Subchapters

- A Milestone in Evolution of the Human/Machine Interface

- The Proper Study of Mankind

- The Encyclopædia Britannica First Edition

- The Encyclopedist’s Art

- William Benton, EB Owner and Publisher

- Robert Hutchins, University of Chicago President

- Mortimer Adler, Philosopher

- Charles Van Doren, EB Editorial Vice President

- Reinventing the Encyclopedia in Electronic Form

- Solving the PC Data Storage Problem

- Patricia Wier, EB, Marvin Minsky, MIT, and Alan Kay

- Peter Norton Takes Britannica into the Software Business

- Harold Kester, SmarTrieve, and Compton’s Encyclopedia

- Dr. Stanley Frank, Vice President, Development

- Compton’s Patent R.I.P.—An Afterthought

- A Look Back from Encyclopaedia Britannica

Chapter 5

Inventing the Future—Encyclopaedia Britannica

Who would have guessed that at the end of the 20th century it would be a company founded in Scotland in 1768 that would invent a key part of the mechanics that would let people intuitively navigate the electronic flood of text, sound, and images soon to drench the planet from the internet?

In 1989, 221 years after the company’s founding in Edinburgh during the Scottish Enlightenment, Chicago-based Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., publisher of its eponymous Encyclopædia Britannica reference work, had not only solved this puzzle for the first time, but it was also issued a patent for it. While it may be incongruous that a legacy reference print publisher would be the party to make the discovery, this is exactly what happened.

Normal patents on inventions today have a revenue-producing life of 20 years. The patents Britannica filed for in 1989 were issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 1993 and immediately controversial. Software industry opposition caused the Commissioner of Patents to promptly order a reexamination by the Patent Office. Following the Commissioner’s invitation, the Office cancelled the patent a year after it issued. After more years of litigation by Britannica, another court finally reversed the Patent Office and in 2002, the patent was reissued. Then it was finally up to Britannica to enforce the patent against infringers. The family of Britannica’s Compton’s patents were unusual both in their long and controversial history, but also in that they never earned a nickel. In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit found the patent to have been improperly issued due to a purely technical and procedural error in the original filing papers.

The technical defects meant that this court never got to a detailed ruling on whether then-commonplace GPS navigation systems infringed the patents covering Britannica’s invention. When Britannica later sued its outside patent law firm for legal malpractice for committing the technical error, another court in 2015 denied this claim saying that, if the patent shouldn’t have been issued by the Patent Office in the first place, Britannica couldn’t have been hurt by the law firm’s mistake.

Even though Encyclopaedia Britannica never benefited financially from the extraordinary human/machine interface it had been the first to build, it had reason to be proud of its fundamental achievement. The public filing of its patent application had provided the roadmap for others to follow in quickly developing many other complex software applications besides encyclopedias. The Britannica human/machine interface provided for the first time seamless navigational paths into and through complex databases of mixed media including text, graphics, maps, videos, and audio elements. When developed, the goal had been to have even a nine-year old master the navigation. Of course, today some four-year-old children are playing with computers in a way unthinkable in 1989 when the Compton’s patent application was first filed.

Britannica’s landmark invention had partly to do with the evolution of the personal computer in the mid-1980s. But it also had to do with a small group of encyclopedists who had been struggling for many years before to define what an electronic encyclopedia would look like. The culmination of their work happened to coincide with the coming of age of the personal computer in the nascent consumer market. This was the secret sauce that made the breakthrough in the human/machine interface possible.

This fortuitous combination produced a remarkable cultural result. It meant that for the first time, children, as well as adults, could easily and quickly access and navigate complex and media-rich stores of digital information. It also created a plumbing roadmap for the software design that in later years would prove essential in making user friendly such diverse applications as automobile GPS navigation systems and websites on the internet.

Britannica built on decades of work by computer innovators such as Vannevar Bush, Ted Nelson, Douglas Engelbart, and Alan Kay. These visionaries began to imagine hyperlinks as early as 1945, went on to pioneer the mouse and graphical user interface, and even applied their thinking to the problem of building an electronic encyclopedia.

The Proper Study of Mankind

Although a print publisher throughout its long life, Encyclopaedia Britannica had been keeping abreast of computer developments closely. When the first CD-ROM (for Compact Disc-Read Only Memory) storage discs came out in 1985, Britannica had just put the finishing touches on its multi-decade, massive rewriting of its 1929 14th Edition. The 15th Edition had originally been published in 1974 in a 30-volume set. The 15th Edition was structurally rounded out in 1985 with the addition of a separate, two-volume index to the 15th Edition.

This redesign of the Encyclopædia Britannica in the several decades before the CD-ROM-based Compton’s Encyclopedia launch was a critical precursor to EB’s invention.

The Britannica multimedia search system patent would not have been possible without the specialized learning that grew out of the computer-assisted design of the 15th Edition print set. When the Compton’s patent was reissued by the Patent Office in 2002 after a lengthy reexamination, the stage was set for Britannica to exploit its achievement monetarily.

English poet Alexander Pope began the second epistle of his 1732 work An Essay on Man with this couplet: “Know then thyself, presume not God to scan; The proper study of Mankind is Man.”

His reference to our genome-embedded drive to understand ourselves and catalog our knowledge is symbolized and given tangible shape by the encyclopedic form.

The long, continuous history of the encyclopedia in our civilization is evidence that our collective need for self-examination is hard-wired into our brains.

Thus, the presence of a reference publisher at the center of a critical human/machine interface development in the 1980s was not entirely an accident. It stemmed in part from the very nature of encyclopedias in modern society.

The word “encyclopedia” comes from the Greek words enkyklios, meaning general, and paideia, meaning education.

The effort to create a system of knowledge or circle of learning in the form of an “encyclopedia” spanning humankind’s knowledge has been with us for over 2,000 years, although it hasn’t always been called this. Speusippus, who died in 339 B.C., recorded his uncle Plato’s thinking on natural history, mathematics, and philosophy. Speusippus also apparently attempted to record detailed descriptions of different species of plants and animals.

However, it was Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonne des Sciences, des Arts et des Metiers, published in 1751 in Paris, that first popularized the use of the term encyclopedia to describe works containing a broad compendium of knowledge.

Shortly thereafter, in 1768, the first edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, the oldest and most comprehensive English-language encyclopedia, was published in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The Encyclopædia Britannica First Edition

The three-volume First Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica paid homage to its classical roots in two conspicuous ways. One was a departure from the conventional spelling of encyclopedia.

The use of the æ ligature preserved an ancient bequest of Greek and Roman scribes used to denote diphthongal pronunciation. Even by 1768, this device had fallen out of use except in the most rarefied of contexts.

The other nod to antiquity was the Latinate title itself. It could easily have been called the British Encyclopedia, since Latin had long ceased to be the lingua franca of the educated. In the more than two and a half centuries since that First Edition, Britannica’s stewards have continually changed everything else about the work, but they have always left its unusual title untouched.

The current 15th Edition was first published in 1974. The last print set bore the 2010 year on its copyright, and the permanent cessation of printing the Encyclopædia Britannica was announced in 2012.

Although there were regular revisions of print editions published since the 1930s, readers typically kept their sets up to date by annually buying yearbooks that reviewed recent developments.

Today, the Encyclopædia Britannica is available to a global audience never dreamed of in the history of the print set. In the current era, the online version of Encyclopædia Britannica receives over 7 billion annual page views in more than 150 countries, with in excess of 150 million students using it in more than 20 languages.

The Encyclopedist’s Art

In the twentieth century, encyclopedists were not the only people to worry about how to facilitate access to an ever-growing sum of knowledge. The problem arising from the information explosion of modern times was also noticed by those who helped create it. In particular, the scientists and mathematicians who had created whole new disciplines of knowledge, such as atomic physics and computing machines, had also begun to think about how to increase efficient access by their colleagues and lay people to growing domains of information.

