Subchapters

Jane Byrne vs. The Chicago Tribune

The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

Mayor Byrne’s 90-Day Report Card

Mayor Jane Byrne’s Secret Transition Report

Rob Warden

“Innuendo, Lies, Smears, Character Assassinations and Male Chauvinist”

Rally ‘Round the First Amendment

Will She or Won’t She?

The Aftermath—Harold Washington Defeats Jane Byrne

The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

Mayor Byrne’s 90-Day Report Card

Mayor Jane Byrne’s Secret Transition Report

Rob Warden

“Innuendo, Lies, Smears, Character Assassinations and Male Chauvinist”

Rally ‘Round the First Amendment

Will She or Won’t She?

The Aftermath—Harold Washington Defeats Jane Byrne

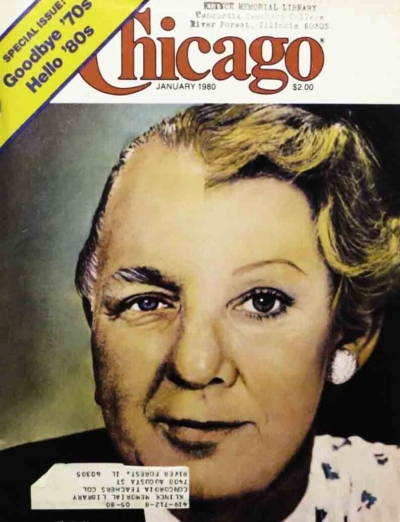

Composite of Mayors Richard J. Daley & Jane Byrne in January, 1980 issue of Chicago Magazine

Chapter 3

Jane Byrne Burned—Chicago Politics in the 1970s

In June 1980, as Jane Byrne was starting her second year as Chicago’s first woman mayor, a strange media brouhaha briefly transfixed the city. She had become enraged at a Chicago Tribune story and in a fit of anger had banned the paper’s City Hall reporter from occupying space in the building’s press room.

The article that triggered her wrath disclosed the details of a transition report she herself had commissioned after she had beaten the remnants of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley’s fabled political machine and secured the nomination of the Democratic Party for mayor in the February 1979 Democratic primary election.

While she had received the transition report shortly after she had won the general election the following April, she and her staff had subsequently kept a lid on it.

The front-page story reporting on the details of the transition report that appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Sunday, June 22, 1980, revealed me to be an author of part of the previously secret report, as well as the immediate source of its startling revelations.

How the report came to light, and my part in it, was a combination of highly unlikely circumstances. However, for all the ensuing media Sturm und Drang of the day, any telling of the story will always seem akin to some like Shakespeare’s Macbeth, just a tale “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” In retrospect, perhaps its only lasting effect was to reinforce the public perception of Jane Byrne as trouble prone, often due to her own devices.

I would never have ended up in the middle of this to-do without the political engagements I had earlier in the 1970s. My involvement in the media train wreck relating to release of the report naturally grew out of my work with two reform politicians on Chicago’s north side, Dick Simpson, and Bill Singer.

Daley was in a race for a sixth four-year term in 1975. Fortunately for him, Singer was not the only candidate running against him.

Helping split the anti-machine vote was the first African American ever on a Chicago mayoral ballot, State Sen. Richard Newhouse. Also in the race was former State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan. Hanrahan was attempting a political comeback following the killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton by police under his control and Hanrahan’s consequent failure to be reelected.

The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

With the anti-Daley vote thus split, Daley was reelected in the Democratic primary election in February 1975 with 58 percent of the vote. Singer came in second with 29 percent, Newhouse with 8 percent, and Hanrahan 5 percent. In a striking change to the usual playing field, Daley’s share of the vote was much smaller than in his earlier races for mayor. And this time, he also won less than half of the African American vote. This portended the fundamental shift that finally occurred when Harold Washington spoiled Jane Byrne’s shot at a second mayoral term and was elected Chicago’s first African American mayor in 1983.

Shortly following Daley’s death in 1976, mourners had an opportunity to pay their respects by passing his casket as it lay in state at the Nativity of Our Lord Catholic Church in Daley’s home ward. An estimated 100,000 came to this church in Daley’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The mourners included political figures such as Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, President-elect Jimmy Carter, and U.S. Senators Edward Kennedy and George McGovern. Those paying their respects also included political opponents. Both myself and my then-brother-in-law Bill Singer stood in the cold in the long line waiting access to the church that day.

