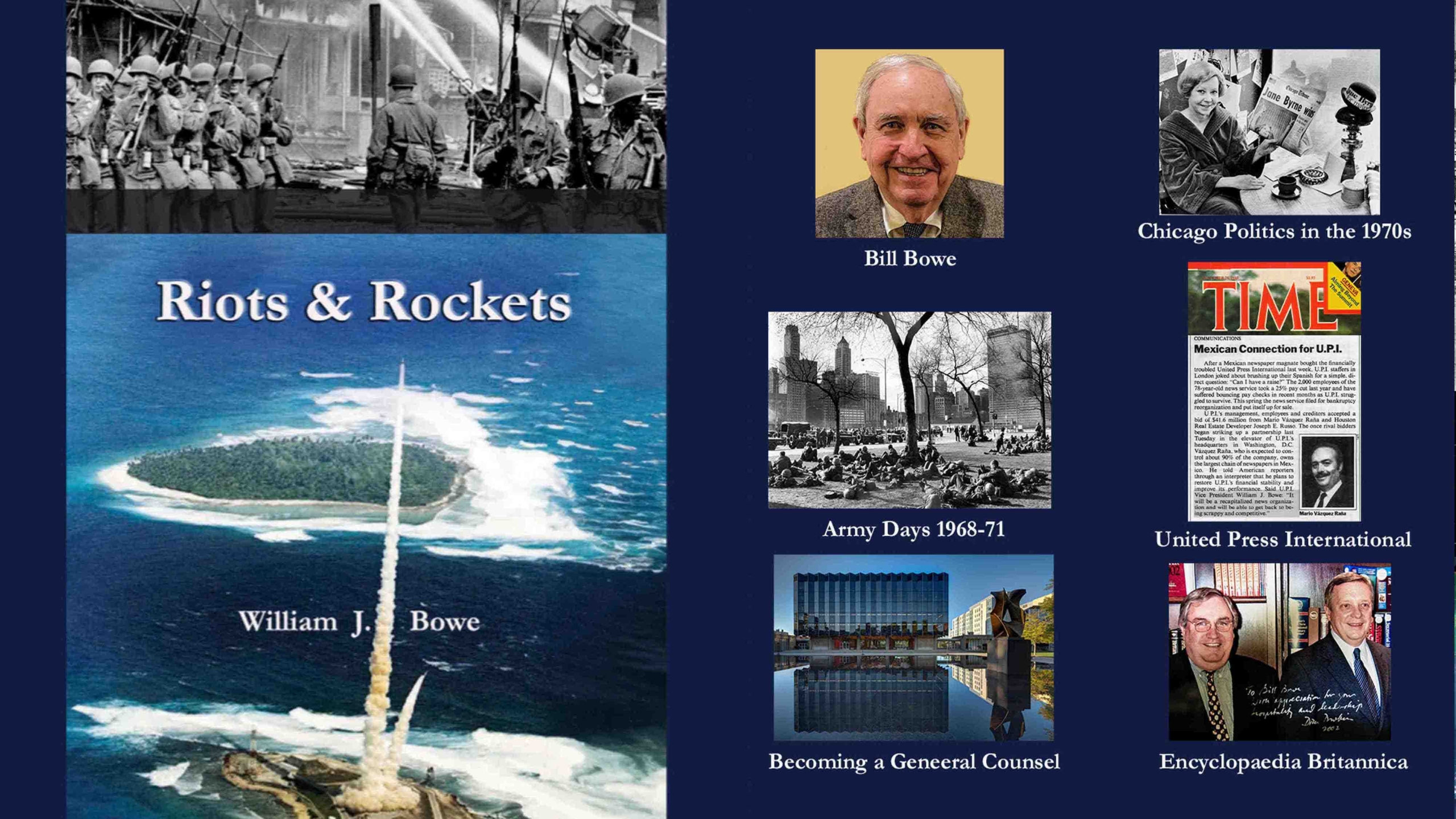

An Early Decision

At about the age of 14 or so, I decided that I would become a lawyer. I would follow in the path of my namesake father and his brother Augustine Bowe. I knew a little bit about what they did and had concluded it was a respectable way to earn a living, if not to get rich. I was acutely aware of the fact that my expensive private school education hinged on maintaining my scholarship. Legal work did seem to provide a solid living and should permit me to someday support a family someday of my own.

