelled, this is a convenient and fitting place to gather. Over the years, Dick and I often shared lunch here with family and friends.

Today, family and friends of Dick’s will again share a meal here and, in addition, again enjoy a wonderful view of Richard Bowe’s favorite body of water, Lake Michigan.

The plan now is to proceed with lunch. After lunch, those of you so inclined will have a chance to recall memories of Dick you’d like to share with all of us.

Feel free to make more than one trip to the buffet table. You can start with the salad and cold appetizers and then go back for the main course. And, don’t forget to leave room for dessert.

Dick, in his eating heyday, had a completely different approach to a buffet. He’d grab a plate, fill it with a bit of everything, including dessert, and then make repeated trips back for more. He knew it was time to stop eating only when it became hard for him to stand.

I’m not an expert in the human genome, but I believe Dick was afflicted with BED. For the ignorant amongst you, that’s short for Buffet Eating Disorder. I also believe that Dick’s BED was caused by a recessive gene in our Bowe Family’s DNA. I say this with some confidence because the only person I know besides Dick who used to eat like him at a buffet was his only brother.

Anson, would you please offer prayers for your father before we begin lunch.

Buffet Lunch

Eulogy – Bill Bowe

Shared Birthdays Our parents always had a joint birthday party for Dick and me. They explained to us that we were born four years apart on June 22nd. When I turned 16, and needed a birth certificate to procure my driver’s license, I was devastated to see I was actually born on June 23rd. It was a shock to realize that before then I’d been tricked into celebrating my birthday on Dick’s birthday.

Years later, after I became a parent myself, I told myself that when my parents rolled my birthday into Dick’s, they probably weren’t intentionally favoring the older son over the younger, nor did they really plot to perpetrate a natal fraud on moi, a vulnerable, innocent child of tender years.

I came to believe Bill and Mary Bowe were at heart good people who had probably conducted a careful cost benefit analysis and were simply pursuing sensible economies of scale. After all, one large birthday cake costs less than two slightly smaller ones.

I arrived at this forgiving insight when I once sought to save money by telling Andy and Pat that I was going to buy them a large bag of Little Louie’s French fries to share, not the usual two small bags. As I had been taught at their age, I explained that one large bag should be plenty for both of them, particularly, “…when children are starving in China!” In spite of the power of my logic, Andy flat out refused to share. Although I don’t remember exactly what Pat said, it was probably something like,

“Pops, don’t be mean, dude.”

I abandoned my plan when they told me that if I carried out my threat, they would report me to Cathy. Well, for my entire life Dick has remained four years older. Sadly, I finally have a chance to catch up.

Devotion to Family On a happier family note in Dick’s case, I think first of his devotion to his twins, Alex and Anson.

He and their mother Ann Mather, who joins us today, maintained a good relationship over the years. This helped Dick have a continuing presence in their lives as they grew into their adulthood. And this was notwithstanding the distance between Chicago and Toledo and the fact that Dick didn’t drive.

In recent years, as he dealt with bouts of rehabilitation from knee and heart surgeries, both of Dick’s children were concerned, as I was, about his continued insistence on living alone. Of great help to him was Anson’s and Stella Machado’s ability to step in to help him deal with his medical, travel and other issues of the day as he carried on the independent life he desired.

Humor Dick was blessed with an extraordinary sense of humor and he always enjoyed making people laugh. For instance, he knew he would get a laugh out of me by telling me with an almost straight face that the worst day of his life was the day I was brought home from the hospital.

I sometimes didn’t get the laugh when we were very young. One example brutally etched in my memory occurred when we were perhaps four and eight. At the time, we shared the same bedroom. After our parents turned out the lights, said goodnight and closed the door, Dick remained in his bed, and growled at me in the dark,

“I’m coming to get you now. I’m getting out of bed now. I’m crawling across the floor now. I’m going to fix your wagon now.”

Instead of screaming as I did, I wish I’d been as mature as Pat is now and simply said to Dick, “Bro, don’t be mean, dude.”

Well, that was all a long time ago and I’m not one to hold a grudge forever. I want you to know that last month, after only 73 years, I’ve decided to forgive him.

In later years, Dick grew to have at his command many different dialects, voices and impressions. They were all funny, accurate and impossible not to laugh at.

He carried this jovial bent throughout his entire life. When I recently talked to his wonderful caregiver at the end, Stella said that Dick and she were always laughing about something together. And this was notwithstanding the fact that at this point Dick was dealing with early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Chicago Besides Dick’s humor, I admired his love for Chicago, the city of his birth. I remember Dick as a teenager reading about the great architecture here and instructing me as to why we had the good fortune to live in such a wonderful city.

This devotion may help explain why Dick served as a dedicated employee of the City of Chicago for the greater part of his working life.

On the near West Side, close to where my father Bill, his brother Gus, and their sister Anna were born, there is a fountain at the triangular intersection of Division, Milwaukee and Ashland dedicated to author Nelson Algren. On it is inscribed a phrase from his prose poem Chicago: City on the Make. It reads,

“For the masses who do the city’s labor also keep the city’s heart.”

Dick in his labors as a City employee certainly helped “keep the city’s heart.” He did this in his work for the betterment of race relations at the Commission on Human Relations, in his work dealing with police complaints for the Model Cities Program in Uptown, and in his work at the Board of Election Commissioners helping to conduct fair elections.

A different Chicago author, doing background research for a novel, once interviewed Dick in his Model Cities office in Uptown. The result in part was a fictional character named George Duffy. A passage in the novel about Duffy, if not the rest of Duffy’s profile, surely describes Dick.

“… George knew Uptown like the back of his hand. Duffy roamed Uptown and made peace with problems…”

Sandy Bowe wrote me a nice note about Dick’s political acumen and care for others. Sandy said: “I respected Dick for his insight into city politics and his concern for the underprivileged.”

Dick was a committed political soldier ever since he started working for the City when Richard J. Daley’s was mayor. His political enthusiasm and loyalty could never have been in doubt. For instance, I was astounded to learn that he had offered to resign his position with the Board of Election Commissioners when he found out I was going to run as an independent Democrat against a Daley- endorsed candidate for 43rd Democratic Ward Committeeman.

With his enthusiasm for the political arena, it’s not surprising that he and his second wife Greta Edwards both enjoyed a deep immersion in neighborhood affairs during their time together.

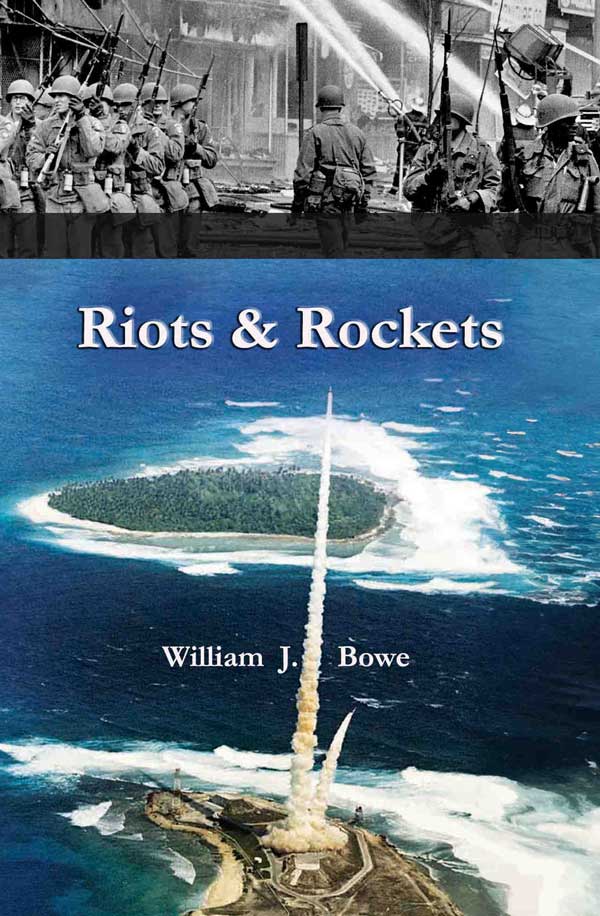

Books Beyond his work for the City, Dick had a deep interest not just in Chicago and its history, but in the history of our times. Born in a pre-digital era, he satisfied these interests through a lifelong consumption of historical novels, histories and biographies.