Since the mission of an encyclopedia is to encompass in an abbreviated and accessible form all of our knowledge about everything, the editorial investments needed to create encyclopedias have always been substantial. As a result, the number of encyclopedias has always been relatively few. Also, while there are more than 4,000 distinguished outside contributors commissioned to write articles for an encyclopedia such as the Britannica, there is a much smaller number of career encyclopedists charged with the actual design and creation of the work and its ongoing revision.

In the modern era, professional encyclopedists around the world working continuously in the English language have mostly numbered in the hundreds rather than the thousands. And for over two centuries, the encyclopedists at Britannica have remained the most skilled and respected of their breed. The task of an encyclopedist is an odd one. There are not many of these folks around, and the few around tend to spend their days in single-minded thought on how best to organize a brief, narrative summary of our cumulative understandings of history, art, literature, science, religion, philosophy, and culture.

The encyclopedist’s art has traditionally been more of what to leave out, rather than what to put in.

During my 28-year tenure at Britannica, I had the privilege of working frequently with EB’s Editor for much of that time, Phillip W. (“Tom”) Goetz, and later his successor, Robert (“Bob”) McHenry.

Goetz had been promoted to Editor well before the day I arrived in 1986. He had been the second-in-command Executive Editor during the long development of the 15th Edition. When I once asked him about what that period was like, he said it was the toughest job he ever had to slog through.

The complete rewriting of the 14th Edition had begun in the 1950s and the 15th Edition wasn’t published until 1974.

During that time, Goetz said that, to insure the entire corpus had editorial consistency and “spoke with one voice,” he was detailed to be the one and only person to read and give final approval to all of the 44 million words in the 65,000 articles. The set as a whole was comprised of 32 volumes, each having more than 1,000 pages.

Goetz was possessed of an exceptional intellect and engaging manner, and he never forgot a lot of what he had read, either.

Once, when we had a problem with the development of an Italian translation of Encyclopædia Britannica, I travelled with him to Milan. Arriving on a weekend, we decided to check the common tourist box of visiting the Milan Cathedral.

I was particularly anxious to see it as my mother had taken a snapshot of the church on her honeymoon in 1928. Begun in 1386, it had been added to and refined over the next six centuries.

To take in the exceptional view of Milan from the top of the Cathedral, we climbed the 250 steps to the Duomo roof. As we strolled amongst the marble forest of statues and gargoyles, Tom had been filling me in on aspects of the Cathedral’s construction.

When I asked him what had been going on in the Catholic Church at the time of construction and the years immediately following, my casual question did not elicit a casual answer.

It was all in his head, and he poured it out to me in excruciating detail for the next hour, formulated in perfect paragraph-like sections.

It was an amazing and thorough education for me. While it had been completely casual for him to speak off the cuff as he did, he spoke with the command of a specialist university professor who might have spent an entire career studying and lecturing on the Middle Ages.

William Benton, EB Owner and Publisher

Paralleling this whole development of the computer, encyclopedists at Encyclopaedia Britannica had been thinking long and hard about the proper structure of a modern encyclopedia and how it might be conjoined with an appropriate human/machine interface adapted to the electronic age.

The 14th Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica had been published in 1929, when the company was owned by Sears, Roebuck. That same year, William Benton founded the Benton and Bowles advertising agency in New York City.

The agency prospered with the growth of network radio and its own innovations in the development of national advertising. Among other things, Benton & Bowles is credited with inventing the radio soap opera, which it used as a vehicle to sell its clients’ products.

Benton, later a vice president at the University of Chicago, used the proceeds from his sale of Benton & Bowles to acquire Britannica in 1943, after Sears failed at gifting the company to the University.

Robert Hutchins, University of Chicago President

Benton had been recruited to the University of Chicago in 1937 by his fellow student in the Yale College Class of 1924, then Chicago’s president, Robert Maynard Hutchins. Hutchins was one of the 20th century’s most prominent intellects and educators.

A true prodigy, Hutchins had been named dean of the Yale Law School at the age of 28. He was only 30 at the time of his appointment as Chicago’s president in 1929.

The University’s trustees said notably as they turned down the Sears offer to gift Encyclopaedia Britannica to the school that the University was in the business of education, not the business of business.

Bill Benton knew a good commercial opportunity when he saw it, however, and he seized both the moment and the company.

When Benton purchased Britannica, he agreed to pay the University a 3% royalty on U.S. encyclopedia sales in return for the editorial advice of its faculty. Not long thereafter, Benton appointed Hutchins Chairman of Britannica’s Board of Editors.

The University of Chicago’s connection to Encyclopaedia Britannica lasted more than five decades. Thanks to the simpatico relationship of Benton and Hutchins, it brought the University’s endowment more than $200 million in that time.

In 1974, after an investment of more than $33 million, the 30-volume, 44-million-word 15th Edition of Encyclopædia Britannica was finally published.

The event made the front page of The New York Times. The standalone two-volume index was added to the set as part of a major revision published in 1985 partly because of complaints from librarians.

Mortimer Adler, Philosopher

Mortimer J. Adler, a precocious student (and later critic) of philosopher John Dewey at Columbia University, had also been attracted to the University of Chicago in the 1930s. Hutchins had found appointments for him in philosophy and psychology and at the University of Chicago Law School.

Adler was an evangelist for a broad, liberal education and a strident critic of the disciplinary specialization just then coming to fruition at American universities.

His and Hutchins’s impassioned arguments for an undergraduate curriculum based on the classic texts of Western civilization touched off years of stimulating, though acrimonious, debate at the University in the 1930s.

Adler’s belief in exposing undergraduates to the classics fell in with Hutchins’ view that, “What the nation needs is more educated BAs and fewer ignorant PhDs.”

Wags on the Midway soon were quoted reciting, “There is no God but Adler, and Hutchins is his Prophet.” Students also were heard singing an old New Year’s standard with a new refrain, “Should auld Aquinas be forgot.”

Adler later helped Hutchins complete editorial work on Britannica’s unique 54-volume canon of Western intellectual history, Great Books of the Western World. The set was published in 1952, the same year Adler left the University of Chicago.

Notwithstanding its intellectual gravitas covering the centuries (from Homer, Aristotle, and Aquinas to Freud), Britannica sold “Benton’s Folly” to ordinary Americans with great success.

By the 1950s, the 14th Edition of Encyclopædia Britannica was showing its age. Benton, by this time, had also been an Assistant Secretary of State (he thought up the Voice of America), and a United States Senator (a Democrat from Connecticut and the first to denounce Sen. Joe McCarthy).

After Hutchins left the University of Chicago, he headed the Fund for the Republic think tank, established with help from the Ford Foundation. The Fund had helped finance Adler’s Institute for Philosophical Research in San Francisco.

When Benton was assembling his editorial team to prepare the groundwork for the 15th Edition, he found Adler in San Francisco, where he was finishing his two-volume work, The Idea of Freedom (1958-61).

In December 1962, as Adler celebrated his 60th birthday, his Institute was going nowhere, his marriage had failed, and he was in debt.

Thus, he was in a receptive mood when William Benton reached out:

Come back to Chicago, Mortimer, and help me make a new and greater Encyclopædia Britannica. I’ll not only pay you a princely salary and fund the Institute, but I also support a series of Benton Lectures at The University of Chicago that can be the first step towards a new career for you—and an education for them.

Accepting Benton’s offer to pay him $100,000 a year for life was the smartest thing Mortimer ever did, particularly given the fact that he lived to be 98. Initially when Mortimer returned to Chicago, he set up his own separate office and began to produce standalone books for Britannica. To help, he hired Charles Van Doren, then a former academic very much in need of a job. Robert McHenry, a young EB editor, was seconded to Mortimer’s operation by Britannica and worked there for Van Doren for a number of years.