In later years, I sometimes wondered why I had cast my lot in this direction at a relatively early age. Part of the answer may lay in the fact that I had my own little basket of insecurities at 14. Getting rid of the question of what I would be when I grew up took one big uncertainty in my life off the table. Not worrying about that would free me to worry about other things, like my father’s declining health or losing my scholarship if my grades faltered.

By the time I got to law school, I had to give thought as to exactly what kind of lawyer I wanted to be.

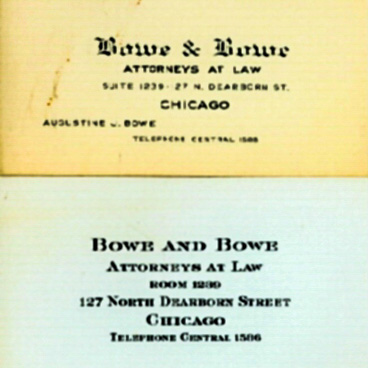

One possibility was to join the family law firm of Bowe & Bowe (later Bowe, Bowe & Casey). It had developed a leading practice in Workmen’s Compensation law in Chicago early in the 20th century. These laws had come into effect to protect people who became injured or disabled while working at their jobs. The laws provided fixed monetary awards in an attempt to keep this class of cases out of a clogged, and relatively expensive court system. The Illinois law had come into effect just as my father Bill and his older brother Gus Bowe were graduating from Loyola Law School in 1913 and 1915. The firm of the two brothers had taken off from the get- go, and over its life course had supported their families, their sister Anna’s family, their cousin John Casey’s family, and by the 1960s, Gus’s son John Bowe’s family. I never gave this option serious thought, however.