When Anson and I recently went through the many books filling the bookcases in his apartment, I was struck by the sheer range and volume of his reading.

One result of Dick’s reading is that no one ever got bored talking to him. Having consumed such an expansive array of facts over a lifetime, Dick was ready to rock and roll when the time called for it.

Walter Heffron touched on this when he recently emailed me to regret that health limitations prevented him from joining us. He recalled this conversation with Dick.

“I last talked with him at Kathy Bowe’s memorial. In our discussion about family, I happened to mention my father’s middle name was Salisbury, on which he expounded at length from his extensive knowledge.”

And Ann Heffron observed in a note to me:

“Dick was such a unique individual or a ‘character’ as Grandma Lynch used to say. He was quite the raconteur, and his political stories were most informative, and sometimes very amusing.”

On the other side of the coin, Tony Bowe made me laugh out loud when he wrote,

“I have many fond memories of fascinating conversations with him. He was ahead of his time: a conspiracy theorist before it became commonplace!”

The only two other family members I recall satisfying their intellectual curiosity by reading so extensively were my uncle Gus Bowe, my father’s brother, and my uncle John Casey, my mother’s brother-in-law and a cousin of my father’s. God rest these two literate souls, as well as Dick’s.

Reflecting on Dick’s penchant for reading, permit me to offer a final prayer. Please bow your heads.

“Dear Lord, if you can see your way clear, issue Dick a library card. Also Lord, while I’m thinking of it, please waive his late return fees – in perpetuity. Amen.”

Toast – Bill Bowe

Now, I’d like you to all join me by looking out at Dick’s favorite body of water and raising a glass in his memory. Our mother’s favorite toast celebrated HEW, the cabinet department created by President Eisenhower in 1953, boringly renamed in 1979 as the Department of Health and Human Services.

To our mother’s favorite HEW toast I have added a suffix to recognize Dick’s passing. “To Richard Bowe: And to his Health, Education and Welfare in the great beyond.”

Anson will now offer some thoughts about his dad, followed by his sister Alex, Stella Machado, and any of you who might wish to recall something of your own about Dick. Anson.

1968-09-05 RPT- Richard Bowe Human Relations Report on Lincoln and Grant Park Demonstrations

William John Bowe, Sr. Materials

1970 William John Bowe, Sr. – His Early Life & Law Practice, Recalled in The Families

Early Life and Schooling

In The Families, Mary Gwinn Bowe wrote about her husband’s early life:

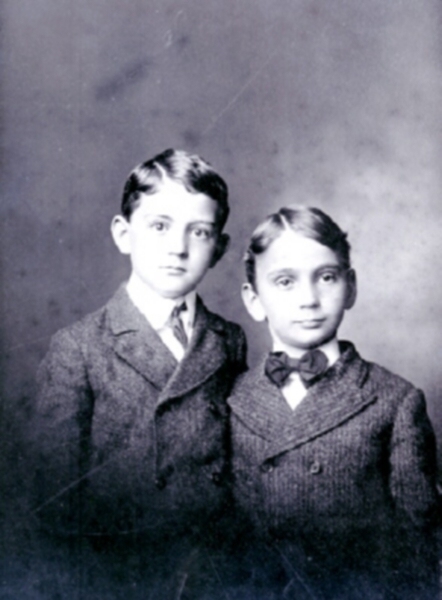

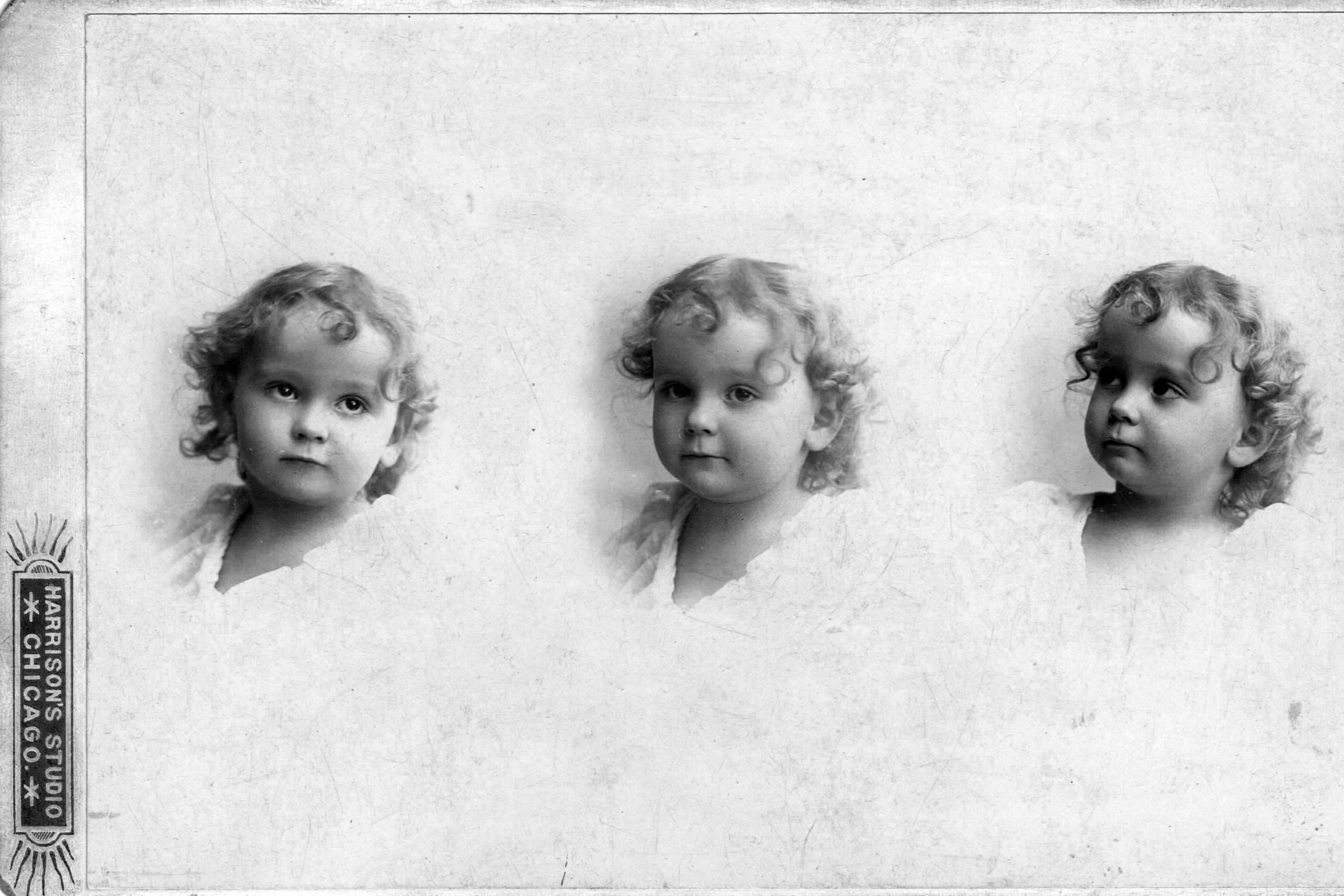

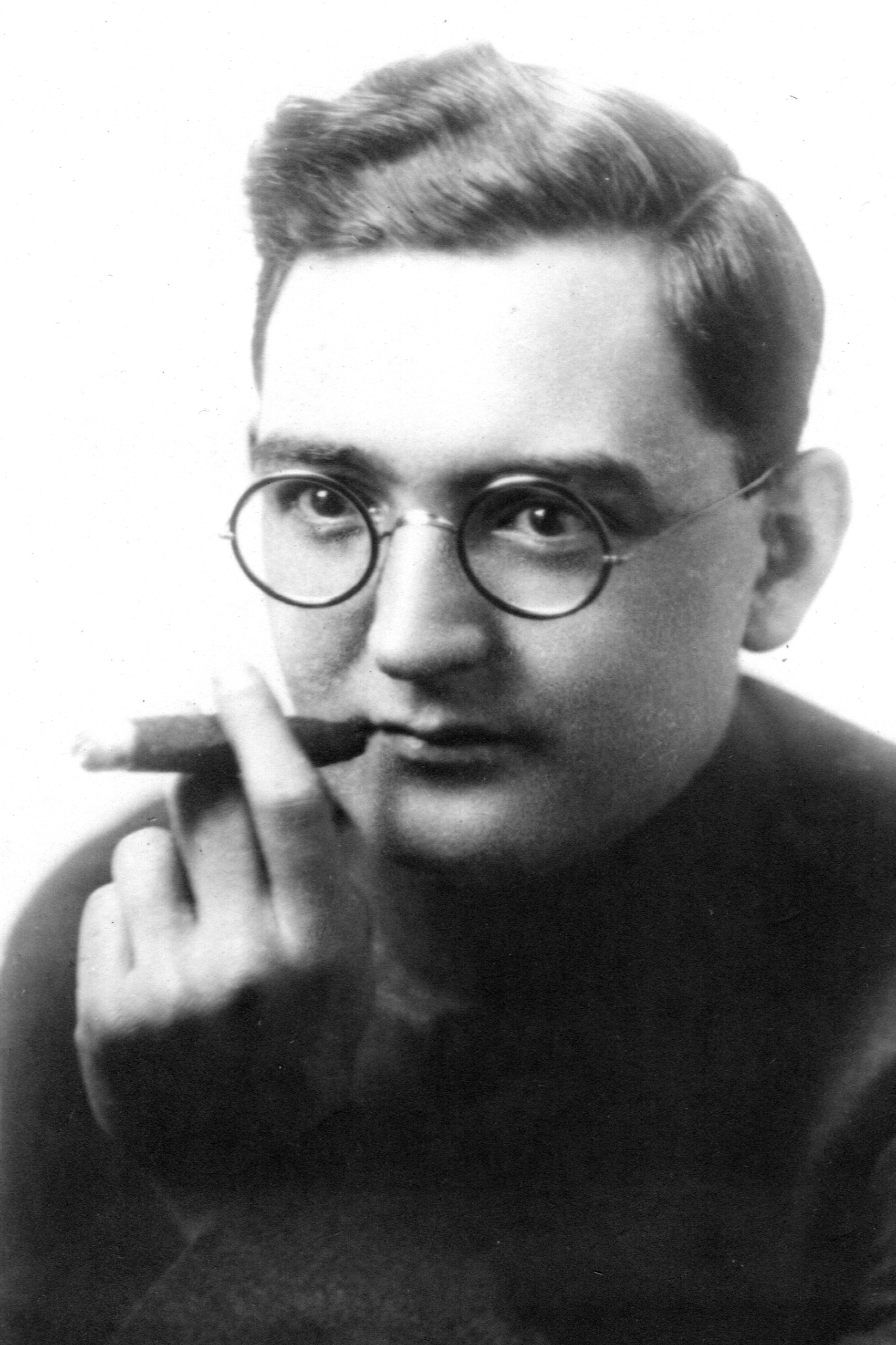

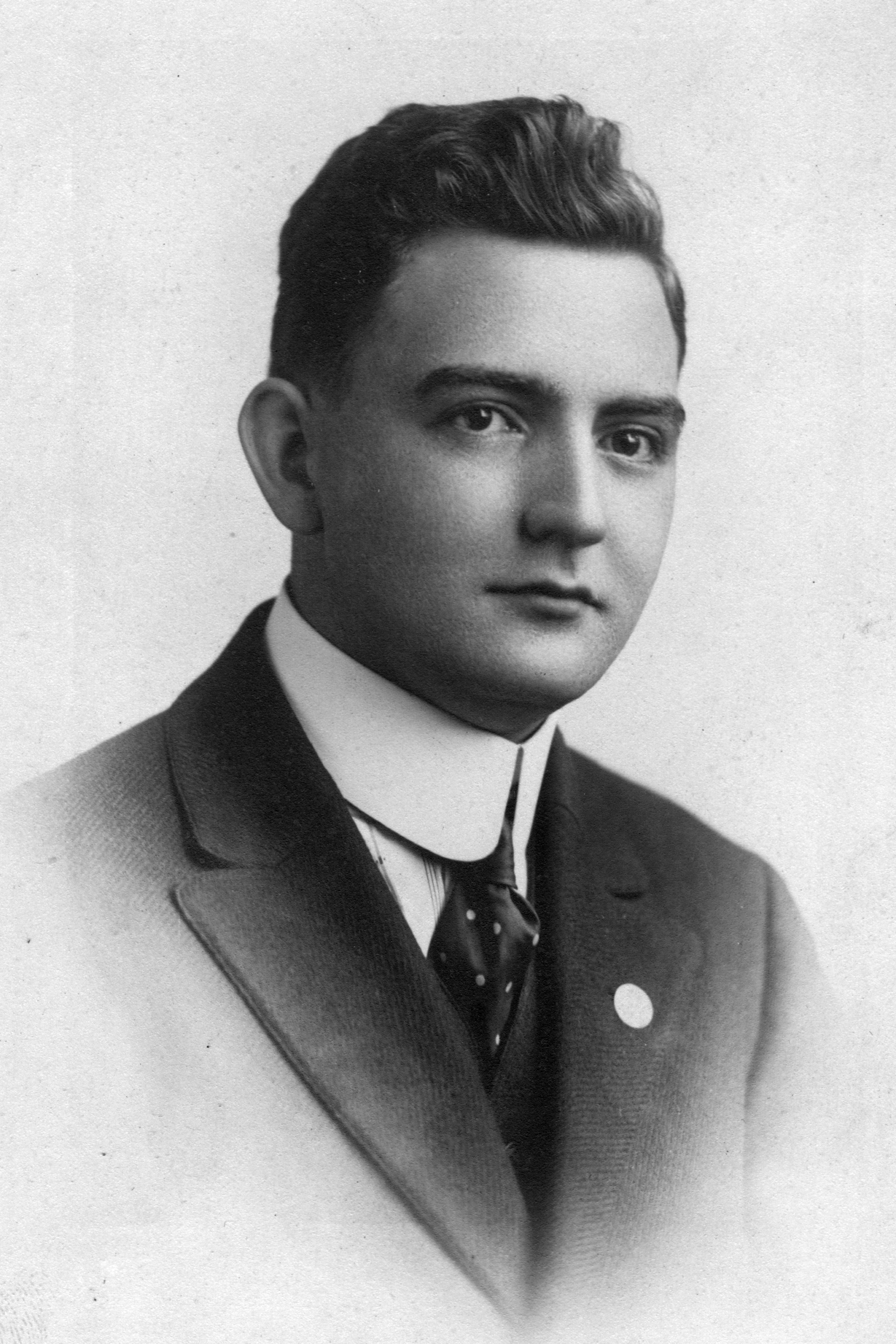

William John (Patrick) Bowe was born in Chicago at 1024 West Superior Street on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1893. He died December 30, 1965, at the age of seventy-two. I never heard him use or be called by his extra middle name Patrick. His mother was Ellen Frances Canavan. His father was John Joseph Bowe. He was a bright child, rather destructive, had all the infant diseases, loved animals and sports, and was well-liked and very sociable.

