Subchapters

- Jane Byrne vs. The Chicago Tribune

- The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

- Mayor Byrne’s 90-Day Report Card

- Mayor Jane Byrne’s Secret Transition Report

- Rob Warden

- “Innuendo, Lies, Smears, Character Assassinations and Male Chauvinist”

- Rally ‘Round the First Amendment

- Will She or Won’t She?

- The Aftermath—Harold Washington Defeats Jane Byrne

Don Rose

Don Rose

2022 Don Rose at Nick Farina Memorial

During the Singer campaign in 1974-1975, I had met Don Rose, a longtime anti-machine and civil rights activist. Later, in 1979, I briefly sought his advice as I launched an unsuccessful effort to defeat the current machine Democratic Committeeman for the 43rd Ward. I don’t remember the advice Don Rose gave me, but it wouldn’t have mattered one way or the other. As it turned out, I was tossed off the ballot for having insufficient signatures on my nominating petitions. I successfully appealed this decision of the Cook County Board of Election Commissioners and the Illinois Appellate Court had ordered my name back on the ballot. When the dust finally settled, I could later tell people I’d lost the election by only seven votes. Unfortunately, these were the votes of the seven Illinois Supreme Court justices who had reversed the Appeals court. Thus was short-circuited my ill fated political career.

Though usually working behind the scenes, over the years Rose had a number of important roles in the city’s electoral contests and political spectacles. In 1966, Rose had served as Martin Luther King, Jr.’s press secretary when King moved into a Chicago slum to bring attention to poverty and racial injustice in the North as part of his Chicago Freedom Campaign. Apart from handling the local press in this effort, Rose served as a King speechwriter and one of his local strategists. He later looked back on this effort as probably the most important thing he ever did.

1966 Don Rose, Rose Bernard Lafayette, John McDermott & Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Two years later in fall 1968, Rose had a major role in the circus surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. My law school classmate Bernardine Dohrn, and her fellow radical and later husband Bill Ayres, were busy organizing the “Days of Rage” riots of the Weather Underground faction of the Students for a Democratic Society. The resultant street battles with police immediately preceded the opening of the Democratic National Convention. I was watching this chaos unfold with more than casual interest given my role at the Pentagon at the time in assessing whether civil disturbances might grow beyond the control of police and National Guard troops. At the time my brother Dick was literally in the middle of the Days of Rage riots in his work for the city’s Human Relations Commission.

Coincident with this SDS unpleasantness, the “Yippies” had also arrived in Chicago for the Convention with their political theater of martial arts practice and nominating a pig for president.

However, SDS and the Yippies were just the opening act. The bulk of the anti-war demonstrators had come to town by the thousands under the aegis of the coalition of groups known as the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam; the MOBE for short.

And Don Rose, building on his recent successful effort for Dr. King, became the press spokesman for the MOBE, and is credited with creating the slogan of the anti-war demonstrations, “The Whole World is Watching.”

A committed man of the left all his life, Rose could manage to work for a Republican if the times called for it. He took particular pride in his management of the campaign of Republican Bernard Carey in 1972 against the sitting Cook County State’s Attorney, Edward Hanrahan.

Hanrahan had been vastly weakened with the public as a result of his deadly raid on Black Panther leader Fred Hampton’s house in late 1969. Most people thought the raid was a botched one at best and a murderous one at worst.

I personally felt so strongly about it that I and Ross, Hardies lawyer Phillip Ginsberg formally requested the Chicago Bar Association to initiate a breach of legal ethics investigation regarding Hanrahan’s conduct.

Notwithstanding the Hampton scandal, when he came up for reelection, he was still the machine candidate and widely presumed to be a winner. That’s when

Don Rose arrived and helped Carey win what would normally have been a losing matchup.

Chicago Tribune contributing Sunday editor Dennis L. Breo captured a profile of Rose in a 1987 portrait. He wrote:

“A flexible strategist who calls himself ”a promiscuous leftist,” Rose set himself apart from other social activists of the 1960s by using his media and writing skills to tie electoral politics to the search for an egalitarian society. “(Leon) Trotsky is a hero of mine because he was a great revolutionary and a great historian of the revolution, but he didn`t ring doorbells. I`ve tried to use electoral politics to achieve a cultural revolution,” he says.