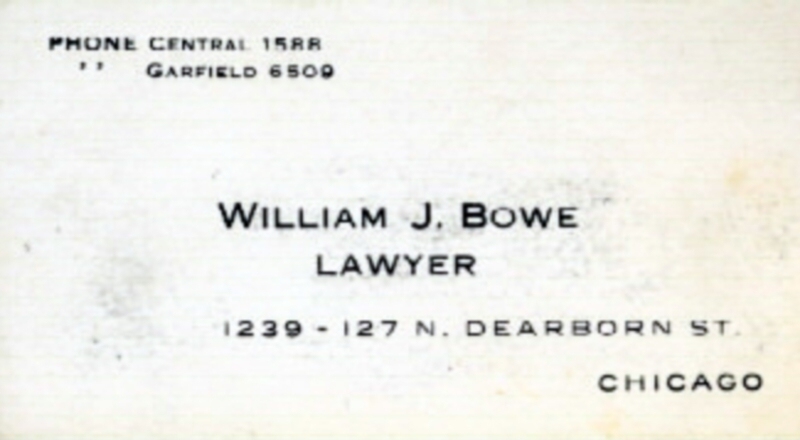

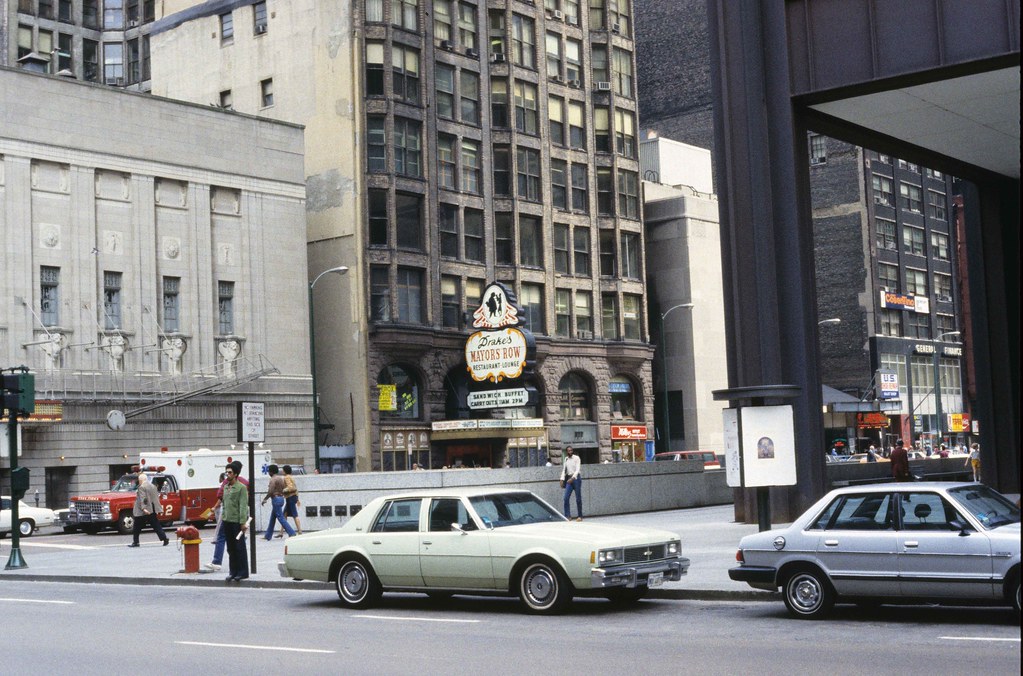

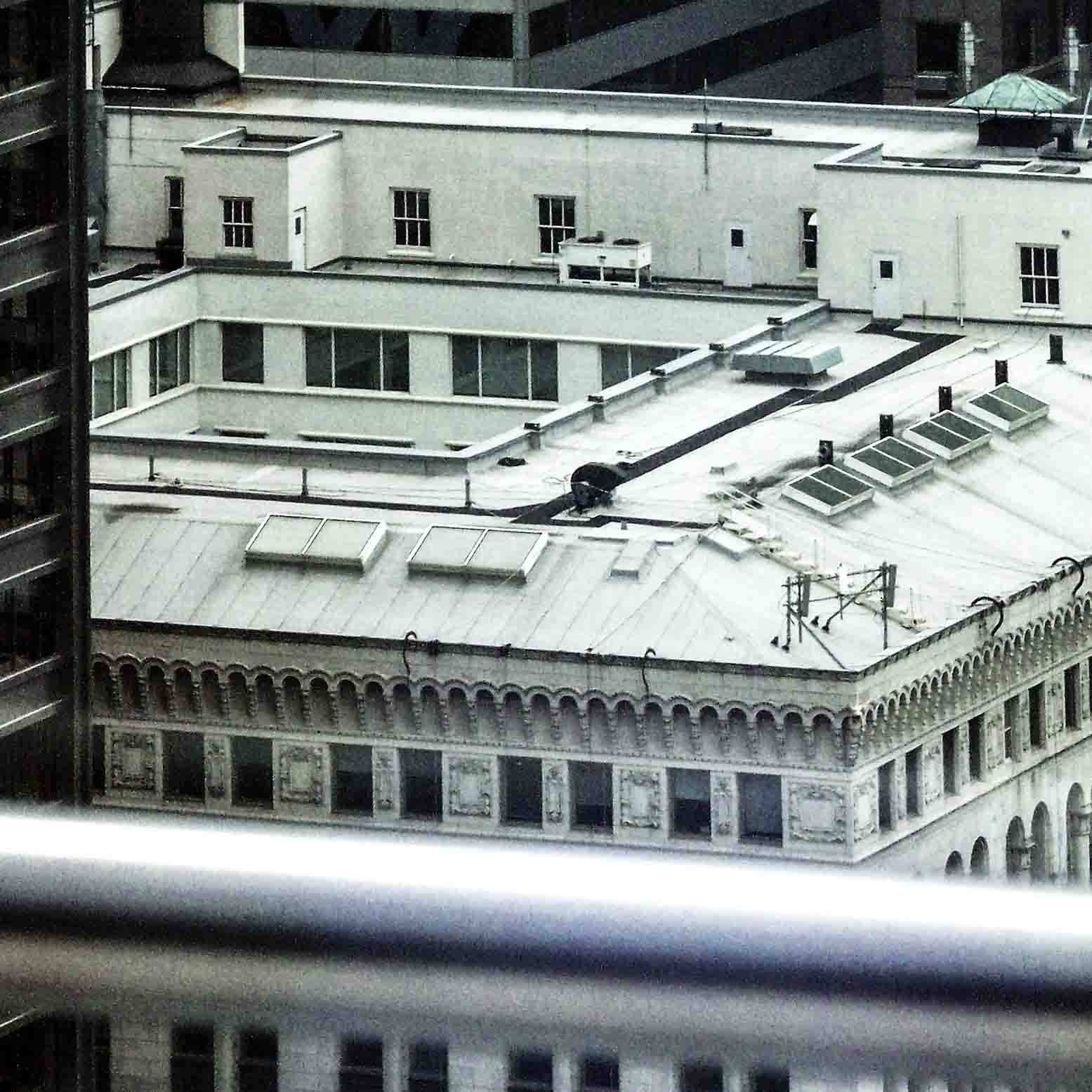

My father Bill, Sr. and his brother Gus had their first law office in 1915 in the Unity Building at 127 North Dearborn Street. The 16-story building owned by John Altgeld. Altgeld was elected Governor of Illinois in 1893, two years after the Unity Building had been completed. Bill and Gus’s uncle, Austin Augustine Canavan had graduated from Yale University Law School in the 1880s and already had an office in the building. I’m sure this accounts for the brothers working in the building even prior to their setting up shop there as Bowe & Bowe.

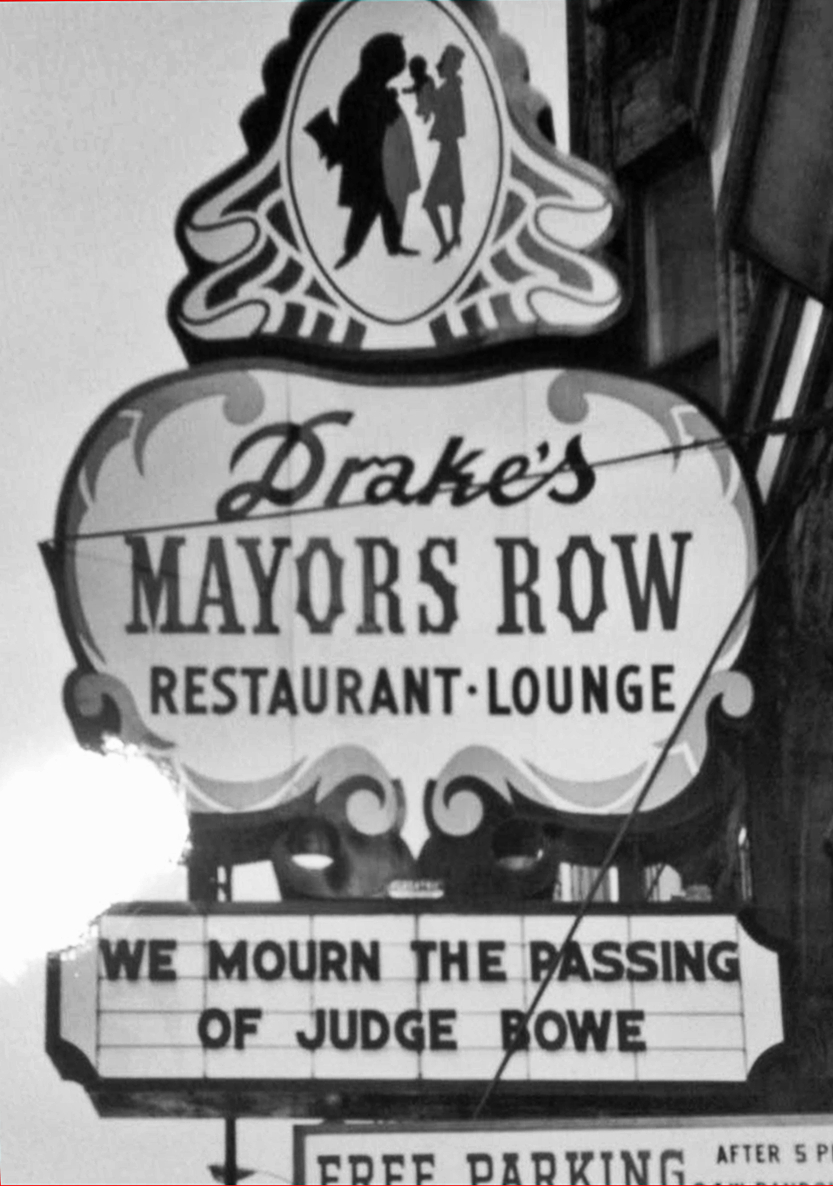

After decades of practice and service as President of the Chicago Bar Association, Gus Bowe had left Bowe & Bowe when he was elected in 1960 as Chief Justice of the Municipal Court of Chicago. By 1965, the courts had been restructured on a county-wide basis and he died that year as the Presiding Judge of the Municipal Division of the Circuit Court of Cook County. Across the street from the Unity Building was the newly built Civic Center court building (now the Daley Center). After Gus’s death, the new building was covered for the first time in funeral drapery. Over at the Unity Building, the letters of the Mayors Row restaurant sign above its entrance read, “We Mourn the Passing of Judge Bowe.” In its last years, after the Bowe & Bowe offices had moved down the street to 7 South Dearborn, the Altgeld building looked out on the famous Picasso sculpture that first graced the Daley Center Plaza in 1967. The Unity didn’t quite make it to 100-years-old mark, however. It was razed in 1989 as part of the redevelopment of what came to be known as Block 37.