McHenry would later serve as EB’s Editor-in-Chief in the 1990s. When I recently wrote him asking about Mortimer’s later role in the development of Encyclopaedia Britannica’s 15th Edition, his critique of Adler was a sharp one:

The design and planning of the 15th Edition were in the hands of Mortimer. As Benton’s Charon it could not have been otherwise. It is doubtful whether Benton or any of the managerial class at EB had ever seriously considered what an encyclopedia is or ought to be. Mortimer had one quite definite idea: it should be a tool for educating the user, not simply informing him. For Mortimer, information — what is the atomic weight of carbon? or the capital of South Dakota? — was mostly trivial stuff, no quantity of which amounted to knowledge, to say nothing of wisdom. He imagined the ideal encyclopedia as a synopsis of what the most knowledgeable persons in the traditional academic fields believe they know of the world. And it should be so organized as to lead the user systematically from narrower to broader matters, from simpler to more complex ideas. The goal should be to enable the user to approach an understanding of what Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought or said.”

Mortimer once surprised a meeting of the editors of EB by declaring “I do not consider myself a well-informed person, and I do not wish to be one.” Once the shock passed, he explained “I strive to be an educated person,” and it was his firm belief that such should be every person’s goal. As the Great Books of the Western World was a primary means to that end, so the Britannica should be.

The problem in McHenry’s view was that almost no one used an encyclopedia in that way, “Most everyone looked up atomic weights or capitals. Some might be led on to investigate the history of how atomic weight came to be conceived of and measured or who was “Pierre”? The resultant disaster in McHenry’s thinking was that when the 30-volume, 15th Edition was published in 1974, it was wrongly structured. Short articles were in the Micropaedia volumes, with the articles in this section containing cross references to the long articles in the encyclopedia’s Macropaedia section. A one-volume Propaedia served as an outline of the knowledge in the whole set. It didn’t take long internally at EB for the lack of a standalone index to be seen as a fundamental error of design, and a great impediment to sales in the important educational market. The necessary cure was a major and expensive restructuring of the 15th Edition into 32 volumes, two of which were the long-missing A to Z index volumes. The makeover took over a decade and was not published until 1985, the year I interviewed for the job of General Counsel of EB.

Charles Van Doren, EB Editorial Vice President

In 1962, Adler’s young friend and acolyte Charles Van Doren had received a suspended sentence following his conviction in New York State for perjury in the investigation into the fixed television game shows of the late 1950s.

As a sign that he was looking to the future, Van Doren published a scholarly article, “The Idea of an Encyclopedia,” in the American Behavioral Scientist that same year. In the article, Van Doren argued that American encyclopedias should no longer be mere compilations of facts (a criticism of the 14th Edition). He said they should educate, as well as inform. He also argued against encyclopedias that classified information in artificial pigeonholes reflecting university politics, and spoke in favor of celebrating the natural interrelatedness of man’s knowledge:

It takes a brave man to master more than one discipline nowadays; bravery is not totally absent from our society, and so heroes can be found. But the man who attempts to find the principles which underlie two or more disciplines is considered not brave, but mad or subversive. Those whom graduate schools have put asunder, let no man join together!

Van Doren’s article on encyclopedic form was influential enough to be selected for inclusion along with Vannevar Bush’s 1945 Atlantic essay in the 1967 compilation, The Growth of Knowledge: Readings on Organization and Retrieval of Information. This book also took note of the theoretical work being done in automated text retrieval by Gerald Salton of the Department of Computer Science at Cornell.

When Adler moved back to Chicago to join Britannica, it is not surprising that he quickly found a place for Van Doren. Van Doren was a son of Adler’s old Columbia University teaching colleague and friend, poet Mark Van Doren, and Adler had known him since birth. As Charles Van Doren put it when he spoke at a 2001 memorial service following Adler’s death at age 98:

And then there came the time when I fell down, face down in the mud, and he picked me up, brushed me off and gave me a job. It was the best kind of job: As he described it, one you would do anyway if you did not need the money. First, we worked together making books for Encyclopaedia Britannica. Then I, and many others, helped him to design and edit the greatest encyclopedia the world has ever seen.

The source of Van Doren’s infamy permeated the rest of his life, including his career as an editor at Britannica. At the same time I joined Britannica as General Counsel in 1986, Peter Norton succeeded Charles Swanson as President of the company. When I once asked Norton about Van Doren’s time at EB, he said a few times he had heard a mean-spirited person hum under their breath Dum, Dum, DUM! Dum, Dum, DUM! when Van Doren entered a room. This was the sound of the drums heard on the crooked Twenty-One television show when Van Doren had been feigning to struggle with an answer he’d been given in advance.

The appearance of Van Doren at his mentor Adler’s memorial service in 2001 was a rare public outing. In the years since his 1957 crowning as the new champion of the rigged TV game show, and his hiring shortly thereafter as a “cultural correspondent” on the popular nationwide NBC Today show, Van Doren had mostly avoided the limelight. The big exception to his falling out of public view of course, was his 1959 Congressional testimony before the House Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight. This abruptly made him a pariah for television and also foreclosed a return to the academy. His later career writing books with Adler and as Editorial Vice President of Britannica was notably out of the public eye. He had left EB in 1982, four years before I arrived.

As Executive Vice President of Britannica as well as General Counsel, from time to time I managed a number of relationships with the partners around the world who were publishing translations of the Encyclopædia Britannica into different languages. Usually this was when something in the relationship was going terribly wrong. So, when I began dealing with a copyright infringement of the Encyclopædia Britannica in Greek, I dove into the files to read the correspondence and contractual underpinnings of EB’s relationship with our Greek licensee. What I found was that I was walking in Van Doren’s footsteps. In the 1970s he had negotiated and concluded a very complicated agreement that had substantially benefitted both EB and its licensee over the intervening years.

With this background in mind, after Adler’s funeral service I had a chance to chat with Van Doren. As I had also worked with Adler over the years, I told him I thought he had captured the man nicely in his remarks. When I told him that the Greek language version of the Britannica he had nurtured was still going strong, his eyes lit up as he briefly and enthusiastically spoke about his EB career.

Apart from his comments at Adler’s memorial service, he was rarely heard from in all the years following his humiliating confession before Congress. One other exception was in 1999 when Columbia University’s Class of 1959 invited its former teacher back to speak at its 40th Reunion At that time, Van Doren told them:

Some of you read with me forty years ago a portion of Aristotle’s Ethics, a selection of passages that describe his idea of happiness. You may not remember too well. I remember better, because, despite the abrupt caesura in my academic career that occurred in 1959, I have gone on teaching the humanities almost continually to students of all kinds and ages.

In case you don’t remember, then, I remind you that according to Aristotle happiness is not a feeling or sensation but instead is the quality of a whole life. The emphasis is on “whole,” a life from beginning to end. Especially the end. The last part, the part you’re now approaching, was for Aristotle the most important for happiness. It makes sense, doesn’t it?

When Robert McHenry’s began his career as an EB editor working for Van Doren, he came to have a much more positive view of Van Doren than he held for Adler

Charles Van Doren was acknowledged by those who knew him to be perhaps the most naturally charming man of their acquaintance. Many were doubtless surprised to discover that he could be quite jovial and kindly. It was understood that one did not ask about or allude to the quiz-show affair.

Some 40 years after McHenry and Van Doren first met, when both were retired, McHenry stopped by Van Doren’s Connecticut home for a last visit with his longtime friend and mentor. The visit revealed another side of the man who was known around Britannica as “CVD.” McHenry recalls, “Quite unexpectedly, Van Doren made a point of apologizing to me for having insisted that his name appear also as co-editor of the first three books I had produced while working for him.”