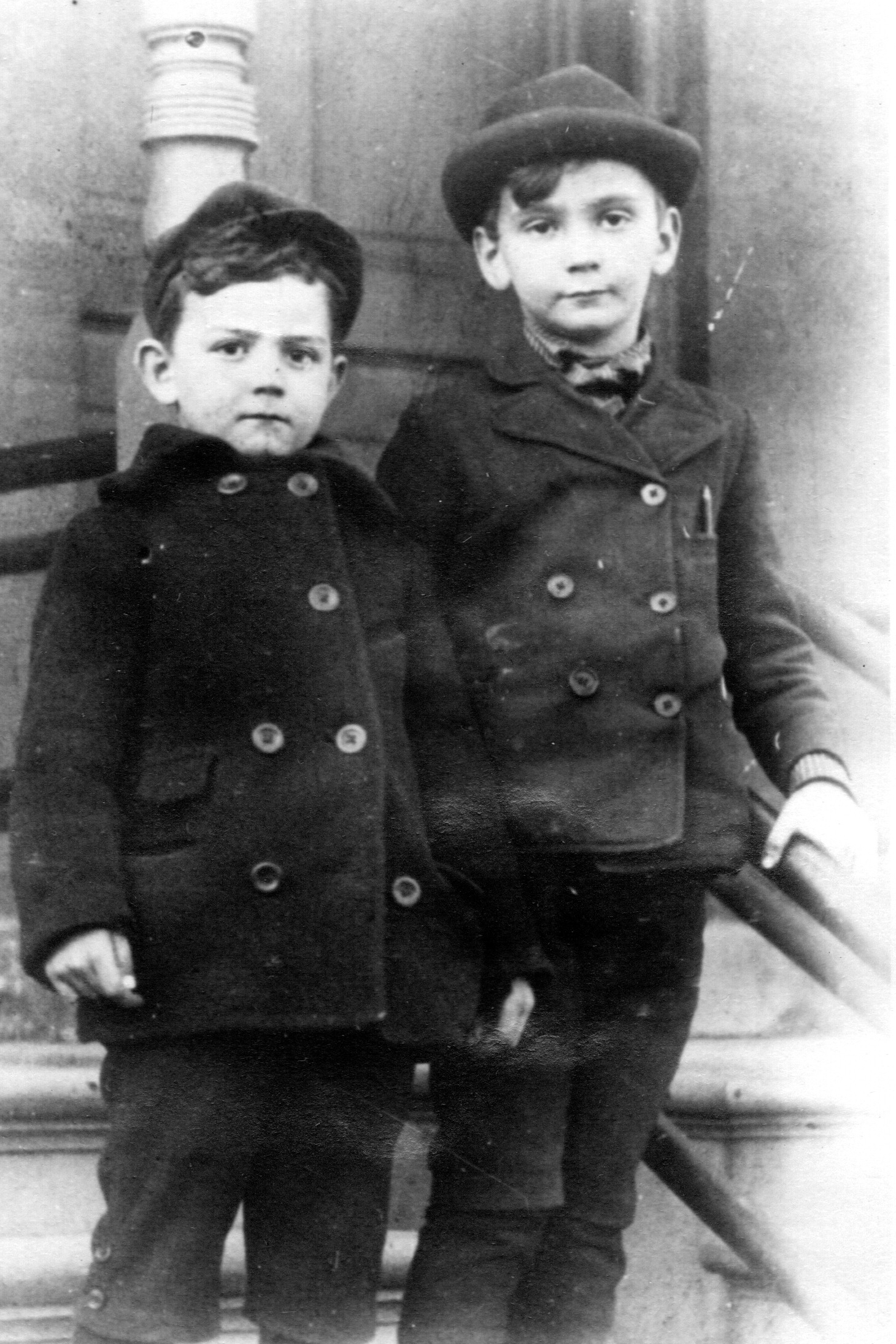

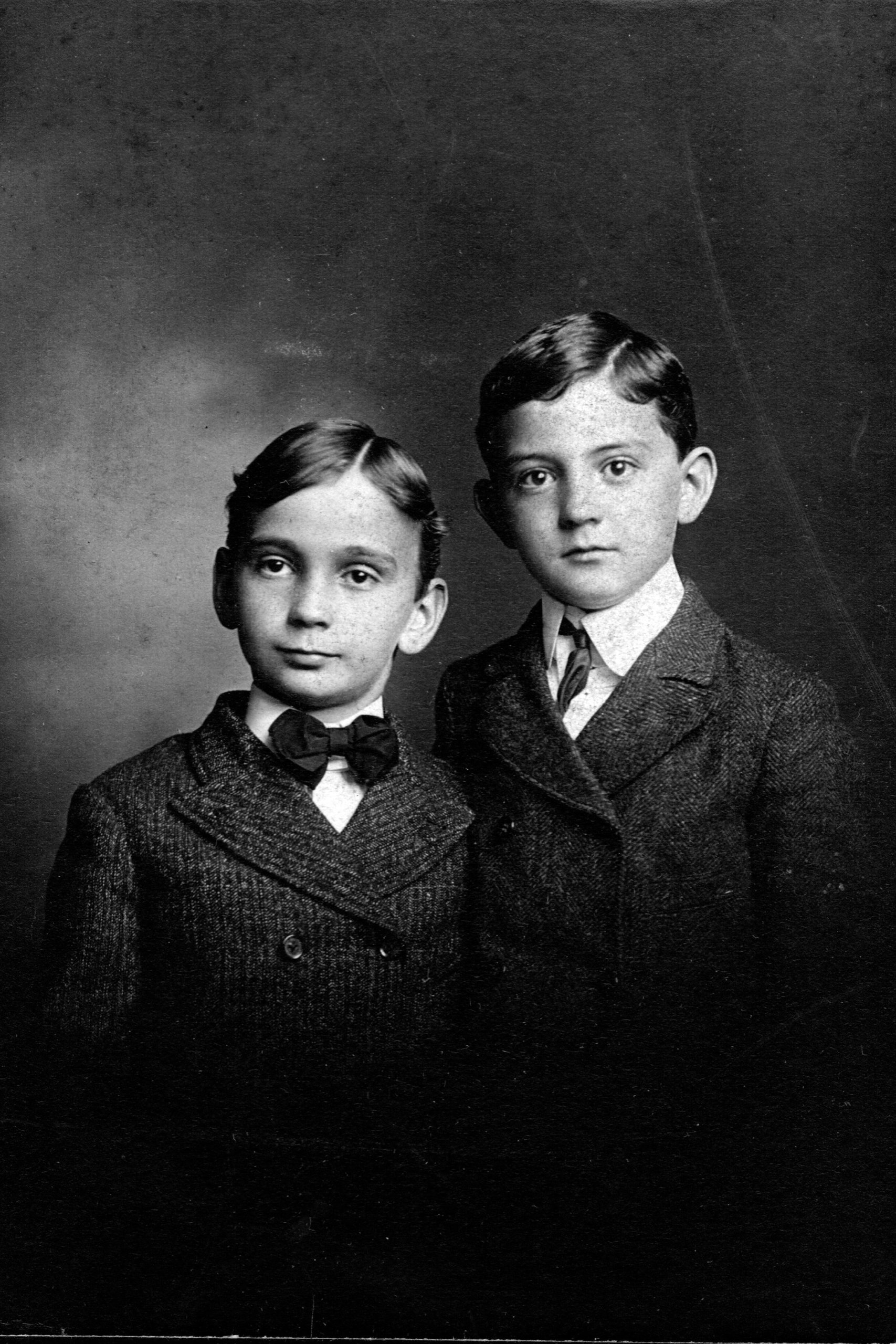

At four he went to kindergarten at the Alfred Tennyson School, fell immediately in love with the teacher and refused to stay unless she held his hand. He continued at the Fulton Street school until the sixth grade, when he went to St. Ignatius Academy at 12th Street and Roosevelt Road, where he remained until 1912. He made no particular scholastic history during this period and all honors in that line went to the scholarly Gus.

At eight he had a fearful bout with typhoid fever. A Sister Dismus nursed him and this illness affected his sight. He wore glasses from that time on.

In high school he was President of the Debating Society and was active in athletics. He finished in 1910. He also continued his college work at the same time he attended the Loyola University Law School. He received has law degree from Loyola in 1915. He passed the bar examination the same summer and became a lawyer at the age of twenty-one.

Helping His Mother Sell Life Insurance

When he was very small his sister Anna, the baby, was left in charge of the more reliable Gus, and Bill accompanied his mother Ellen as she sold insurance to other Irish families for the New York Life Insurance Company. She was very good at it. She took “Willie” with her on her evening calls, since most of her prospects worked all day. Bill said he used to listen to the conversations and hold his breath during those moments before the person signed up. Many of the fathers were in heavy or even dangerous work and their familites frequently had occasion to collect on their insurance. So “Aunt Ella” did a great favor to many unfortunate families as she taught them the value of insurance from her own life experience. In this way she supported her own family during the years of her husband’s illnesses and until the boys began their law practice.

Learning to Earn His Way in the World: Selling Books

Bill’s first contact in doing business for himself was in selling Bible Symbols to newly arrived young Irish girls. This is how he recalled that and other early business endeavors:

The idea was, ‘The Foxes Have Their Holes; the Birds of the Air Their Nests, but the Son of God Hath Not Where to Lay His Head,’ with pictures between every two nouns. The purpose of the books was to acquaint children with the Bible when they could understand pictures, but couldn’t read. It was a handsome volume selling for $3, with $1.20 being the agent’s commission. I was pretty successful that summer and actually made $300. I think every purchaser got fair value because it was a beautiful book. I remember one domestic, just arrived from Ireland and unmarried. She was about twenty and difficult to sell as she was illiterate and was also unable to understand the pictures. But she did gather that it was a book for children. I was proud of selling her the book because I told her that instead of a hope chest of vanities and fineries, her first purchase for the chest was this great gift for her children.

A 12-Year-Old Office Boy Democrat Rises to Editor of a Republican Weekly

When I was 12 or so, I answered an ad for an office boy. The salary was $3 a week. Seventy-five boys were lined up before the office opened at 127 North Dearborn Street, across from City Hall. This was also the same building the Bowe & Bowe law offices were later in. Mr. O’Grady, publisher of the Chicago Weekly Republican, quickly selected me for the job since I was pretty tall and wore glasses. The office consisted of a reception room and two small private rooms. Into the reception room he had crowded five desks which he rented to friends for $10 a month with the privilege of putting their names on the door if they paid for the gold leaf.

