The Riboud Family during World War II

Editor’s Note: In November 2023, I had a chance to talk with the Riboud cousin closest to me in age, Olivia “Livie” Riboud. Livie is the daughter of my mother’s sister, Nancy Gwinn Riboud. When I spoke with her on Zoom, Livie was in her Paris apartment on Avenue Raymond Poincaré and I was in my home office in Northbrook, Illinois. At the outset of World War II, Livie’s father Jacques Riboud had fought a losing battle against German tanks as an officer of a French horse-drawn artillery unit. I was familiar with his wartime experience having edited and written the preface to his the English language account The Horse War (in French Souvenirs d’une Bataille Perdue). In this conversation, I was anxious talk to Livie about her mother’s experiences in her perilous travel with her three daughters out of German-occupied France early in the War. Our mutual goal in recording these memories is to foster a continuation of today’s strong trans-Atlantic bonds with later generations of the Gwinn, Riboud, Lacombe, Kuhn, Corderoc’h, Bowe, and Casey families.

Subtitles of my interview with Livie are available in both English and French. Simply choose one of the closed captions available at the CC icon of the toolbar under the video. Also, if you click on the grid icon to the right of the CC icon, up will pop up the a list of the interview’s chapters. Clicking on these chapter headings permits you to jump around the interview at will to parts you find of interest. You’ll find further details on the subjects covered by Livie in these chapter summaries below.

Chapter 1. I began by asking Livie about problems arising from the failure of a proposal to add three floors to her apartment building. Next we turned our attention to the status of the Riboud family when World War II began after Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939.

Chapter 2. Livie reports that given she was in her infancy, what she later learned of this period came from direct conversations with her mother. She says that she had made careful notes of these family experiences her mother confided in her, only to later lose them. Thus, she can only consult her memories of these wartime stories, not the detailed notes that once existed.

Chapter 3. Livie explains that after her mother’s marriage to Jacques Riboud in 1933, and the birth of her older sisters Chesley and Betsy, when she was born in

November 1939, her mother was being helped in caring for her three daughters by a Swiss nanny, Fraulein Busch. She credits the nanny for seeing Chesley through a dangerous earlier period of childhood anorexia. She also recalls later learning of the near asphyxiation of her and her siblings due to a broken coal-burning room heater during the winter 0f 1940, when they were living on the Rue de la Pompe in Paris.

Chapter 4. In the first family travel brought about by the German occupation of the northern part of France in 1940, Livie discusses the travel of her mother, the three daughters and the nanny to the house of her grandparents in Chindrieux. She goes on to describe the large extended family group filling the house to overflowing, and the presence in Chindrieux of Aunts Yvonne, and Nicole.

Chapter 5. With the Chindrieux house too crowded for a long stay, Livie described how Nancy attempted to take up the offer of a Paris acquaintance, the mother of Giscard d’Estaing, later French President. She had offered to let them stay at their chateau in Auvergne, France if circumstances required. With many days on the road with other refugees, and limited gasoline, the hoped for move to Auvergne became impossible and Nancy and the children retreated to Chindrieux.

Giscard d’Estaing Family Home, Auvergne, France

Chapter 6. With the first attempt to leave occupied France failing, Nancy and the children left Chindrieux and returned to Paris later in 1941. With the situation deteriorating under the German occupation, particularly for Jews, Nancy, who had retained her American citizenship when she married Jacques, had a friend in Paris who helped her work on getting the necessary travel papers to leave occupied France for refuge in a non-occupied part of France. However, Fraulein Busch being Swiss, was unable to accompany the family and returned to Switzerland.

Chapter 7. Later, Nancy and the children left Paris headed to Portugal on a Red Cross train with other refugees fleeing wartime France. At the border crossing with Spain, all the passengers had to disembark and transfer to a train with the proper gauge for the Spanish railroads. Also at the border, the passengers had to submit to a personal frisking. Livie reports that with mother next for being frisked, her mother briefly handed her to a German officer. Livie says that between her yelling and her personal and unexpected befouling of the officer, the officer quickly handed her back to her mother. With Nancy escaping the frisking, they finally boarded the train headed to Portugal.