Daley’s death was followed by a six-month interregnum during which a number of City Council aldermen jockeyed for supremacy. The upshot was that Michael Bilandic, the 11th Ward Alderman of Daley’s home ward, was elected later in 1977 to fill out the remainder of Daley’s term of office.

Although Bilandic had inherited Jane Byrne from Daley as the city’s Commissioner of Consumer Affairs, she didn’t last long. When Bilandic supported an increase in taxi fares, Byrne not only refused to say it was a needed adjustment, but she also denounced it as a harmful “backroom deal” that Bilandic had “greased.”

That was it for Jane Byrne, who was promptly fired from her job by Bilandic in November 1977. When Byrne announced four months later that she would run for mayor against Bilandic, almost no one took her as a serious threat to his upcoming reelection bid in the February 1979 Democratic primary.

The transition report had been undertaken at Byrne’s request shortly after she defeated sitting Mayor Michael Bilandic in the Democratic primary election in early 1979. A prominent member of her transition team was longtime independent City Council Alderman Dick Simpson. Simpson had graduated from the University of Texas in 1963 and then pursued a doctorate degree with research in Africa. He started a teaching career as a political science professor at the University of Illinois Chicago in 1967, the same year I graduated from the University of Chicago’s Law School.

Off the teaching clock, Simpson became a co-founder of Chicago’s Independent Precinct Organization (IPO) and served as its executive director. The IPO was a body of lakefront liberals focused on good government. In its case, this almost always meant serving as a not-very-heavy counterweight to the dominant machine politics of Mayor Richard J. Daley, head of the Regular Democratic Organization in Chicago’s Cook County. I had gotten to know Simpson from my political work with Singer.

Health had been a minor issue in Daley’s 1975 mayoral campaign and, the year after his reelection as mayor, the 74-year-old suffered a heart attack in his doctor’s office and died on December 20, 1976.

My work on the Singer mayoral campaign had permitted me to get to know Dick Simpson better and, just before Daley died, Simpson told me he was interested in promoting the idea of greater citizen involvement in ward zoning decisions.

He explained how he envisioned community zoning boards might work and asked me to draft an ordinance that would detail their creation, structure, and operation. While I had written plenty of speeches and press releases by that time, I had never taken on the task of drafting a piece of legislation of this complexity. It struck me as an interesting technical challenge, and I told Simpson I’d give it a shot.

This was notwithstanding my own serious doubts about the wisdom of such a radical decentralization of land-use regulation in the city. Then and now, the existing primacy of aldermanic prerogatives in zoning gave aldermen what amounted to a practical veto over many zoning decisions and had engendered widespread aldermanic corruption.

However, it wasn’t clear whether Simpson’s idea was likely to fix that problem or make it worse by encouraging more parochial NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) decisions that shorted the best interests of the city as a whole.

Simpson was pleased with my handiwork and introduced my draft of his ordinance for consideration by the full City Council in early 1977. As was usual with any initiative of one of the independent Democratic aldermen, it was never seriously considered.

I first met Singer in the summer of 1966 after my second year of law school. I was serving then as a summer clerk at the Ross, Hardies, O’Keefe, Babcock, McDugald & Parsons law firm in Chicago. He had already started there as a new associate lawyer recently graduated from Columbia Law School. After my law school graduation in June 1967, I passed the bar exam and joined Singer as a full-time associate attorney at the firm until I entered the Army in May 1968.

Then in late 1968, when Bill learned I was going to be stationed at the Pentagon in Washington, he suggested I look up his wife Connie’s sister, Judy Arndt, then working on one of the Congressional staffs. I took him up on his suggestion. As fate would have it, a few years later Bill and I were briefly conjoined as brothers-in-law. This temporary state soon ended as the two sisters were divorced from the two Bills.

During my time in the Army from 1968 to 1971, Bill had started a successful political career while continuing to practice law. In 1969, as I was settling into my Army work dealing with its newly created civil disturbance mission, Dick Simpson was managing Bill’s winning campaign to be elected an independent Democratic alderman of the 44th Ward in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood.