O’Grady got out his rewrite sheet only at election times. He was mostly busy soliciting ads and shakedowns from the Republican candidates. So the job of editor was soon handed over to me. He was the business manager, getting from $10 to $25 for promoting or not disparaging the candidates of the day.

I told him that I was a Democrat and, although not old enough to vote, I was entirely in sympathy with William Jennings Bryan who was running against William Howard Taft. I told him that I felt that I could not honestly edit a Republican paper. O’Grady said, ‘Will, what the hell do you think I am!’ So it was that he proceeded to instruct me in the duties of being an editor.

At that time Chicago had seven newspapers, all of them subscribed to by O’Grady. My job was to cut out anything bad about the Democrats and paste it on the format. Depending on how many ads or contributions he got, he would order them pasted in accordingly. Candidates who had their pictures printed would naturally subscribe for fifty or more copies for their constituents. In my time as the editor of this sheet, I tended to become more strongly Democratic.

O’Grady’s desks were rented out to a retired army officer who was working on a system of defense tactics far in advance of the atomic age, an alderman, and three others. Various people also had it as a mailing address.

The rent for the entire suite was $35 a month. Our publisher collected $50 from the lot and was sensible enough to have a pay telephone. O’Grady was about fifty when I knew him and had made many friends along the way. Some presumed upon his kindness and generosity to the extent that two dear old buddies slept on the floor when they were temporarily embarrassed, which was always. One was an old gambler with consistently bad luck. From him came my introduction to bookmakers. As an “editor,” I thought at first that bookmakers were publishers. He would put $2 in an envelope and have me take it to his bookmaker. This turned out to be the colored doorman at the Republic Theatre, who took care of all such printing.

That summer was very hot and it was before Grant Park was beautified. A wooden bridge spanned the Illinois Central tracks and led to the lake at Randolph Street. At night this charming old horseman would cross the bridge and walk a block or so to the water. There he had the whole lake to himself and, with no need for a suit, he would cool off his 275 pounds in Lake Michigan. Then he would return to sleep on the sofa at 127 South Dearborn.

Of all my friends of this period I loved the Kentucky gambler best, for his cleanliness, if not for his Godliness. More than once he retired to the closet while I took his brown suit out to be pressed. He and O’Grady finally had a fight and, in all heartlessness, O’Grady told this dear soul to get the hell out. Although election was coming near, on the departure of my friend I lost all interest in supporting William Howard Taft and I retired. O’Grady’s parting words to me were, “Never trust a Republican, especially one who’s a Democrat.” I finished the rest of the summer working on one of my uncle’s farms.