Chapter 8. Livie says that her mother’s tale of the train ride in Spain was noteworthy for the lack of anything to eat, though in neutral Portugal there was plenty of food. She says she was given port wine there and plenty of bananas and that this later led to family jokes of her being a lush in infanthood.

Chapter 9. Holed up with other war refugees in a Sintra, Portugal hotel, Livie says her mother became deathly ill for weeks with double pneumonia and, though there was sulfamides, she was in desperate need for hard to come by penicillin. She says that with her mother incapacitated, a young Jewish girl, also seeking to leave Portugal by boat, stepped forward and was critical in caring for the three girls. As it turned out, a young and attractive American mercenary aircraft instructor normally training Spanish pilot to fly was vacationing at the hotel. When he saw Nancy, a fellow American in bad straits, he was able to use his connections with the German Army to acquire the penicillin Nancy needed.

SS Excalibur in New York Harbor

Chapter 10. In succeeding weeks, Nancy slowly recovered from her illness, and at the same time Jacques, who was working in Paris still, was able to obtain the necessary travel papers thanks to his friend Robert Lavoir and thus was able to join his wife and children in Portugal.

Chapter 11. With the family finally reunited, Jacques, Nancy, Chesley, Betsy, and Livie boarded the SS Excalibur in Lisbon, Portugal and sailed for New York. The ship had originally been launched in 1930 to carry tourists on Mediterranean cruises. In 1940, it had begun to ply the Lisbon-New York route. Besides the Riboud family in this period, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor also boarded the SS Excalibur in Lisbon as they were being evacuated from the European war theater. In their case, special arrangements had been made for the ship to call into Bermuda for the Royal couple to disembark there.