In spite of growing up in the midst of a storied family business like this, it was not for me. One of the reasons I never seriously considered joining the family law firm when I got out of law school was the fact that the business had been in decline from at least the 1950s. Partly this was due to my father’s deteriorating health in that period, and partly with Gus’s departure from the firm when he was elected Chief Justice of the Municipal Court. Beyond that, I had occasionally seen some of the intrafamilial conflict and jealousies that can arise in a family business and wanted to steer clear of Bowe, Bowe & Casey for that reason, as well.

While my career choice followed that of my father and uncle, I had ruled out in my mind becoming a litigator and spending my time in court arguing cases as they had. I thought that if I was going to be a lawyer like others in the family, I’d at least be a different kind of lawyer. In law school I briefly considered becoming a State Department lawyer, but in the end, I thought I would head into private practice as a business lawyer. While businesses seemed to be a big part of how the world worked growing up, I had learned next to nothing about how businesses themselves worked and I was very curious as to how they actually ran.

My 1966 summer clerkship at the Ross, Hardies law firm (then Ross, Hardies, O’Keefe, McDugald & Parsons) after my second year in law school had exposed me to the legal complexity and regulatory challenges of several different natural gas, electric and telephone companies. While this was a narrow exposure to what lawyering in the business world might be like, I was hooked on the path of becoming a business lawyer or one sort or another.

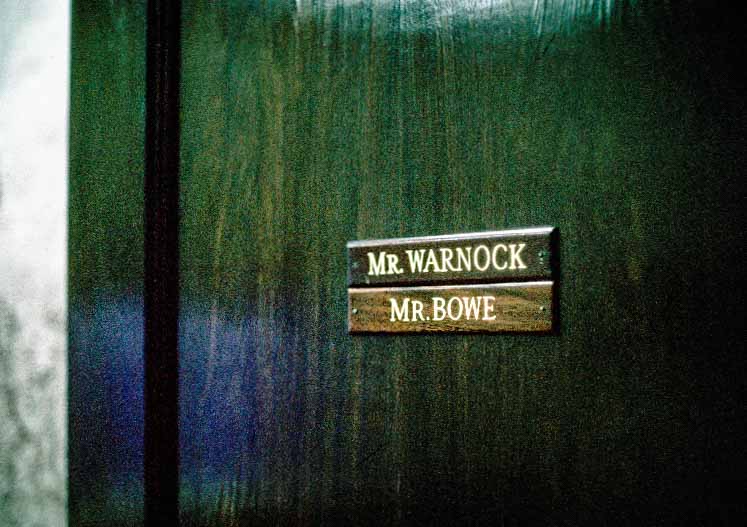

After graduation from the University of Chicago Law School in June 1967, I studied for the bar exam, passed it, and began to practice law as an associate lawyer at Ross, Hardies. The firm’s offices were in the Peoples Gas Building at 122 South Michigan Avenue. As a newbie, I shared a 19th floor office with Bill Warnock, another young associate. Unlike the partners, whose offices enjoyed a Lake Michigan view, we were on the west side of Daniel Burnham’s 1911 building. A summer outing of younger lawyers in the Indiana Dunes gave me a chance to get to know my new colleagues in a less formal setting.

The main building in view from my office was the Dirksen Building, the then new federal courthouse designed by Mies van der Rohe. After Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968, that particular view to the west was dramatically overshadowed by the billowing smoke arising from the buildings set fire along West Madison Street. The race riots in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Chicago that followed King’s death had simultaneously required the deployment of Regular Army troops to supplement police and National Guard forces. As I entered the Army to start my three-year enlistment that May, a city in flames was the image I carried with me. It was a strange coincidence of the day that within six months I would be a counterintelligence analyst in the Pentagon briefing military and civilian officials on the likelihood of Regular Army troops having to again perform riot control duties.