Summers on a Canavan Farm

In all I worked on the farm two summers as a boy without pay and two summers for pay. The first summer that I was paid, I received 50 cents a day and board. The next summer, nothing being said about a raise, I assumed it was more. On being told at the end of the season that there was no increase in salary, my indignation was so great that when Tennes Marcotte drove me six miles into town to take the train to Chicago and handed me $9 in silver for three weeks work, six days a week, I demanded more. The train was pulling in when he said, “Well, Bill, I’ll write you about that. You’ll miss the train.” I said, “We’ll settle it now. Seventy-five cents is my price.” He said $9 was all the money he had with him. I said he could get it in town and I’d wait for the next train. He pulled out the balance at once and I got aboard.

However, thinking back, I’ve always regretted my demands, remembering how much I ate, how tall I grew and how much I enjoyed that pleasant life that children today can only guess at.

The Mission Art Company

I had been selling one thing or another from the time I was ten. The next thing was the partnership Gus and I had in the Mission Art Company. It had offices in Chicago and a mythical one in St. Louis to make it appear to be a vast company. The main business for Gus and me was the sale of luminous crucifixes through door-to-door salesmanship. We had them made by a Mexican.

I copied the John A. Hertle system of selling by engaging high school and college students as agents during the summer. I copied their useful contract, substituting our Mission Art Company name and guaranteeing $16 a month. We also put ads in the employment columns of the Daily News guaranteeing $60 a month (the company agreeing to make up the deficit if the commissions did not amount to that sum). A born salesman and a genius could perhaps have made that much. Those who after a day or two found it not a congenial employment never stayed long enough to collect their guarantee so the Mission Art Company stayed solvent. And a $50 balance in the checking account was never completely exhausted.

I also followed the Hertle idea of recruiting at various schools, St. Ignatius College, Notre Dame University, wherever students were looking for summer jobs. And many of them were really successful and I’m sure they look back on those experiences as giving them valuable training in meeting the public and learning salesmanship.

Teams were sent to various places. For several days I would stay and work with each showing how easy it was to sell the luminous crucifix. A crew of seven was established in the very Irish and Catholic city of Joliet. We rented a large sample room in a small centrally located hotel. The rent was a $1.50 a day, but for an extra 50 cents they put in seven cots, making it all quite reasonable.

We were all young men with voracious appetites and we solved the eating problem in the first couple of days in a Chinese Restaurant next door that had amazingly generous portions of Chop Suey, together with tea. It was all you could eat for 25 cents. The first several days we had Chop Suey for breakfast, lunch and dinner. My college boys were all attractive, as college boys always are, and they used the sales talk in which I had trained them, that they were “working their way through college.” Based on the Catholic parishes Christmas contributor’s list, I sent them only to selected sections of the city where the price of a $1.50 would not be considered prohibitive.

It was not long, perhaps four days, before each young man had made social contacts through which all of the crew were invited to homes of affluence, often including not only dancing in the converted attic ballrooms, but sumptuous suppers. When the seven of us stormed in we met with some resentment from the local boys, but women are fickle and the Chicago college team was momentarily more attractive than the natives. When my friends were comfortably established among the Four Hundred and could count on ham and potato salad as well as dancing, I myself moved on to another city.

Next I took a number of students down to Belvidere. In Peoria I appointed a resident representative. At the end of the summer I returned to school, but we realized that in a volume business it was impractical to rely on summer students. So Gus and I went into the manufacturing end.

In those days people hung portraits of their relatives in the living room. There was a company that made portraits from small pictures and although it was on the wane, they had a fine sales organization in Chicago with a great many agents.

Now we sold wholesale. We got a small picture frame factory and a portrait enlargement concern wiring to take on our line: luminous crucifixes, statuary and religious pictures from which the Sacred Heart of Jesus would send out inspiring rays during the night — “To The Cross I Cling.” We even had a couple of connections in South America. Finally and sadly, in a large order for Mexico, all the statues of the Sacred Heart stuck together due to the tropical heat. This put us out of business and closed my commercial career. I was 19.

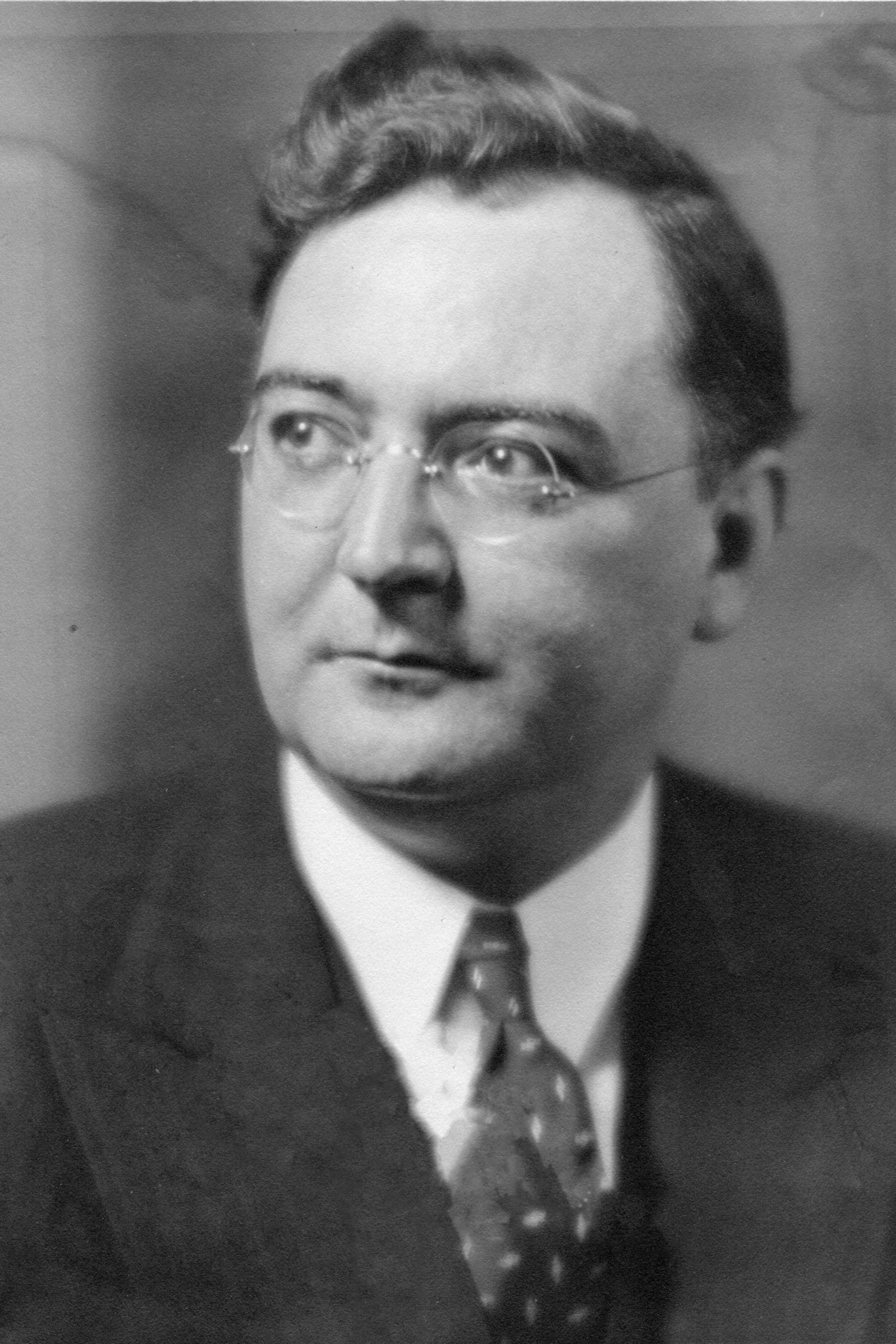

Early Lawyering with Gus

Gus passed the Bar examination in 1913 at the age of 21 after a distinguished career as a student, having received his college A.B. degree at the age of 18. His notice that he had passed the Bar came in July. The Supreme Court had an October term so, as a businessman, I saw a great financial loss between July and October when the Court would sign the license to practice. I had great faith in Gus and felt that he should be able to start his practice immediately and not deprive people who needed him of his services. I felt it was incumbent upon me to get him some clients.