Reinventing the Encyclopedia in Electronic Form

In 1981, Tom Goetz’s retired predecessor Warren Preece published “Notes Towards a New Encyclopedia.” In this article, Preece described the coming electronic encyclopedia.

As one of the architects of the 15th Edition, Preece was intimately familiar with the dense tapestry of cross references that connected related pieces of information spread throughout the Micropaedia, Macropaedia, and Propaedia, the three parts of the encyclopedia. He, more than most, was in a position to ponder the way in which the electronic publishing future might affect a corpus of this nature, and he explored the contours of these possibilities in his article.

Not only did Preece write that his newly envisaged encyclopedia would have an electronic version, but he also saw what Vannevar Bush had not been in a position to see: optical laser-disc technology could be the likely storage medium for encyclopedic data.

Preece also noted that with over 300,000 home computers then in private use in the U.S., online query privileges for up-to-date encyclopedic information was another possible direction for the encyclopedia of the future to take. He also was attuned to the competitive advantages an electronic encyclopedia would have over the book: it could hold more, be searched faster, and be updated more easily.

At Britannica at this time, Van Doren was already leading the charge into Preece’s Brave New World. In May 1980, he had circulated to his colleagues a new agreement between Britannica and Mead Data Central. The four-year agreement called for the full text of the Encyclopædia Britannica to be put online as part of the Lexis-Nexis service.

Mead was to pay Britannica up to 25 percent of Mead’s revenues from encyclopedia subscriptions. While being careful to discourage copyright infringement by not permitting subscribers to print articles from the encyclopedia, Britannica had now committed itself to an electronic future in more than a symbolic way.

Solving the PC Data Storage Problem

Britannica editor Warren Preece had been able to foresee the possibility of an optical disc encyclopedia because of breakthrough engineering developments that had taken place in Europe and Japan. Klass Compaan, a physicist with Philips research based in Netherlands, had conceived of the compact disc in 1969 and, with Piet Kramer, had produced the first color videodisc prototype in 1972. Philips then worked with Sony to develop a smaller compact disc standard for just storing audio signals.

The audio compact disc that emerged was made with a polycarbonate substrate, molded with pits that permitted a laser beam to read timing and tracking data. The so-called Red Book format of the compact disc was released in Japan and Europe in 1982, and in the U.S. the following year. A derivative format, designed to hold multimedia information and be played back on a computer, was given the unwieldy name Compact Disc-Read Only Memory, CD-ROM for short. This was launched into the nascent personal computer market in 1985, several years after the first prototypes had been shown.

Grolier Publishing quickly put a text-only encyclopedia on a videodisc and also a CD-ROM in 1985. Most early CD-ROMs published were specialized compendia designed for commercial, not consumer, use. Navigation was accomplished through rules-based Boolean text string searches. Discs with sound, pictures, video and animation, although supported by the CD-ROM format, were not available.

Microsoft believed that for sales of its operating system to grow at an exponential rate, software developers needed to be encouraged to use the new CD-ROM storage media to create compelling software for consumers. The assumption was that this would drive consumers to regard PCs in the home not just as gaming facilitators, but as a requirement for their children’s education. To this end, Microsoft showed off a CD-ROM multi-media encyclopedia demonstration disc at a CD-ROM developer’s conference it held in 1986. The dozen five-page articles on the demonstration disc contained text, graphics, sound, a motion sequence, and animation.

There were several prime movers of Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia.

Patricia Wier, EB, Marvin Minsky, MIT, and Alan Kay

Britannica had first acquired a large mainframe computer in the 1960s. It had primarily been used to manage the company’s direct mail and installment sales activities, though it also did the usual accounting applications and managed the payroll and accounts receivable functions. In 1971, Britannica hired Patricia A. Wier to help manage computer systems and programming operations. Wier had been lured away from a computer management position at Playboy magazine’s Chicago headquarters. A quick study, Wier was promoted to head Britannica’s computer operations within the same year.

Wier was determined to broaden the use of computers within the company, and before long Wier helped graft the in-house editorial system onto Britannica’s existing mainframe computer. This system was used to help produce the massive 15th Edition. It was not until the early 1980s, however, that Britannica moved to a stand-alone mainframe computer completely dedicated to editorial operations. At that time, all editorial and production work was put online, including page-makeup and indexing.

It was at this juncture that Wier was promoted to vice president of corporate planning and development. She was charged with developing or acquiring new products that would see Britannica into the future, particularly bearing in mind the new computer technologies that were coming to the fore. Soon she and editorial vice president Charles Van Doren began calling on various leading lights in the field of computer development to get ideas about the directions Britannica electronic products might take. Because Wier wanted to explore at a sophisticated level how the computer developments of the future might be put to use by a reference publisher such as Britannica, she traveled to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MIT was then, as it is today, at the cutting edge of important computer developments. The people that she engaged at MIT included “artificial intelligence” guru Marvin Minsky at the MIT Media Lab. Minsky introduced her to a former student of his, Danny Hillis, by then at the supercomputer manufacturing startup Thinking Machines. Both were intrigued with how computer technology might be applied to such an enormous and fascinating database as the Encyclopædia Britannica. Of particular interest to everyone Wier met was the dense indexing within the set that already existed, interconnecting as it did all parts of the database.

Wier recalls that when she met with Minsky at his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, and entered the large casual room where their meeting was to take place, three grand pianos scattered around the room sounded the opening chords of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as the door opened.

Minsky had other gadgets like this in his home, all reflecting his never-ending fascination with technology and its uses, both playful and serious. Grand pianos seemed the order of the day among these leading East Coast technologists.

When Minsky and Wier visited the home of Sheryl Handler, a co-founder with Hillis of Thinking Machines, Minsky sat down at her new Bösendorfer grand piano and expertly indulged his passion for magnificent music machines.

Though all Wier’s Boston-based interlocutors were singular, none could fully compete with one of Handler’s achievements. She had appeared in a Dewar’s Scotch whisky advertising profile next to the quote, “My feminine instinct to shelter and nurture contributes to my professional perspectives.”

Wier also met briefly at this time with Nicholas Negroponte, director of the Lab. Wier and others were curious about how to use what was then called artificial intelligence to permit the recovery of pertinent electronic data in a more sophisticated manner than through keyword searching alone.

During this period, Wier and then Britannica USA president Peter Norton also met with computer pioneer Alan Kay to discuss how rapidly developing computer technology might impact an electronic encyclopedia. At the time, Kay was working with Atari to produce electronic games, but Wier recollects that he was fascinated with the content of Encyclopædia Britannica and came to Chicago to visit Britannica’s corporate headquarters to learn more.

His sneakers and jeans, while standard mode of attire for Silicon Valley, caused heads to turn and eyebrows to raise at the then-straitlaced Britannica Centre. The requirements for more formal business garb at Britannica and other offices in downtown Chicago didn’t disappear until well into the ’90s. Wier and Kay, who had his own associations with the MIT Media Lab, also brainstormed about someday using encyclopedic information in voice-controlled graphics on walls in the home.

In 1983, with her research complete, Wier proposed to Britannica’s board of directors that it embark on the creation of an interactive electronic encyclopedia. Wier, who retired in 1993 as president of Britannica USA, got an answer akin to the one given by the University of Chicago’s directors when they turned down Sears’ Britannica gift. Wier remembers she was told in no uncertain terms, “We sell books!”