Later in the decade of the 1970s, the Regular Democratic Organization under Daley had the ward maps redrawn in hopes of squelching Singer’s independent political movement. Nonetheless, Singer was elected in the newly redrawn 43rd Ward and Dick Simpson became 44th Ward Alderman. Both men were constant and articulate critics of the Daley era’s centralized control over the politics of both the City and Cook County. They were up against powerful headwinds, as Daley’s wildly successful patronage-based political organization wasn’t called the “machine” for nothing.

Before I left the Army in 1971, another Ross, Hardies associate, Jared Kaplan, had called me from Chicago to say he was coming to Washington on business and would like to have lunch. I invited him to join me for a sandwich in the Pentagon’s central courtyard, then open to civilian visitors. During lunch, he told me that he, Bill Singer, and some other Ross, Hardies lawyers would shortly be leaving the firm to start a new smaller law firm. He wanted me to join them.

At the time, I was turning 28 and felt that my time in the Army had put me behind my law school contemporaries in pursuing my legal career. Almost all of them had been able to pursue their legal careers without a three-year interruption for military service. At the time, I was having a hard time remembering what if anything I had actually learned in law school. I thought that, though it would be riskier to turn down my standing offer to rejoin Ross, Hardies, joining a startup firm would likely give me more experience and responsibility sooner in the practice of law.

My thinking was that this would also let me catch up to my peers sooner than if I were to go back to a larger, more structured law firm. With the die cast, I left the Army in spring 1971 to practice at the newly established law firm of Roan, Grossman, Singer, Mauck & Kaplan (later Roan & Grossman). Not returning to Ross, Hardies turned out to be fortuitous for me as the firm shortly thereafter was forced to lay off most younger lawyers after its largest client, Peoples Gas Co., decided to fire the firm and create its own in-house law department.

Bill Singer, while 43rd Ward Alderman and a partner at the new Roan & Grossman law firm, had joined with Jesse Jackson and other liberal anti-machine forces to successfully challenge the seating of Richard J. Daley’s delegation of regular Democrats at the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami. This success and attendant publicity led Singer to give thought to challenging Daley in the mayoral Democratic primary race to take place in February 1975. Singer announced his candidacy on October 15, 1973, leaving himself a full 18 months to raise funds and campaign throughout the city.

During this period, Singer asked me to become Secretary of his 43rd Ward organization, and later, as his campaign picked up steam, to join the campaign full time. Being eager to take on the challenge of what I thought was a worthy battle, I took a leave of absence from Roan & Grossman and became General Counsel and Director of Research of the Singer mayoral campaign. As the campaign grew more frantic and Singer’s time got stretched thinner, I also began writing occasional speeches, campaign statements and press releases, as well as position papers on various issues of the day.

During the Singer campaign in 1974-1975, I had met Don Rose, a longtime anti-machine and civil rights activist. Later, in 1979, I briefly sought his advice as I launched an unsuccessful effort to defeat the current machine Democratic Committeeman for the 43rd Ward. I don’t remember the advice Don Rose gave me, but it wouldn’t have mattered one way or the other.

As it turned out, I was tossed off the ballot for having insufficient signatures on my nominating petitions. I successfully appealed this decision of the Cook County Board of Election Commissioners, and the Illinois Appellate Court ordered my name back on the ballot. However, when the dust finally settled, I could tell people I’d lost the election by only seven votes. Unfortunately, these were the votes of the seven Illinois Supreme Court justices who reversed the Appeals court. Thus, was short-circuited my ill-fated political career.

Though usually working behind the scenes, over the years Rose had a number of important roles in the city’s electoral contests and political spectacles. In 1966, Rose had served as Martin Luther King Jr.’s press secretary when King moved into a Chicago slum to bring attention to poverty and racial injustice in the North as part of his Chicago Freedom Campaign. Apart from handling the local press in this effort, Rose served as a King speechwriter and one of his local strategists. He later looked back on this effort as probably the most important thing he ever did.

Two years later in fall 1968, Rose had a major role in the circus around the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The resultant street battles with police immediately preceded the opening of the Democratic National Convention. The following year, my law school classmate Bernardine Dohrn and her fellow radical, Bill Ayers, were busy organizing the Days of Rage riots of the Weather Underground. I was watching all this unfold with more than casual interest given my role at the Pentagon at the time in assessing whether civil disturbances might grow.