Roan & Grossman

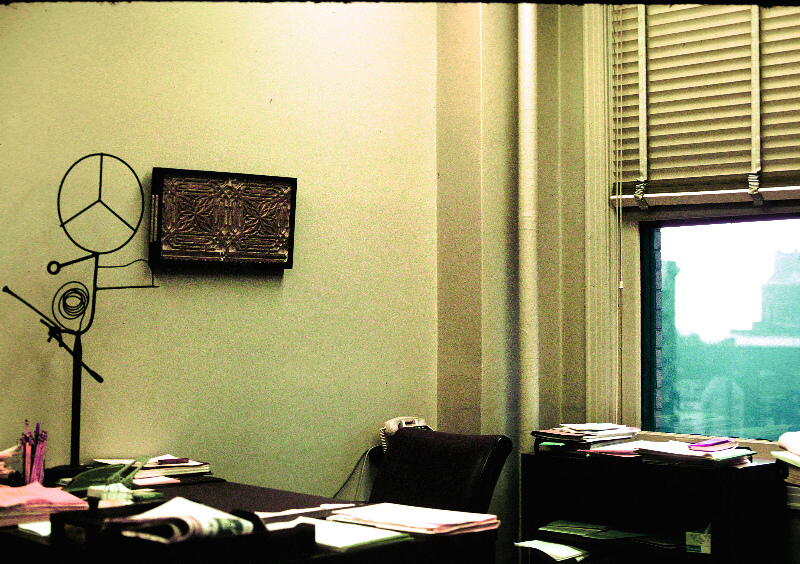

The newly organized Roan & Grossman offices were on the 16th floor of 120 South LaSalle Street in the Loop. My office in the firm’s space had a large window with a perfectly nice view of similar windows on the building’s interior airshaft. While this was evidence of my low position on the totem pole, it beat one of my Pentagon basement office caves I’d worked in. That office space was so small and claustrophobic that my desk took up most of its area. I finally found a exactly the right poster I could put up on one of the walls to cheer me up. The poster looked like a large, open window looking out on a bucolic country scene on a sunny day.

In my brief time at Ross, Hardies before entering the Army, I had been assigned to work as a junior associate lawyer helping Jerry Kaplan, then a senior associate at the firm.

Jerry Kaplan, Des Moines, Iowa 1973

Having personally recruited me at the end of my Pentagon tour, it was a natural shift to return to my prior role in working under his direction. He was a fine lawyer and great mentor to me both at Ross, Hardies and now in his new role as a founding partner of the Roan & Grossman firm.

After graduating from UCLA, Jerry had gone to Harvard Law School, and then had gotten a master’s degree in tax law from New York University. While that made him a specialist in the tax code, I quickly learned tax issues are just one of the myriad of problems corporate lawyers have to deal with. My earlier narrow exposure to utility laws and regulatory issues at Ross, Hardies was now expanded and I began to see to a broader range of day-to-day legal problems being faced by the small to mid-sized business clients represented by Roan & Grossman.

I also began to appreciate that while businesses are organized and operated under the corporate law statutes of the various states, corporate clients in an important sense aren’t at all the abstract entities themselves. The real clients are the flesh and blood humans who have the serious responsibility of making these businesses thrive in a highly competitive environment. Having technical competence as a corporate generalist or specialist is certainly an essential part of any corporate law practice, but the secret sauce of being a truly successful corporate legal advisor is securing the personal trust of the businesses’ managers or owners. That first means being able to listen very carefully to what people are saying, and sometimes to divine what they may not be saying. It also means that you have to be able to give an evenhanded and independent assessment of your client’s situation. You can’t pull your punches just because it’s something the client would rather not hear. I found out that learning how to deliver bad news to a client is every bit, if not more important, than learning how to deliver good news.

The Nature of the Law Practice

I had traded the apparent security of the large Ross, Hardies law firm for what I thought would be a faster development as a lawyer in the more entrepreneurial environment of a small firm. Whereas Ross,

Hardies at the time had large business clients such as a major automobile company and large natural gas, electric and telephone utilities, Roan & Grossman mostly represented small companies. Often that also meant separately representing their owners or managers in their individual capacities. This kind of clientele was often represented on a long-term basis, but sometimes there were short-term clients who came to the firm for one-time transactional work, estate planning, buying a house, getting a divorce and the like.