At Atari’s Sunnyvale Research Laboratory, Kay consulted the next year on an encyclopedia research project sponsored by Atari, the National Science Foundation, and Hewlett-Packard. Joining Kay as a consultant on the prototype Encyclopedia Project was Charles Van Doren, recently retired from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Peter Norton Takes Britannica into the Software Business

Although not willing to follow Wier’s advice in 1983, Britannica’s board of directors did believe the company needed to get closer to the emerging personal computer market. That year, Encyclopaedia Britannica Educational Corporation, which I later served as president, published a dozen floppy disk educational titles that it had acquired for the Apple II platform. Soon Britannica decided to directly acquire its own software development capability. In 1985, it purchased Design Wear, EduWear, and Blue Chip, three small San Francisco-based software publishers also selling 5¼ inch floppy magnetic disk products.

With the introduction that year of the CD-ROM format, Britannica also began to think about how it might exploit this new medium. The question was not a simple one. The Encyclopædia Britannica itself was thought to be too massive to be put on a CD-ROM, even with minimal indexing and a text-only format.

Also, the entire business model of the company was still built on selling its flagship, multi-volume print work at a purchase price of $1,200 and up, depending on the binding. The direct selling sales culture that prevailed at Britannica was no more receptive to the idea of an inexpensive, electronic alternative to the print set than it had been when Patricia Wier first made her recommendation.

In 1987, Britannica’s management, led by former Englishman, now American citizen, Peter Norton, hit on a solution.

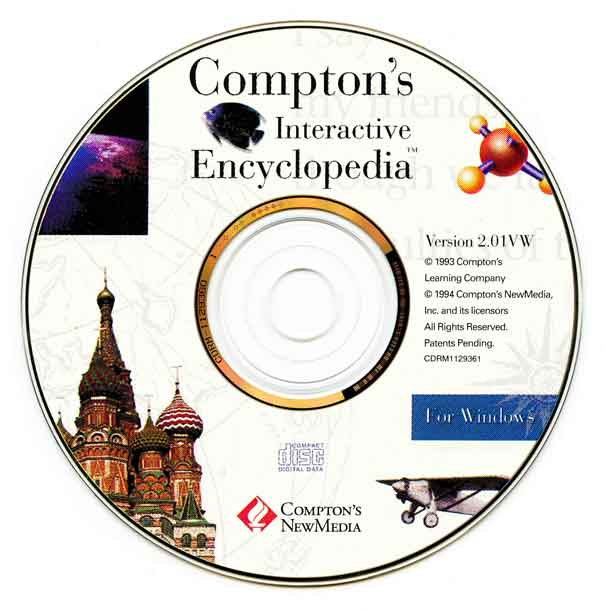

This time the plan was not seen as a threat to the sales force, and it was endorsed by the board of directors. Instead of putting the Encyclopædia Britannica on a CD-ROM, Britannica would become a leader in the newly developing software publishing industry by building a multi-media CD-ROM version of its student-oriented Compton’s Encyclopedia. At the time, the Compton’s print set was given away free as a premium to purchasers of the more expensive Encyclopædia Britannica print set.

Harold Kester, SmarTrieve, and Compton’s Encyclopedia

After further analyzing the potential market for such a work, Stanley Frank, in charge of development by then, decided in 1988 to partner in its development with Education Systems Corporation of San Diego, California. ESC had expertise in software development through building networked educational products for the school market. ESC chose as its text search engine subcontractor the Del Mar Group. Del Mar was a Solana Beach, California, venture capital startup, with funding from Japanese computer maker Fujitsu.

Del Mar’s chief scientist, Harold Kester, had already been building CD-ROM reference publications, though not for the consumer market. Importantly, Kester was also a student of the work of Gerald Salton at Cornell University. Salton had been doing pioneering research into the mathematical principles underlying automatic text retrieval. As Greg Bestik, ESC’s head of development, Kester, and Britannica’s editors and software engineers got together to plan the design of what became Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia, they had one clear instruction from Britannica’s management: Britannica was ready to invest millions of dollars in the product’s development, but it must publish a revolutionary offering that would be a clear breakthrough in simplifying a user’s interaction with computers.

This would not be a text-only product like Grolier’s. The depth of Britannica’s vast holdings of reference media in film, pictures, animations, maps, and sound would all be made available for close integration with the Compton’s encyclopedic text. Kester’s great contribution to this enterprise was to produce a natural language search engine that would help permit the prototypical nine-year-old to easily search the entire database for articles of interest.

Instead of expecting a nine-year-old to master the intricacies of Boolean logic in constructing search queries (“Sky” AND “Blue”), Britannica’s nine-year-old needed only to type in the search box “Why is the sky blue?” That would be enough for Del Mar’s SmarTrieve search engine to take the user to the answer.

Shortly after Del Mar’s organization in 1984, it became one of the first CD-ROM publishers the next year. It published the fifth CD-ROM in the United States in 1985. It was a prototype of a product intended for bookstores that would permit consumers to interact with a database and be guided to titles of interest. Its SmarTrieve search system was licensed to other CD-ROM developers, and, in 1986, Del Mar briefly had the largest installed base of CD-ROMs in the country.

Informed by Gerald Salton’s earlier work, SmarTrieve’s natural language search and retrieval system went far beyond the usual database search engines of its day.

Duly impressed, Britannica purchased SmarTrieve and hired Kester and his team as soon as the networked version of Compton’s product was complete. When Britannica and ESC signed their co-development agreement in April 1988, the Del Mar Group dived in to help with the preparation of the design document. This was completed in July 1988. It set forth in elaborate detail the architecture of the Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia that would be published in the new CD-ROM format in the fall of the following year.

The design document was very much a collaborative one. ESC had talented computer programmers and educational experts in San Diego and Austin, Texas sites. Harold Kester and his search engine group worked from Solana Beach, California, and the Britannica editors and software experts were in Chicago and San Francisco. Over the years, when I visited the brilliant group in Solana Beach and later La Jolla, California, I had a chance to observe at close hand the intellectual leadership and creative genius with which Harold led his team. He was truly the right person at the right time for this breakthrough.

During development, between 40 and 80 individuals were active at any given time in working to bring the design document to life as a fully functioning product. This would be no prototype or demonstration vehicle for show and tell at a futurists’ conference. They were about inventing and building the real thing. If they succeeded, it would be proven that Ted Nelson’s dream of creating hyperlinks—called Project Xanadu—could come true. Something along the lines of what Ted Nelson had surmised could actually be reduced to practice and change the world forever.

Those on the design team with a background in educational psychology were particularly sensitive to the fact that children learned in different ways.

They pressed home the desirability of having different ways, both textual and graphical, for users to access the same information.

Dr. Stanley Frank, Vice President, Development

Thus, from the beginning, the novel idea of developing an architecture based upon multiple search paths to related information was central to the product. Also fundamental to the design were reciprocal hyperlinks between related data contained in other search paths. With a product that was easy to use and that could easily facilitate different styles of learning, the group felt it was building a blockbuster, both for the network market within schools, as well as for the stand-alone consumer market.

This combination of ESC’s computer networking programing expertise together with Britannica’s skilled encyclopedists was a unique combination for the times. And building an electronic database that went beyond text to include sound, animation, video, and maps could never have been accomplished without the millions of dollars that was invested by Britannica both before and during the development of the Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia product. This unusual combination of human resources, coupled with a subset of Britannica’s rich editorial content, turned out to be the requirements for building the software needed to bring a highly complex digital work to life.

If anyone doubted the difficulty of pulling this task off, for a parallel they needed only look at the decades-long and costly failure of Ted Nelson’s Xanadu effort. It had never been able to actually produce a useful product that actually worked.

In fall 1989, Britannica released a network version of Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia for schools at a press conference at the New York Academy of Science. The news media was out in force, recognizing the product as potentially noteworthy. Dr. Stanley Frank, who had overseen the development process as EB’s Vice President, Development, demonstrated the Compton’s CD-ROM for a national television audience through a live presentation that reached the nation on ABC’s Good Morning America television show.