Coincident with the Convention unpleasantness, the “Yippies” had also arrived in Chicago for the Convention with their political theater of nominating a pig for president. However, SDS and the Yippies were just the opening act in 1968. The bulk of the anti-war demonstrators had come to town by the thousands under the aegis of the coalition of groups known as the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam; the MOBE for short. And Don Rose, building on his recent successful effort for Dr. King, became the press spokesman for the MOBE and was credited with creating the slogan of the anti-war demonstrations, “The Whole World is Watching.”

A committed man of the left all his life, Rose could manage to work for a Republican if the times called for it. He took particular pride in his management of the campaign of Republican Bernard Carey in 1972 against the sitting Cook County State’s Attorney, Edward Hanrahan. Hanrahan had been vastly weakened with the public as a result of his deadly raid on Black Panther leader Fred Hampton’s house in late 1969. Most people thought the raid was a botched one at best and a murderous one at worst.

I personally felt so strongly about it that I and Ross, Hardies lawyer Phillip Ginsberg had earlier called upon the Chicago Bar Association to initiate a breach of legal ethics investigation against Hanrahan.

Notwithstanding the Hampton scandal, when Hanrahan came up for reelection, he was still the machine candidate and widely presumed to be a winner. That’s when Don Rose arrived and helped Carey win what would normally have been a losing matchup.

Chicago Tribune contributing Sunday editor Dennis L. Breo captured a profile of Rose in a 1987 portrait. When I recently reread the article, I was struck by the fact that I had a relationship of one sort or another with all of those he quoted talking about Rose. Basil Talbott, political editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, was a friend I knew from politics and Lincoln Park, Mike Royko of the Chicago Tribune had written a column about my uncle, Judge Augustine Bowe, when he died. Also, as a widower Royko had later married my first wife, Judy Arndt. Ron Dorfman was a friend and the journalist who founded the Chicago Journalism Review in 1968. At the end of his life, he beat it to death’s door by becoming half of the first gay couple to marry when Illinois law changed in 2014. The last to be quoted was my former law colleague and brother-in-law, Bill Singer. While I was only casually acquainted with Rose, we had many other friends in common.

With a long history of civil rights and anti-Daley, anti-machine credentials, Rose again was available for a battle against the machine in 1979 when Jane Byrne looked to all like a quixotic loser up against Daley’s successor Bilandic.

Mayor Byrne’s 90-Day Report Card

In the 1975 Democratic primary election for mayor, the Chicago Tribune had taken a pass on the endorsement of any of the candidates, saying it was a question of, “whether to stay aboard the rudderless galleon with rotting timbers or to take to the raging seas in a 17-foot outboard.” By the time Don Rose joined Byrne to manage her campaign, the “rotting timbers” of the Democratic machine had more completely eroded. And the former Commissioner of Consumer Affairs, Jane Byrne, not only had the temerity to run against the machine’s choice for mayor, but she also had a tough, down-to-earth, scrappy personality that sharply contrasted with her reserved and bland opponent.

The longtime liberal lakefront constituency in the city’s 5th Ward in the University of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, and more recent independent north side lakefront wards represented by Simpson and Singer, solidly backed her. She also benefited from the growing opposition to the machine in the Black community.

But what really put her over the top was the 35 inches of snow that fell in the two weeks before the February 27, 1979, primary election. It had been met with a perceived collapse of the city’s usually more efficient snow removal efforts. The primary ended with Byrne garnering 51 percent of the vote and Bilandic 49 percent.

Mike Royko’s Chicago Sun-Times column immediately declared that, amazingly enough, ordinary Chicagoans had decided to finally defeat the machine. He thanked those who voted for her and said, “today I feel prouder to be a Chicagoan than I ever have before in my life.”

Not long after Jane Byrne was elected mayor in the April 1979 general election, I wrote an article for the August 1979 issue of Chicagoland Magazine assessing her first three months in office.

In the course of my review of her early performance in office, I first took a look at the broader context of the changing politics of Chicago from which she had emerged. For Richard J. Daley, the 1970s had been the most difficult period of his decades-long domination of the city’s politics, and the grand patronage machine he had fine-tuned was substantially weakened by the time he died in 1976. Throughout the 1970s, the growth of independent opposition continued, as did disaffection in the Black electorate.