”My real heroes are the giants who led cultural revolutions, who made people see things in a different way: Charlie Parker in jazz, Lenny Bruce in comedy, Ernest Hemingway in language. In a much smaller way, I`ve been trying to do this in local politics.” The revolution never happened, but Don Rose has left his impact on Chicago politics, notably the demise of the old Democratic Machine.

1999 Don Rose, Basil Talbot

Basil Talbott Jr., political writer of the Sun- Times, says: ”Don`s contributions can be blown out of proportion, but there`s a lot to it, too. In 1972 he put together a coalition of blacks and liberals and conservative Republicans and helped Bernard Carey defeat Edward Hanrahan for Cook County state`s attorney. In 1979 he helped create the rebellion of black voters that elected Byrne and defeated the Machine. (Mayor Harold) Washington`s election in 1983 was just icing on the cake.”

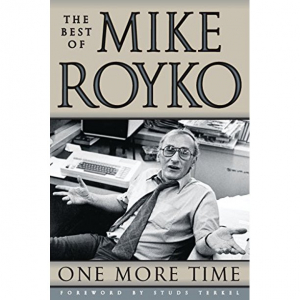

The Tribune`s Mike Royko says: ”It`s hard to measure one person`s contribution to the demise of the Machine because it wore out on its own. Daley stifled those under him, and an entire generation of Machine politicians grew too old to govern effectively. But Don was one of the most consistent opponents of the old politics and one of the very few who never sold out his values one way or the other. He also was very effective, and one of the reasons for his effectiveness is that reporters trust him as a man of his word.”

The Tribune`s Mike Royko says: ”It`s hard to measure one person`s contribution to the demise of the Machine because it wore out on its own. Daley stifled those under him, and an entire generation of Machine politicians grew too old to govern effectively. But Don was one of the most consistent opponents of the old politics and one of the very few who never sold out his values one way or the other. He also was very effective, and one of the reasons for his effectiveness is that reporters trust him as a man of his word.”

Ron Dorfman, a freelance writer and

2007 Ron Dorfman

a 25- year friend of Rose`s, adds: ”The death of the Daley Machine had final causes and efficient causes, and Don was one of the efficient causes dating to the civil rights movement of the early 1960s. The Machine might have died off anyway, but he was an important part of the process. By taking the black vote out of the Daley camp, he set in motion the centrifugal forces that eventually

spun the Machine out of control. He helped change the mosaic of power in Chicago and empower the powerless without seeking any personal power other than in the funny ways creative people seek power. He was able to do it because he`s a walking encyclopedia of Chicago politics. Tell him what block you live on, and he`ll tell you exactly how that block will vote.”

Former alderman and mayoral candidate Bill Singer, who has been both in and out of favor with Rose, says, ”Don is a brilliant strategist, but he is such a true believer it`s easy not to be 100-percent pure in his eyes.”

2016 Bill Singer

With a long history of civil rights and anti-Daley, anti-machine credentials, Rose again was available for a battle against the machine in 1979 when Jane Byrne looked to all like a quixotic loser up against Daley’s successor Bilandic. In the 1975 Democratic primary election for mayor, the Chicago Tribune had taken a pass on the endorsement of any of the candidates, saying it was a question of, “whether to stay aboard the rudderless galleon with rotting timbers or to take to the raging seas in a 17-foot outboard.” By the time Don Rose joined Byrne to manage her campaign, the “rotting timbers” of the Democratic machine had more completely eroded.

And the former Commissioner of Consumer Affairs, Jane Byrne, not only had the temerity to run against the machine’s choice for mayor, she had a tough, down-to-earth, scrappy personality that sharply contrasted with her reserved and bland opponent.

The longtime liberal lakefront constituency in the city’s 5th Ward in the University of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, and the more recently independent northside lakefront wards represented by Simpson and Singer solidly backed her. She also benefited from the growing opposition to the machine in the Black community, which had noticed Wilson Frost’s treatment after Daley’s death. But what really put her over the top was the 35 inches of snow that fell in the two weeks before the February 27, 1979 primary election. It had been met with a perceived collapse of the city’s usually more efficient snow removal efforts. The primary ended with Byrne garnering 51% of the vote and Bilandic 49%.