Most of the businesses the firm represented needed a sophisticated understanding of the tax environment their business dealt with, as well as other corporate law advice. This made Jerry Kaplan, with tax as his specialty well suited to manage the client’s corporate practice as a “billing partner.” Initially, he would then typically deal with strategy or tax issues himself and then parcel out other parts of a client’s legal problems to me. As the 1970s went on, the firm grew as Bill Cowan, from the University of Chicago Law School, and Maridee Quanbeck, from Harvard Law School, joined me as associates in the corporate law area.

Throughout the 1970s I continued to practice law at Roan & Grossman. My one detour was the brief interlude in 1974 and 1975 when I took a leave of absence from the firm to serve as General Counsel and Research Director of Bill Singer’s unsuccessful mayoral campaign against Chicago’s long time mayor Richard J. Daley.

With that exception, I spent the decade nose to the grindstone learning my craft as a corporate law generalist. That meant I was learning to organize and dissolve corporations, merge them, and buy and sell them. In the interim, I was learning how to write their business contracts, manage their litigation, and handle their copyright, trademark, trade secret and other intellectual property rights.

While there was always an ebb and flow to the business, with both busy and dry spells, there were two continuing clients of the firm that I particularly enjoyed and spent lots of time on. One was a steel company, and the other an alternative newspaper born in the generational disruption of the 1960s.

Fabsteel

The Fabsteel Company was a steel fabricating business with operations in Waskom, Texas. My law firm had initially represented its general manager Fletcher Thorne-Thomsen.

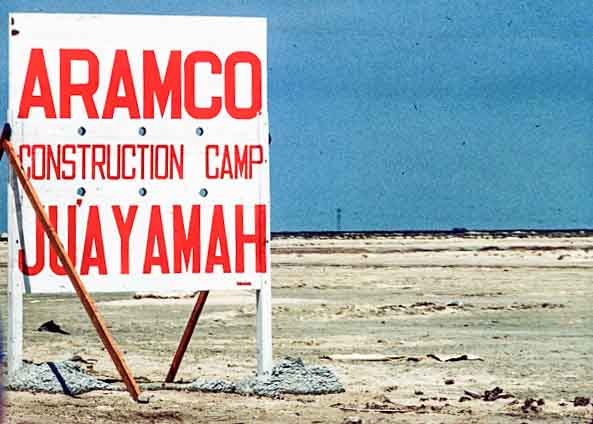

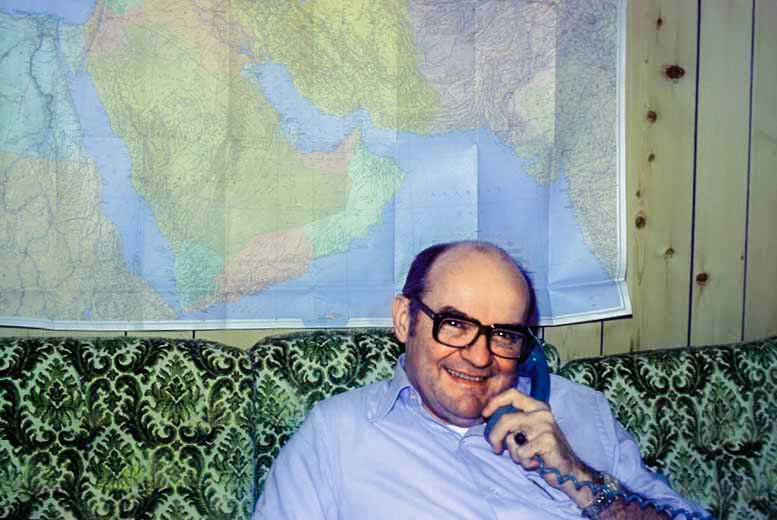

Fletcher Thorne-Thomsen, Saudi Arabia 1977

A Shreveport resident, the concern he headed was a subsidiary of Universal Oil Products. UOP (now Honeywell UOP) at the time was a leading international licensor of proprietary industrial technologies for the petroleum refining, gas processing, and the petrochemical production industries. It had become somewhat bloated in the 1960s as it grew into a conglomerate beyond these fields. It ended up owning businesses as diverse as fragrances, food additives, copper mining, forestry and was even manufacturing truck seats and aircraft galleys. Among these more extraneous assets in its portfolio, was its steel fabrication plant in Waskom.