As my article below reminds me, the beginning of Jane Byrne’s mayoralty exposed the very seeds that would grow in the succeeding years and deny her reelection in 1983:

It cuts, it chops, it whirls like a dervish. It spins, it dices, it reverses direction as fast as A. Robert Abboud. It makes mincemeat out of dips with a mere flick of the tongue. It likes to really mix it up. A revolutionary new food processor you ask. Not at all. It’s La Machine—By Byrne.

If Daley was the Machine’s Christopher Wren, Bilandic was its Cleveland Wrecking Company. Through the sheer force of his impersonality, he systematically and devastatingly eroded the public perception that somebody was in charge and in control of a very large, very rough and tumble city.

And, in fact, he wasn’t in charge, having delegated the politics of the job to Daley’s unelected former patronage functionary, Tom Donovan. As Chicago Byrned, Bilandic fiddled: jogging, raising cab fares and cooking on Channel 11. Or so it seemed.

It was all too much for the neighborhoods, no matter what the precinct captains said, the one thing most folks out there realized was that if they didn’t take charge of the operation for once and put a tougher person in that office on the 5th Floor, they’d be snowed-under, potholed, garbaged, and maybe even thieved to death. Irony of ironies that the City of the Big Shoulders put a diminutive politician in high heels in charge of the store and relegated the male incumbent to the relative quietude of a law practice on LaSalle Street. The fabled “Man on Five” became transmogrified into the “Women on Five” and in Chicago no less!

Clearly Byrne had one of the fastest mouths east of Cicero. But would her kind of instinctive, politically combative, hip shooting translate well once the substantive issues came along? A bit of evidence is now in and the answer to that question is something of a mixed bag. She hasn’t proved it yet, but at least it appears Chicago has a mayor again. Take three issues that emerged early on: appointments, condos and the Crosstown ….

Mayor Jane Byrne’s Secret Transition Report

Because Byrne had run as a reform candidate, after the primary election she quickly sought advice from a panel of knowledgeable experts pulled together for a transition team headed by a Northwestern University professor, Louis Masotti.

Masotti had taken a leave of absence from the University’s Center for Urban Affairs and in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, said that the team’s transition report for the new mayor was designed “to assist a fledgling administration to hit the floor running.”

Masotti went on to say of his 26-member transition committee:

What we did was not budgeted; nobody got paid. We had no staff. These were citizens who at the request of the mayor volunteered to spend a hell of a lot of time and energy and put their reputations on the line to provide information to help guide the mayor.

The fact that she chose to dismiss it, apparently without reading it or judging it on its merits, was not well received by anyone on the committee. Nor did anyone get any appreciation in any way, shape, or form, including me.

Dick Simpson was the principal author of the report, New Programs and Department Evaluations. The document was reported to be 1,000 pages long, 700 of which were made available to the Tribune. Other transition team members besides Simpson included Bill Singer, Leon Despres from the 5th Ward in Hyde Park, and other well-known opponents of the Regular Democratic Organization. When the Chicago Tribune story on the transition report broke, it had a sidebar by George de Lama and Storer Rowley noting that I had written a section of the report.

Years later, I don’t recall what part it was, but it may well have dealt with the Chicago Public Schools. I had spent a good deal of my time on CPS matters in my Director of Research role in the Singer mayoral campaign. Singer had made improving the public schools the centerpiece of his mayoral campaign, and I had ended up writing most of the lengthy policy study the campaign released. When Jane Byrne went on to win the general election in April 1979, she corralled 82 percent of the vote in defeating Republican Wallace Johnson. Shortly thereafter, she and her staff received Masotti’s transition report. The decision was quickly made to keep it under wraps.

Rob Warden

I had met journalist Rob Warden both through my law practice, and separately knew him from frequenting Riccardo’s bar after working hours.

Warden was a former foreign correspondent in the Middle East for the Chicago Daily News and had become editor of the Chicago Lawyer after the Daily News folded in 1978.

The magazine had been started by lawyers unhappy with the media coverage of the profession, and they wanted the available Warden to improve press coverage of the judicial selection process. Warden being Warden, Chicago Lawyer had quickly moved on to subjects of broader public interest, including prominent lapses in legal ethics, non-legal governmental processes, and police misconduct. Warden in later years would document with James Tuohy Chicago’s Greylord scandal of widespread judicial bribery and end his career in 2015 as Executive Director Emeritus of Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law’s Bluhm Legal Clinic Center on Wrongful Convictions.