A few days later, about the end of that July, I read in the paper that a sudden windstorm had caused injuries to some patrons of the Gentry Brothers Circus then showing on the South Side. Names and addresses of a dozen or so were given. None were seriously injured unfortunately. But the lights had gone out, panic had developed, and some had incurred rope burns. Others had sprained their ankles. I quickly called on all of the victims whose names were published. They were much cheered by my interest in their misfortune. I was much depressed that it was not more serious.

I gathered up seven or eight Powers of Attorney, appointing Augustine J. Bowe their lawyer to collect damages for the catastrophe. An attorney’s lien law recently passed by the Illinois Legislature provided that the attorney’s interest in the outcome of the claim would be one third of the proceeds. I served such liens on Mr. Gentry. He at once offered me settlements, ranging from $50 to $75 in each case. We had later friendly dealings with him and on one occasion were offered a baby elephant as part of a settlement.

After the Gentry affair, Mr. Schultz came along. He was a passenger on a streetcar which collided with a horse-drawn truck. Unfortunately for me, he too was not seriously injured. The streetcar company refused to settle, holding that the horses of the Dunn Coal Company became unmanageable and jumped in front of the street car . We sued them.

It was the first case Gus ever tried in court. A non-jury case, it was tried before Judge LaBuy, a brother of Judge Walter LaBuy. He assessed damages of $350 and we got our first fee of over $100.00.

Sometime later I was alerted to the death of a seven-year-old boy whose mother was a widow living near the Stock Yards. Somehow this little fellow got down to 24th and Dearborn. In an alley behind the old Standard Club, at that time at 24th and Michigan, a Consumers’ Ice truck delivering ice to the Club, backed up and killed him. The mother with her two other children was receiving $2 a week from the United Charities.

So I told Mrs. Greaves, as one Irishman to another, that I would gladly represent her. I mentioned my cousin, Dr. Thomas Hughes, who had practiced in her neighborhood for 40 years. She knew him well since he had delivered her three babies without charge. She felt sure he would want me to look after her interests.

At that time the courts of Cook County were so far behind that it took three years for a case to reach trial. We learned that the Consumers operated also in Lake County. So we at once filed suit in Waukegan, the county seat, and got service on one of the trucks there. In three months the case came to trial with a verdict returned of $5,000. At the time, that was double any judgment ever returned for the death of a child of that age. My old friend, Ernie Stout, made a two column story for the Chicago Evening Post, “Chicago Lawyer Finds Way to Defeat Law’s Delay.” That publicity paid off later in many other cases.

In World War I Bill Loses Part of a Foot in a Troop Train Accident in France

The war interrupted and Bill enlisted and went off. Gus was left to take care of mother, sister and the law practice. Then Bill was injured in a train accident in France early in his military service.

The masthead of The Chicago Citizen on Friday, June 28, 1918 read, “The Only Irish National Secular Newspaper West of New York — Devoted to the Unity and the Elevation of the Irish People.” The headline read, “Chicago Man Injured at Front — Well Known Chicago Attorney Whose Bravery Sheds Luster on the Irish Race.” And the article took it from there:

“Sergeant William J. Bowe, who was injured in France in a railroad accident, but now on the road to recovery, is at present in the American hospital in Blois. Mr. Bowe was a Chicago attorney, a member of the firm of Bowe & Bowe, 127 North Dearborn Street, a member of the Knights of Columbus, the Chicago Bar Association, the A.O.H. Irish Fellowship Club, and Treasurer of the Loyola University Alumni Association. He was associated for several years in the practice of the law with his brother, Augustine J. Bowe, who is now carrying on the business of the firm. Their practice in personal injury and workmen’s compensation claims is very wide. Mr. Bowe is of Irish descent. His people hail from County Carlow.”

1918 saw Bill’s return with half a foot after a year in French hospitals. He was the first American to be cared for in Orleans and Blois. He never got over his love for the French because of their devotion and friendship during that year. In the days before antibiotics, he refused to permit the amputation of his leg and claimed that its healing could be attributed to “Dakin’s Solution.”

His third and last hospital at Savanay he found less endearing, but he was on his way home then, as it turned out. Then he was sent to Camp Dodge in Iowa, from which he was able to visit the Iowa cousins, the Harts and the McNulty s.

In spite of his lack of knowledge of the language of France, he returned annually and was always happily at home there. Indeed, France became the vacation objective of the whole family.

The Workmen’s Compensation Practice in Illinois

The Illinois Industrial Commission had been set up as early as 1913. It’s purpose was to handle cases involving hazardous employment. In 1911, Dr. Alice Hamilton had made a study of the white lead industry in the United States. The publication of her findings hastened legislation to improve working conditions not only among lead workers everywhere, but also to alleviate the abominable dangers in the coal mines of Southern Illinois and the East. This field of law was new and it proved a profitable one as the number of Workmen’s Compensation cases increased in Illinois and around the country.

By this time Bill had made many good friends at the Commission, now in the State of Illinois Building, and he took care of the personal injury and occupational disease cases such as silicosis and asbestosis before the Commission. Gus tried the jury cases in the Illinois civil courts. Captain Albert V. Becker was Chairman of the Industrial Commission for many years. He and Bill had served in the same unit in the National Guard, of which General Abel Davis was Commander.

:

Mary Gwinn Bowe Materials

1970 The Families, by Mary Gwinn Bowe

1970 Mary Gwinn Bowe Before & After Chicago, from The Families

1960-09-16 Mary Bowe Hosts Kennedy Kin in 1960 Presidential Election (Chicago Triboune

Julia Lecour Bowe Materials

2012-09-12 Transmittal of Julia and Gus to the Poetry Foundation (by William John Bowe, Jr.)