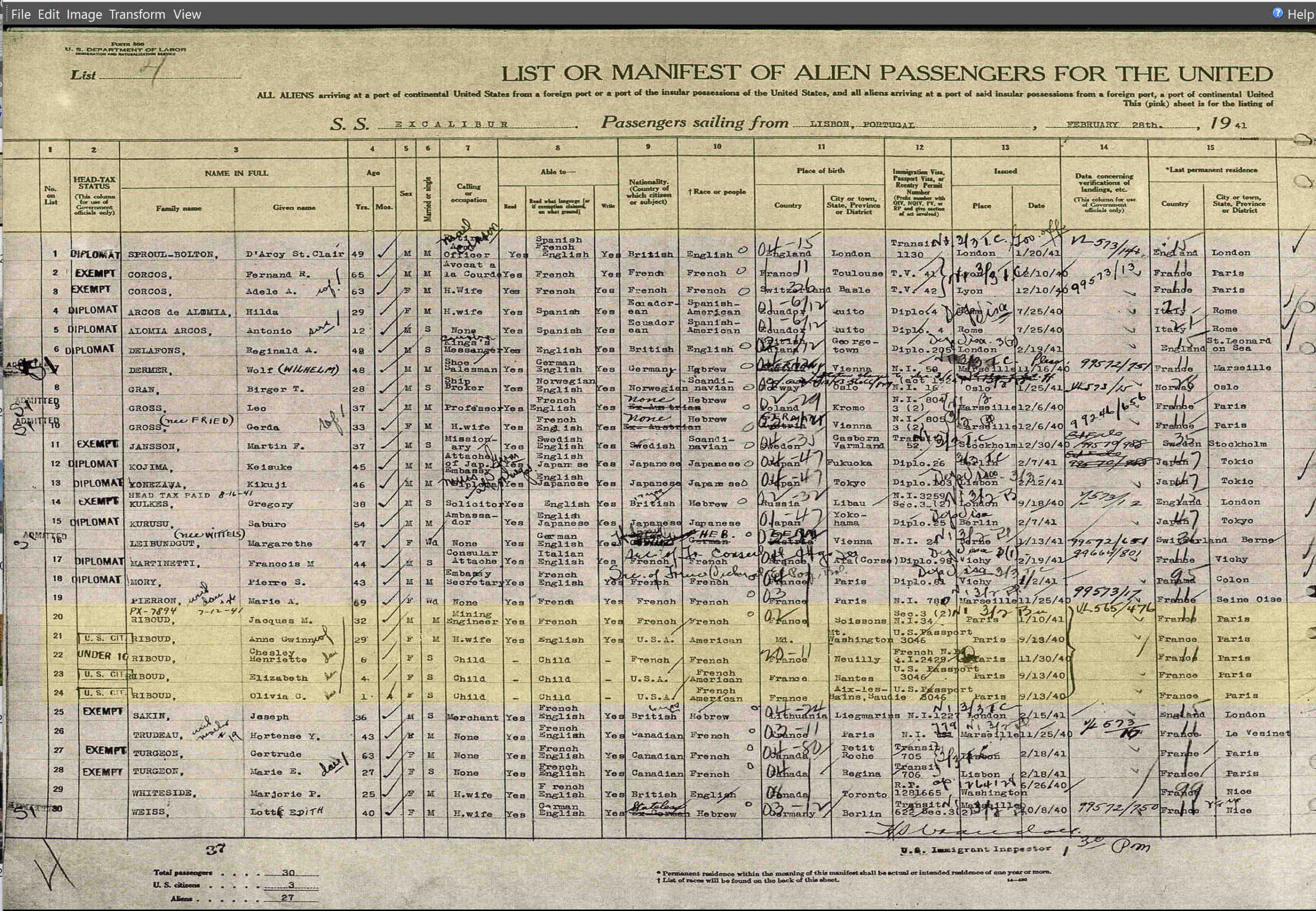

February 28, 1941, The Riboud Family Arrives at Ellis Island

During the Riboud family’s wartime years in the United States, they lived for a year in Elmira, New York, where Jacques was consulting with the Canadian Army on his ideas for improvements in the design of mobile artillery pieces, by inventing an avant garde cannon he called MAR. At some point, perhaps involving the Canadian border, Livie recalls that there was some border or customs problem that caused family members to be briefly quarantined. She thinks this may have been due to Chesley not having American citizenship at the time. The other war years were spent in the Gwinn family home at 1809 Dixon Road, Mt. Washington, Baltimore, Maryland. This was not far from the newly built Pentagon and U.S. Army’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland, where Jacques also consulted on his canon concepts.

Chapter 12. Livie says that she attended grade school in Mt. Washington at Mt. Saint Agnes school, under the care of the Sisters of Mercy. She says her father, having to come up with his children’s tuition at the school, jokingly referred to the parochial school as “Mercy Beucoup.”

Chapter 13. Livie reports that the big question for her parents during this period in Baltimore was whether to stay in the U.S. after the war or return to France. She says that her personal recollections of her father in this period are mostly limited to the times he was able to join the family for dinner. She says that the children had strict rules about not talking during meals and that Betsy, to Livie’s great distress, was regularly scolded and spanked for her transgressions.

Chapter 14. In the end, Livie says that her father decided to return to France to supervise rebuilding the refinery that had been bombed during the war at Donges, France. She also discussed how his oil company management experience and general curiosity about the oil company’s worker housing led to his later work in the development of French new towns outside Paris.

Chapter 15. In wrapping up our interview on the Riboud family during the war years, Livie reports on her return to school in Paris after the war, Chesley’s unhappiness with mice when the family was staying at her grandparents Paul (“Bon Papa”) and Louise Riboud’s home on Rue de Danton, and how Bon Papa’s initial disapproval of his son Jacques’s marriage to an American changed over time as over time he “fell in love” with his daughter-in-law, Nancy Gwinn Riboud.