Warden and I liked and respected each other and, as editor of Chicago Lawyer, he had commissioned recent articles I had written for him on the proliferation of foreign bank offices in the city and the messy transition leading to banker A. Robert Abboud heading up the First National Bank of Chicago.

Unhappy with the transition report being bottled up by Byrne, Warden had brought suit against the city for its release. In December 1979, Cook County Circuit Court Judge James Murray ordered that the six-volume report see the light of day.

However, with the city appealing the order, the report was still out of sight a year after Byrne’s election. That was when, on June 6, 1980, Warden and Dick Simpson arranged for a copy of the report to be offered to the Chicago Sun-Times in a manner that would enable it to gain a major competitive scoop over its great rival, the Chicago Tribune.

Simpson’s goal in taking the still-secret report to the Sun-Times was primarily to bring to light the report’s many recommendations to reduce government waste. Along the way he also hoped to generate some publicity for a forthcoming book he had edited that contained a long essay developed from the report. Because the Chicago Lawyer had been responsible for successfully suing the city to release the transition report, Simpson wanted to let Warden and the magazine publish its own account of the transition report coincident with the Sun-Times. Apparently, the Sun-Times was agreeable to this general arrangement.

An article in the Chicago Reader later described the press brouhaha attending the revelation of the transition report as a “tale of life on Media Row—a tale of misspent passions, split-second decisions, and late-night cloak-and-dagger.”

When Simpson gave Warden a copy of the 700 pages in his custody, Warden passed it on to me and asked me to digest the tome in an article appropriate for Chicago Lawyer readers.

I had read the entire report in my Lincoln Park home by Friday, June 20, and had just begun to write my article. Some time on Friday, Warden heard that the Sun-Times was at that moment putting together a three-part version of its story and planned to publish it in final form beginning in that Sunday’s paper.

Warden promptly called the Sun-Times Editor, Ralph Otwell, to see if he could delay the Sun-Times’s publication long enough for me to finish my article and have it ready for publication in Chicago Lawyer at roughly the same time as the Sun-Times would publish. According to the later Chicago Reader article, Otwell said the story was already in the paper, but he’d see if he could delay it. In fact, Otwell was able to delay it and the first edition of that Sunday’s Sun-Times had nothing about the transition report.

About 11 that Friday evening, Warden was at Riccardo’s, a favorite media watering hole, when a Sun-Times editor, unaware of Otwell’s success in delaying publication of the article, told Warden the article had been set for publication in Sunday’s paper.

At the time, I was newly married and my wife, Cathy, was pregnant with our first son, Andy. We were living in a townhome on Larrabee Street in the Lincoln Park neighborhood when I shortly got an unexpected telephone call from Warden.

He said the Sun-Times had jumped the gun on its article, and with the timeliness of the Chicago Lawyer’s article now undercut, he wanted to give the Chicago Tribune immediate access to my copy of the report. He asked me to also lead the reporters who would write the front-page story for the Tribune’s Sunday paper through the lengthy document.

This would be necessary for such a complicated story given the tight deadline, but achievable given the fact that I had already carefully analyzed it for its newsworthy elements and had already formed my own idea of how the article might be structured.

Warden told me I was to stay awake and await the arrival of two reporters.

At precisely 1 a.m. Saturday, my doorbell rang, and George de Lama and Lynn Emmerman from the Tribune arrived, ready to jump into their task with both feet. As they entered, de Lama handed me a handwritten note Warden had given them testifying to their bona fides. It read:

The Tribune reporter who has this note has my blessing. The Sun-Times is screwing us on the release of the transition Report. I’d like to read it in the Tribune first. Help them.—Rob

I led de Lama and Emmerman through the hundreds of pages, explaining the structure of the report and pointing out for them what I thought to be the more important and interesting critiques of the various City Departments. I also reviewed with them the pertinent recommendations that had been made to the incoming mayor. It was 5 a.m. before we had gotten through it all, at which point my visitors left. Their next task was to quickly write up their lengthy story and accompanying sidebars and meet the Saturday deadline for the early edition of Sunday’s paper.