2011 Preface to Julia & Gus, by William John Bowe, Jr.

2011 Julia & Gus Acknowledgements, Charles Augustine Bowe

2011 Julia & Gus, Memoirs of Julia Lecour Bowe (Table of Contents links)

1994-03-01 History of the Lynch & Casey Families by Patricia Lynch Heffron

1986-11-16 Julia Bowe, A Savior of Poetry Magazine (Chicago Tribune Obituary)

1971-12-03 Invitation of Julia Bowe and Others to W.H. Auden Program of Modern Poetry Association

1970 The Families by Mary Gwinn Bowe (Table of Contents Links)

1967-07-24 Illinois Governor Otto Kerner Appoints Julia Bowe to the Illinois Arts Council

1960 Magic World of Yesterday, Mrs. Augustine Bowe Spins a Bedtime Tale for Her Grandchildren (Chicago’s American Article with Photo)

1959 The Generations, Julia Lecour Bowe (Table of Contents links)

Augustine Joseph Bowe Materials

On February 11, 1961 in City Hall Augustine J. Bowe is congratulated by Mayor Richard J. Daley and Richard Nelson as he is inaugurated as Chief Justice of the Municipal Court

Sen Paul Douglas (D. IL), Augustine J. Bowe & Gov. Adlai Stevenson

Gus, John, Julia and Julie Ann Bowe

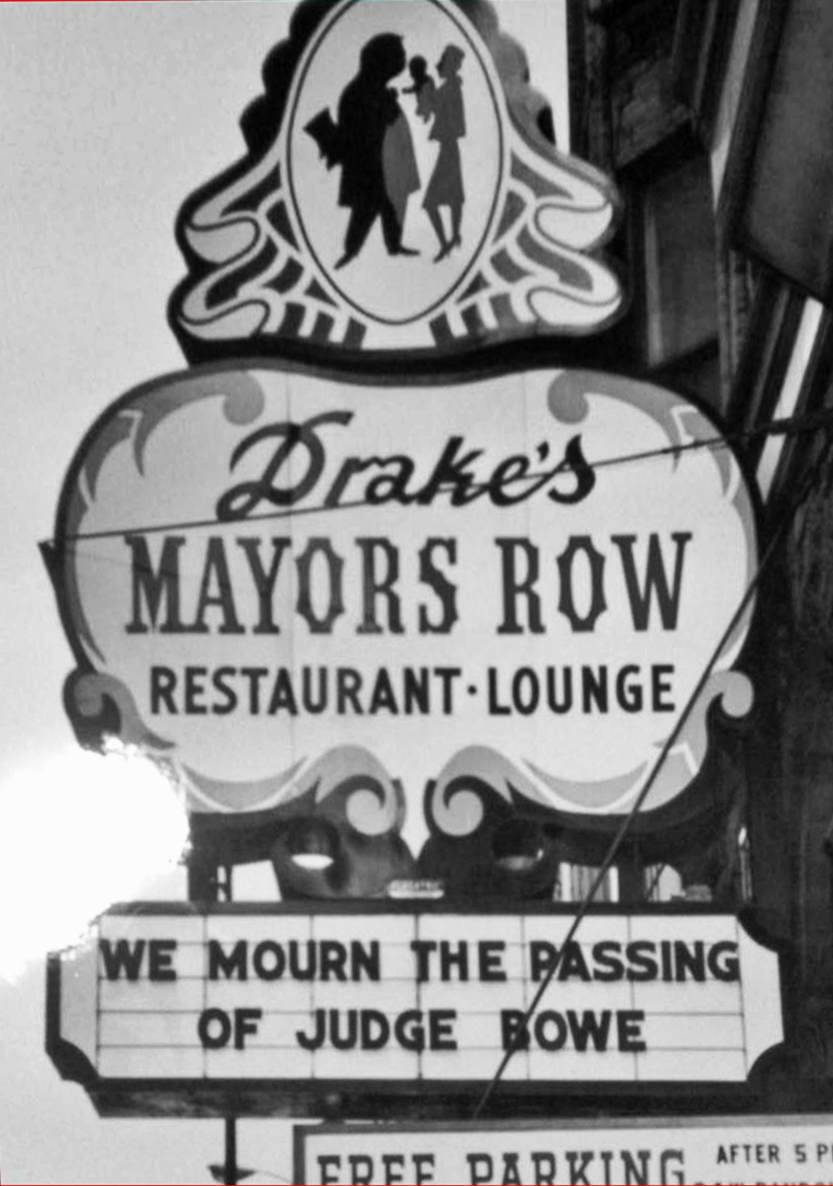

1966 Augustine J. Bowe remembered by the restaurant in the 1892 Unity Building at 127 North Dearborn Street. Bowe & Bowe had their law offices there from the 1910s to the 1950s.

2021-04-01 Honesty in Kindness, The Poet, Presiding Judge Augustine J. Bowe, revised and reformatted 2021 Chicago Lawyer article by Justice Michael B. Hyman (with picture of Judge Bowe substituted for the author’s)

2021-04-01 Honesty in Kindness, The Poet, Presiding Judge Augustine J. Bowe, original article by Justice Michael B. Hyman published in the April-May 2021 issue of Chicago Lawyer

2019-06-01 Augustine J. Bowe in Law School Course James R. Elkins, Retired Law Professor, West Virginia University

2012-09-12 Transmittal of Julia and Gus to the Poetry Foundation (by William John Bowe, Jr.)

2011 Preface to Julia & Gus, by William John Bowe, Jr.

2011 Julia & Gus Acknowledgements, Charles Augustine Bowe

2011 Julia & Gus, Memoirs of Julia Lecour Bowe (Table of Contents links)

2011-12-01 Profile of Judge George Leighton – Friend & Pallbearer of Augustine J Bowe (Chicago Lawyer Article)

2011-01-08 Augustine Bowe Archive Index (Newberry Library)

1995-07-01 The Demolition of Louis Sullivan’s 1892 Garrick Theater (Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society)

1994-03-01 History of the Canavan, Lynch, Casey, Gwinn & Bowe Families by Patricia Lynch Heffron

1975-05-01 Chicago Commission on Human Relations Newsletter

1970-12-31 A Note on the Brothers Bowe from The Families, by Mary Gwinn Bowe

1970 The Families by Mary Gwinn Bowe (Table of Contents Links)

1967-05-21 Augustine Bowe Poet (by Frederick Nims in the Chicago Tribune Magazine)

1966-02-06 Augustine J Bowe Mass Card with Teilhard de Chardin and His Own Poems

1966 Augustine J. Bowe Obituaries: Poetry Journal Co-Founder, Civic Leader, Dead — A Judge Who Spoke His Mind (NY Times & Mike Royko in the Chicago Daily News)

1966-02-07 “Judge Bowe Dies at 73” and “Judge Bowe, 73, Dies During a Walk” (Chicago Tribune Articles with Pictures, Page 1)

1965-12-30 Letters of Condolence to Augustine J Bowe on his brother William J. Bowe, Sr.’s Death (from Mayor Daley and 5th Ward Ald. Leon Depres)

1965-12-25 Judge Augustine J Bowe and Julia Bowe Christmas Card

1965-10-04 Six Women Judges (Chicago Daily News (Augustine Bowe Quoted)

1965-08-02 Judge Augustine J Bowe Opens Civic Center Courts after Move (Chicago Daily News)

1958-02-23 Augustine Bowe – Chairman Chicago Commission on Human Relations (Chicago Sun Times Picture)

1957-06-25 Congressman Sydney Yates writes to Gus and Julia Bowe (after Chicago’s American Newspaper Profile)

1957-06-14 Frank Stenson to Gus and Julia Bowe (after Chicago American Profile Article)

1957-06-13 Mayor Richard Daley to Gus Bowe after Chicago American Profile Article

1957-06-12 Julia and Gus Bowe Profiled in Hearst Newspaper Chicago’s American

1954-08-13 Augustine J Bowe Leads Panel on School Desegregation of Loyola Law School

1952-1927 A Typical Illinois Supreme Court Case Argued by Bowe & Bowe

1947-01-01 Augustine J Bowe and Catholic Interracial Council (Edward Marciniak Article – Opportunity Vols. 25-27)