The consumer version of Compton’s CD-ROM was published shortly after, in March 1990 at a price of $895. Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia, on a single CD-ROM disc, contained an amazing 13 million words, 7,000 images, and numerous movies, animations, and sound clips.

Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia made a splash when the media took notice. Said Newsweek of the breakthrough computer interface:

Computers aren’t just smart typewriters and zippy number crunchers anymore. … Yet so far hype has outstripped hopes in the growing collection of multimedia programs. Like dazzling Hollywood flops, most have turned out to be long on technology, but short on substance. Until Compton’s. … Just getting that much information on a disc is impressive enough. Yet the beauty of Compton’s is in the links—everything is woven together so the user can quickly move between related bits of information. Thanks to ingenious design, the program is so simple that, literally, a child can use it. … Hit a difficult word? A click will bring up the definition—and if your PC has sound capability, the machine will even pronounce it for you. Whetted appetites: A staff of 80 writers, editors, designers and programmers worked for two years to bring the product to market.

The effect on people experiencing Compton’s for the first time could be stunning. Former Vice President Walter Mondale, like his political patron saint Hubert Humphrey before him, served on the Encyclopaedia Britannica board of directors.

Shortly after the Compton’s product was released, I escorted Mondale to see the newly developed product with other directors at the Oakbrook Center Mall outside Chicago. He read with interest his own biographical entry reflecting his service as Vice President. After looking with less interest at the text of the entry on Richard Nixon, he got up from the keyboard and turned to leave.

Seeing he had ignored the sound button on the entry, I quickly clicked on the audio icon in the Nixon article. When the computer speakers boomed Nixon’s disembodied voice (“Well, I’m not a crook!”), Mondale turned around, frozen in amazement. He was obviously not prepared for this Nixon redux and was stunned by the product coming to life this way.

Computer hardware manufacturers quickly saw Compton’s could help sell their boxes to consumers. Tandy Corporation immediately struck a deal with Britannica to sell its new multimedia PC for $4,500, with the $895 Compton’s disc thrown in for free. IBM, not wishing to be left behind, quickly gave Britannica a million dollars towards EB’s continued development of the product, making sure it was adapted to IBM’s newly planned multimedia computer entry.

Compton’s Patent R.I.P.—An Afterthought

When the Patent Office reversed course in 1994 and withdrew the patent it had issued just the year before, Britannica challenged the action and brought suit. Years later, a federal district court in Washington, D.C., found the Patent Office in error and confirmed that no invalidating prior art had preceded the Britannica invention. The result was that in 2002, the Patent Office again issued the Compton’s patent. Finally, 13 years after filing its original patent application, Britannica could begin to try to monetize its invention.

By this time though, the technology associated with the patent had rapidly evolved. When Britannica approached non-encyclopedia companies asking them to license the patent, they declined to acknowledge the patent’s validity, notwithstanding its prior validation after two lengthy investigations by the Patent Office. In response, Britannica brought another lawsuit asserting its rights against some of the infringers. In this subsequent litigation, again no dispositive prior art was ever presented showing that the invention had been made by anyone else before the Compton’s patent application was filed in 1989.

As could be expected, attorneys for one of these parties being sued for infringement began wading through the already complex patent history. Lo and behold, they found a useful needle in the haystack. They discovered years after the mistake could have been cured that the Washington, D.C., law firm Britannica had hired to draft and file the patent application in the Patent Office had dropped the first page of one of the Xerox copies of the patent application it had filed. It had also made a scrivener’s error by dropping a routine boilerplate phrase required to be recited in the application.

Dropping the page in a copying error and failing to put in the usual technical language required by the patent statute was bad news for Britannica. The result was that the Compton’s patent was ruled invalid for technical reasons having nothing to do with the substance, novelty, or importance of the invention itself.

But for the law firm’s lapse, it appeared that the invention would have otherwise gone on to produce substantial royalties. By making public the details of the invention in its 1989 patent application, it had been possible for other companies to quickly digest the nature of the invention and incorporate it into their own products. The application’s detailed drawings and the textual descriptions of the innards of the invention gave rise to the immediate and wide dissemination of exactly how to structure and write the complex software needed to permit simultaneous access to multiple and disparate databases of text, sound, images, and videos.

The only good news in this case’s outcome for Britannica was that it had inadvertently cemented a perfectly good legal malpractice claim against the law firm that had negligently botched its job.

In the course of proving a case of legal malpractice involving a patent, the party alleging malpractice must show that a lawyer’s mistake actually damaged it. If you’re defending against such a claim of malpractice, you can get yourself off the hook if you can show that the patent in question was invalid and never should have been issued.

Therefore, when Britannica sued the law firm for legal malpractice, there was what’s known as “the case within the case.” This meant that the outcome of Britannica’s malpractice case would also finally bring a ruling on the underlying merits of its patent. If this turned out to be good news for EB, it would be bad news for the Washington law firm. If the damages it was ordered to pay exceeded its malpractice insurance, it might bankrupt the law firm and perhaps some of its partners.

However undesirable it was for Britannica to have to sue a Washington, D.C., law firm in a District of Columbia court, it was unavoidable. When the dust finally settled in 2015 on this final dispute involving the Compton’s patent, the federal district court hearing the case ruled that the invention was not patentable. This meant that while legal malpractice may have occurred, Britannica couldn’t have been damaged.

In arriving at this conclusion, the court took a fresh look at the basic requirements for a patent to issue. It set aside the fact that in two separate instances the Patent Office had never found or ever seriously considered whether the software patent in question constituted what’s called “patentable subject matter.” Everyone before had always thought that it was, as the U.S. Supreme Court had long before ruled that software inventions could be patented.

Under the U.S. Patent Act, for a patent to be valid, it must have the attributes of utility, novelty, nonobviousness, enablement, and it must cover patentable subject matter. There was no fresh evidence presented to the court in the malpractice case that the Compton’s patent didn’t meet the tests of being useful, novel, and nonobvious. It also had clearly enabled others ordinarily skilled in the art to replicate the invention. However, the court decided that Britannica’s patent failed the remaining requirement for a valid patent because the patent did not meet the court’s definition of “patentable subject matter.”

The court said that “abstract ideas” were not patentable under the longstanding rule that an idea itself is not patentable. It said that the Compton’s patent claims were drawn to the abstract idea of collecting, recognizing, and storing data to be easily found and retrieved, and that this was an abstract concept and therefore not patent-eligible. In its ruling, the court put it this way:

A “database” is nothing more than an organized collection of information. Humans have been collecting and organizing information and storing it in printed form for thousands of years. Indeed, encyclopedias—described as a type of “database” in the specification—have existed for thousands of years. For just as long, humans have organized information so that it could be searched for and retrieved by users: For example, encyclopedias typically are organized in alphabetical order and are searchable using indexes, and articles generally contain cross-references to other articles on similar topics. These activities long predate the advent of computers. Such fundamental human activities are “abstract ideas.”

Thus, it was that a quarter century after the Compton’s Patent application was filed in 1989, the last hope of Britannica profiting from its investment in the invention was extinguished.

Having hired the law firm that drafted the Compton’s patent application in 1989, I was present at the creation, as it were. I had subsequently spent 15 years directing and supervising the torturous regulatory and judicial quagmire that ensued. As it turned out, I missed the third act of the Compton’s patent drama when Britannica’s malpractice claims finally died in 2015. My absence from the finale was a function of my 2014 retirement at the age 72 after 28 years as Encyclopaedia Britannica’s General Counsel.

Engaged in the chasing of the Compton’s patent holy grail for all those years, I have a few simple afterthoughts as to how it all went down.