Part of its specialized work was turning steel mill products such as ingots, slabs, sheets, beams, and rebar into the peculiar shapes needed to build complex industrial facilities. The fabrication process took the different steel mill products and cut them into strange, curved shapes that could end up being welded together into the maze of vessels, towers, ladders, and pipes that make up an oil refinery or plant producing plastics. Fabsteel’s niche in the market was the very high component of labor needed for each ton of the steel it fabricated.

When UOP’s earnings in the 1970s had begun to slide, it decided to stick to its knitting and it sold off most of its forays into non-core businesses. When its Waskom property was to be sold, the most logical buyer was its manager. Whoever it was sold to would likely entail UOP loaning the buyer much of the purchase price to the buyer, hoping it got paid back someday. With Jerry Kaplan in the lead of the transaction, I was in the trenches travelling to Waskom and spending days at a time shuffling between Fletcher’s home in Shreveport, Louisiana and the Waskom plant, a short drive across the Red River in East Texas.

After he bought it, Fletcher had renamed the UOP subsidiary The Fabsteel Company. To represent Fabsteel’s interests properly I had to understand the business from the bottom up. What fun that was! For most of the 1970s, I regularly flew to Shreveport and back on my legal work. From their I would visit fabrication plants it had acquired there, in Mississippi and or Indiana or head out to the nearby Waskom plant. These facilities were enormous, high-ceilinged open structures, with overhead cranes used to move the heavy steel pieces that were being fabricated. The noise could be deafening as torches cut complicated shapes out of the raw steel, and welders were at work everywhere. Periodically, large, finished components would be taken by an overhead crane to a large vat of molten zinc. One dip into the pool of zinc and the piece would be lifted out with a thin galvanized finish that would be ready to last a lifetime outdoors in a refinery or like destination without ever rusting.

For me, leaving my spare lawyer office in Chicago to travel to Saudi Arabia or ramble about one of Fabsteel’s plants in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Indiana was always something I enjoyed. Worksites where the finished products ended up needed to be visited as well. I vividly remember clambering up ladders on stacks and vessels and crossing narrow platforms high above an oil refinery in Houston’s Chocolate Bayou. While this was regarded by some to be grungy work, to me it was truly the high life.

The Reader

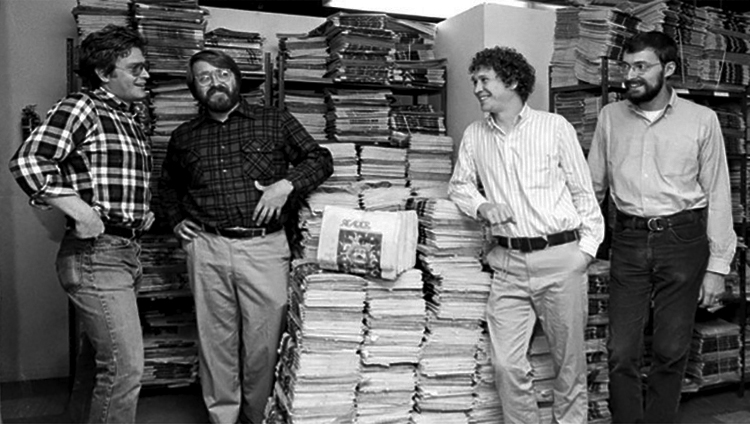

The Chicago Reader was an alternative newspaper that sprang up in Chicago in the 1970s and recently celebrated its 50th anniversary. I worked on some of their corporate issues from time to time and the firm regularly reviewed its content for possible libel exposures. These First Amendment issues were frequent year in and year out and were dealt with by a new litigator with the firm, David Andich. The Reader’s five owners had started it on a shoestring shortly after graduating from college. They were uniformly fun to work with and some became longer term friends long after I ceased to represent their enterprise.

The paper was always given away for free and was completely dependent on advertising. The Reader was only eight pages long in its early days and in 1975 the paper only earned $300,000. However, by 2000, its revenue was on the order of $20 million, and it had gotten fat enough with advertising to resemble one of the mainstream Sunday papers. The paper was more than trendy in this period. It became a must read for anyone wanting to keep up with Chicago’s ever-changing restaurant, cultural and entertainment scene, and it did a fair if offhand job in keeping its eye on local politics and the media. Throughout, it maintained a reputation for publishing long, interesting articles on an astounding array of unusual topics.