I think the patent would never have gotten in trouble in the first place had Britannica’s Stanley Frank not overreached in pursuing his dreams of a quick payoff. In the 2005 book Intellectual Property Rights in Frontier Industries—Software and Biotechnology edited by Robert W. Hahn, authors Stuart J. H. Graham and David C. Mowery write that shortly after the Patent’s issuance by the Patent Office in 1993:

Compton’s president, Stanley Frank, suggested that the firm did not want to slow growth in the multimedia industry, but he did “want the public to recognize Compton’s NewMedia as the pioneer in this industry, promote a standard that can be used by every developer, and be compensated for the investments we have made.” Armed with this patent, Compton’s traveled to Comdex, the computer industry trade show, to detail its licensing terms to competitors, which involved payment of a 1 percent royalty for a nonexclusive license. Compton’s appearance at Comdex launched a political controversy that culminated in an unusual event—the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office reconsidered and invalidated the Compton’s patent. On December 17, 1993, the USPTO ordered an internal reexamination of Compton’s patent because, in the words of Commissioner Lehman, “this patent caused a great deal of angst in the industry.” On March 28, 1994, the USPTO released a preliminary statement declaring that “[a]ll claims in Compton’s multimedia patent issued in August 1993 have been rejected on the grounds that they lack ‘novelty’ or are obvious in view of prior art.”

In the July 1994 issue of Wired magazine, the article “Patently Absurd” threw further light on how the Compton’s patent issuance created an almost instant political bonfire:

The Compton’s Patent contained 41 claims that broadly covered any multimedia database allowing users to simultaneously search for text, graphics, and sounds—basic features found in virtually every multimedia product on the market. The Patent Office granted the patent on August 31, 1993, but it went unnoticed until mid-November, when Compton’s made the unusual move of announcing its patent at the computer industry’s largest trade show, Comdex, along with a veiled threat to sue any multimedia publisher that wouldn’t either sell its products through Compton’s or pay Compton’s royalties for a license to the patent. Compton’s president, Stanley Frank, stated it smugly for the press: “We invented multimedia.”

The denizens of the multimedia industry thought otherwise. In dozens of newspapers around the country, experts asserted that Compton’s Patent was clearly invalid, because the techniques that it described were widely used before the patent’s October 26, 1989, filing date. Rob Lippincott, the president of the Multimedia Industry Association, called the patent “a 41-count snow job.” Even Commissioner Lehman thought that something was wrong.

“They went to a trade show and told everybody about it. They said they were going to sue everyone,” says Lehman, who first learned of the Compton’s Patent from reading an article in the San Jose Mercury News. “I try not to be a bureaucrat,” he adds. “The traditional bureaucratic response would be to stick your head in the mud and not pay attention to what anybody thinks.” Instead, Lehman called up Gerald Goldberg, director of Group 2300 [in the Patent Office], to find out what had happened.

Like Lehman, Goldberg had learned about the Compton’s Patent from reading the article in the Mercury News. “We pulled the patent file and I took a look at it,” recalls Goldberg. “I spoke with the examiner. We felt the examiner had done an adequate job.” In this particular patent application, says Goldberg, the Compton’s lawyer had included an extensive collection of prior art citations—none of which described exactly what the Compton’s Patent claimed to have invented. Without a piece of paper that proved that the invention on the Compton’s application was not new, the examiner had no choice but to award Compton’s the patent.

To cap things off, Compton’s NewMedia officers had also been quoted as saying offhandedly that the patent covered “anything on a chip.” This clearly added even more fuel to the fire.

So, to me the biggest fly in the ointment was Frank’s hubris. Frank’s announced desire to be paid a 1% royalty on multimedia sales in the middle of the industry’s biggest conference on newly emerging technology was not just a political misstep, or overreaching, it was nuts.

Unfortunately, the consequent delay in enforcing the Compton’s patent brought about by Frank’s misjudgment is what really killed the patent. The political blowup following Frank’s Comdex declaration caused the Patent Office to promptly pull the patent. This caused a nine-year delay in Britannica being able to enforce what the Patent Office would again find to be a perfectly valid patent. At least one academic study has gone into the details of the Patent Office’s questionable decision to reexamine the patent. Further, the law firm’s technical error that might have been caught and cured early on ultimately led to invalidation of the patent in 2009. This gave way to a further six-year delay pending Britannica’s malpractice case claims against its law firm being finally assessed and turned down by a court in 2015.

The delay was deadly because by 2015, software technology had dramatically advanced in the quarter century since the Compton’s patent application was originally filed. By 2015, everything that was astoundingly novel back in 1989 had not only become commonplace, but it was so old hat that it was not hard for the federal court involved to conclude that the invention was no big deal and merely “an abstract idea.” Also, it was easy for people to surmise that a company founded in 1768 like Encyclopaedia Britannica, a stodgy reference publisher of multi-volume printed encyclopedias, was just not in the right company with the emerging technology giants of Silicon Valley. It was hardly a regular player in the high-tech patent field.

I think there was a good chance Compton’s patent could have had a normal commercial life had not the political uproar at its birth delayed its day in court to a point in time when a usually correctible technical error could no longer be fixed and the substantive patent law had evolved in the meantime to make software patents generally harder to come by.

To my eye, the malpractice court’s conclusion may have saved a local law firm from having to pay for an egregious error, but the way it arrived at this conclusion gave short shrift to the unique contribution Encyclopaedia Britannica had made to the advancement of the human/computer interface.

If Stanley Frank is the fall guy for the story of a fundamental patent that lived and died several times over a quarter century, could there possibly be a hero anywhere in this found-and-lost tale?

Absolutely! Let Harold Kester be given his due. Harold more than any other single person was the true inventor of the breakthrough invention embodied in the Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia. In the long history of the Compton’s patent litigation, neither the Patent Office nor anyone else successfully brought forward prior art that challenged the fact that the invention Harold Kester was central to creating was the very first of its kind. His Del Mar group had been hired by Britannica to provide a search engine for the unusual and novel CD-ROM Britannica was determined to develop, and under Harold Kester’s exceptional leadership, his group, with ESC and Britannica’s editors, accomplished what it was asked to do.

After first learning of the scope of the computer software undertaking being launched, I travelled many times from Chicago to Solano Beach and La Jolla, California, where Harold Kester led the small team that worked on the search engine at the heart of the project. Having watched Harold at white boards leading his team through the analysis of the software’s internal organization, I can personally say Harold was the key genius that could put all the pieces together.

Harold was the mathematical wizard who was able to couple the nascent science of computer search technology with the recent computer hardware advances. Though others were involved on the teams that put his ideas to work, Harold Kester was really the one who can be primarily thanked for the Compton’s innovation.

In recalling this part of the development of the human/computer interface early in the Information Age, I was left wondering what the reaction would have been if Ted Nelson had been able to bring his Xanadu Project to fruition in the form of a similarly novel, functional, and valuable end product. Would people really have thought that the novelty and ingenuity of his hyperlinked product was nothing more than a display of a “fundamental human activity”? Would it have been dismissed as a mere “abstract idea” that had already been floating around for thousands of years. Personally, I think not.

Britannica’s took its final appeal from the adverse decision of its legal malpractice case to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016. The Court has the discretion to hear most appeals, but usually takes only cases of the broadest public consequence or when the lower federal circuit courts of appeal disagree on major issues. In the latter case, guidance from the high court is helpful in bringing consistency in decisions of the lower courts in the future. Although Britannica’s case involved such a split in the lower federal courts of appeal, the Supreme Court chose not to put this particular case on its docket.

If you’re interested in what a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari looks like or are curious about the underlying legal arguments in the case, take a look at Appendix 1 of this book. There you can read excerpts from Britannica’s final and unsuccessful effort to uphold its patent. In an odd result, the twenty-three years of litigation over the patent lasted longer than the normal term a patent remains in effect after issuance.

You may note that Douglas Eveleigh’s name and not mine is on the Supreme Court’s Petition as Britannica’s lawyer. That’s because I had chosen Doug to replace me as Britannica’s General Counsel when I retired from the company two years before the Petition was filed.

A Look Back from Encyclopaedia Britannica

Looking back on my Encyclopaedia Britannica days, when I departed United Press International after its bankruptcy, UPI was fortunately headed towards a reorganization and not a liquidation. Though I had been with UPI only two years, it had directly prepared me for the much more challenging role as Executive Vice President, General Counsel, and Secretary of Encyclopaedia Britannica, as well as my related work as Secretary of Britannica’s owner for much of this time, the William Benton Foundation.

Given that the sole beneficiary of the Foundation for several decades was my alma mater, the University of Chicago, it was particularly gratifying to see that institution enriched in this period by over $200 million in Britannica largesse.

The fulfilling years I spent at UPI and Britannica would never have come about without my first having left private practice for The Bradford Exchange and my first job as a General Counsel. That opportunity gave me the chance to function in a business role as well as a legal role. As time went by, this turned out to be a quite satisfying complement to my previous strictly legal role.

At Britannica I was able to take on the role of a business manager more fully while serving as President of Encyclopaedia Britannica Educational Corporation, and when I briefly headed up another Britannica subsidiary, the premier dictionary publisher of American English, Merriam-Webster.

When Britannica’s CD-ROM encyclopedias began to be counterfeited in China and elsewhere, I had Britannica join the International Anticounterfeiting Coalition, a Washington, D.C., not-for-profit trade association devoted solely to combating product counterfeiting and piracy. The IACC members included a cross-section of business and industry. Including firms such as Ford, Disney, Levi Straus, and Apple, members were involved in selling cars, apparel, luxury goods, pharmaceuticals, food, and software to name only a few of the industries dealing with counterfeiting challenges. After several years serving on the IACC’s board of directors, I was elected its Chairman. In that role, I interacted with law firms, investigative and product security firms, government agencies, and intellectual property associations here and abroad. This function also gave me experience on Capitol Hill lobbying Senators and Members of the House. As IACC Chairman I travelled to Europe, China, Hong Kong before the turnover, and Taiwan urging officials there to strictly enforce their intellectual property laws and to stop the pirating and knockoffs of American products.

In the lobbying and public policy roles that Britannica afforded me, I had a chance to meet at Britannica’s offices with U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin. When I later continued public policy discussions with him in his Washington, D.C., Senate office, I found assisting him at the time was J.B. Pritzker, later the Governor of Illinois.

Britannica also had me separately travelling all over the world dealing with issues at its many international operations. EB did significant business in most of the European countries, as well as Turkey, Greece, Israel, Egypt, Australia, China, Taiwan, Philippines, Japan, South Korea, and India.

Travelling with Frank Gibney, Vice Chairman of EB’s Board of Editors, stands out among all my trips.

Gibney had learned Japanese while in the Navy in World War II and ended up serving in Japan in Naval Intelligence at the War’s end. As a journalist, Gibney had returned to Japan in 1949 as Time-Life's bureau chief, travelling from there to report on events in Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia. After later stints with Newsweek, and as a speech writer for President Lyndon Johnson, he joined Britannica in 1966. In the next several decades he had brought about the publication of local language editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in Japan, and South Korea.

In 1985, Gibney met with Mao Zedong’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, who was putting into practice Mao’s opening of China to the West. The meeting coincided with the launch of the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia in the Chinese language. The attendant global publicity served to announce that with the publication of China’s first non-Marxist encyclopedia, China was opening itself up to the world culturally as well as economically.

It didn’t take long for a Taiwan entrepreneur to counterfeit Gibney’s mainland encyclopedia by using the Mandarin Chinese language characters more commonly read on the island. As a result, I repeatedly traveled to Taiwan in the late 1980s to initiate police raids to seize inventory of the transliteration print set and prosecute local court actions that included an appeal to Taiwan’s Supreme Court. Given the Berne Convention of 1971, Taiwan had clear international treaty obligations to protect EB’s copyright in the work. With this problem persisting, and help from the American Institute in Taiwan, the de facto American Embassy in Taipei, Britannica’s Chief Financial Officer Fred Figge and I secured a meeting with Taiwan’s Vice Premier in 1988, Lien Chan. In our formal meeting, Chan immediately disarmed our aggrieved demeanor. Knowing that Briannica was owned by a foundation that solely supported the University of Chicago, he quickly mentioned that, having a graduate degree himself from the University, he appreciated our concern.

We ended up solving our counterfeit problem and Chan went on to serve as Taiwan’s Premier. Later, he became the first Premier to travel to the mainland in pursuit of better relations. After retiring from politics, like Gibney’s before him, he had his own meeting with China’s leader. For Chan, it was a meeting with Xi Jinping in 2013.

Most memorably for me was heading off with Gibney to the Kremlin in December 1990 in a similar exercise. He and I had previously been involved in long negotiations in Moscow to bring about the first non-Marxist encyclopedia in the Russian language.

As had been true in 1985, when Gibney met with Deng Xiaoping as part of China’s opening to the West, Mikhail Gorbachev was now engaged with Britannica in 1990 in the U.S.S.R.’s own cultural opening to the West.

The upshot of this was that Gibney and I were travelling to Moscow with EB’s Chairman, Bob Gwinn, to celebrate the conclusion of our negotiations with a series of public and private events. As part of the week-long activities, it was agreed that Gibney would write an article for Britannica based on an interview with Alexander Yakovlev, then Gorbachev’s senior advisor.

This was not an easy time for either Gorbachev or Yakovlev, as in 1989 most of the Marxist-Leninist regimes in Eastern Europe had collapsed. Indeed, at the very time Gibney was interviewing Yakovlev in the Kremlin, both Yakovlev and Gorbachev were being denounced by Communist Party hardliners in the Soviet Parliament for “losing” Eastern Europe. Gibney’s unusual meeting in the Kremlin with the architect of Gorbachev’s “glasnost” policy was shortly followed by the hardliners failed coup against Gorbachev, the collapse of the U.S.S.R., the end of the Cold War, and the end of the Russan encyclopedia project.

Apart from the hoopla surrounding the events in Moscow, being doubled up in a scarce hotel room with the endlessly fascinating Gibney was for me in one way memorable in a bad way. As we were leaving Moscow, Gibney complained to EB’s Gwinn within my earshot that he was dead tired and sick of having to put up with my loud snoring all week.

At a 2005 Britannica farewell for Gibney at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute (now the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures) Gibney’s son James, then at the New York Times, remarked about his father’s career problems with authority. A decade later, in 2015, CBS News quoted Gibney’s film documentarian son Alex on his father’s career, “They say to succeed you’re supposed to suck up and kick down. Well, he was the classic guy who sucked down and kicked up, which is never a good career path! He was at Time, then fired. At Newsweek, fired. At Life, fired.”

While I can’t speak to those times, I do remember Frank entering into EB’s Chairman Bob Gwinn’s office at Britannica’s Chicago headquarters several times all sweetness and light, only to emerge and immediately disparage Gwinn behind his back to the first person he bumped into. Though Gwinn was to many a ripe subject for criticism, I can well imagine that this may have been an aspect of Frank’s earlier career modus operandi. Thus, it wouldn’t be surprising to me if some of his previous bosses might have noticed this tendency and concluded Frank was less important to their enterprise than they had previously thought.

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, it’s hard not to conclude that my unplanned departure from Bradford was the best thing that ever happened to me in my working life. After all, had I stayed, I would have missed the great fun of a broad legal and business career. Instead, I would have spent decades in a not-so-interesting professional life as general counsel of a one-time plate company that later expanded into other knick-knacks.