“Innuendo, Lies, Smears, Character Assassinations and Male Chauvinist”

The upshot of this frantic deadline mission was that the early editions of the Sunday Tribune that hit the streets Saturday evening had the story blasted over its front page and spilling into multiple inside pages, and the Sun-Times didn’t. The Tribune’s headline screamed, “Secret City Report Cites Waste, Incompetence.” The lead (or “lede” for nostalgic romanticists of the linotype era) of the story on page one was a classic:

Exclusive report: A SECRET evaluation of the City of Chicago prepared for Mayor Byrne last spring at her request by a hand-picked team of advisers and later shelved by her administration found widespread waste and incompetence in the city government she inherited. The secret report, obtained Saturday by the Tribune, was apparently ignored, however, as the mayor and top officials of her administration deemed its recommendations for a general overhaul of the city’s governmental structure and the dismissal of several clout-heavy department heads politically inexpedient.

When the Sun-Times’s Otwell saw that his paper’s exclusive had gone out the window, with the story already written in house, he was able to promptly recover and feature it on the front page of the later Sunday edition of the Sun-Times. Proving the adage that when it rains, it pours, both the Tribune and the Sun-Times had been gifted a new story element by Mayor Byrne. Splattered across the top of its later Sunday edition, the Tribune headline read, “Tribune barred from City Hall: Byrne.” The story lead explained:

Within hours of a published report critical of the way the city was run prior to her administration, Mayor Byrne called The Tribune city desk Saturday evening and said she would throw the paper’s reporters out of City Hall Monday morning. “Today’s paper was the last straw, “she said. “Your paper will not have privileges at the City Hall press room. Never again will I respond to reports in the Chicago Tribune.”

The shocking new story line immediately seized the attention of all Chicago’s media as the television news departments now jumped into the mix with fevered stories and speculation on the imminent death of the First Amendment and the Mayor’s ongoing predicament of how to walk back her untenable promise.

The late edition of the Sunday Sun-Times also prominently featured the Tribune’s ouster and reported that a statement released by Byrne’s press secretary and husband, Jay McMullen, to the City News Bureau said, “The Chicago Tribune has engaged in innuendo, lies, smears, character assassinations and male chauvinist tactics since Jane Byrne became mayor.”

Byrne added in an interview with the Sun-Times that the Tribune articles were but the latest in a long series of unfair attacks on her administration.

She called the task force’s findings “ridiculous,” the Tribune’s reporting, “yellow journalism,” and said that the newspaper “only printed 85 percent of the story.” The Sun-Times story went on: The mayor said she would refuse to answer any questions posed by Tribune reporters and would refuse to comment to other reporters on stories carried by the newspaper. She also repeated directly to the Sun-Times, “I will never, ever talk to them [the Tribune] again.” She also dismissed the advisory study itself as “unbelievable, naïve and superficial.”

Rally ‘Round the First Amendment

Sunday morning, husband Jay McMullen spoke to Bob Crawford, longtime City Hall correspondent, on WBBM radio. When Crawford raised the question of the mayor being sued and losing, McMullen opined, “At least we will have made our point.”

McMullen also went on offense by telling the United Press International wire service, “Let them sue; we’ll take it all the way up to the Supreme Court.” (Though I wasn’t General Counsel of United Press International for another five years, I can’t help but think I would have been filing a friend of the court brief siding with the Tribune if such a lawsuit had come to pass in later years.)

The American Civil Liberties Union, which then enjoyed a reputation for defending free speech, found the Byrne action “outrageous” and predicted her Tribune ban would not be upheld even if taken to the Supreme Court.

Stuart Loory, president-elect of the Chicago Headline Club and managing editor for news of the Sun-Times, found a “clear violation” of the First Amendment.

The Chicago Newspaper Guild union was equally aghast, “We vigorously and unanimously condemn the mayor’s action.”

Sun-Times publisher James Hoge chimed in, calling the ban “indefensible.”

Will She or Won’t She?

At first, this was all taken very seriously. Tribune Managing Editor William Jones said in Monday’s Tribune:

There is no vendetta and the mayor knows it. The Tribune will continue to publish the news without first seeking approval from the city administration. Mayor Byrne is saying in effect that when she disagrees with what is published in the Chicago Tribune, she will take action to impede the free flow of information from City Hall to the people of Chicago. That’s a frightening point of view on the part of any public official. It’s particularly chilling when it becomes the publicly stated policy of the Mayor of the City of Chicago. The issue is not a free desk at City Hall. The issue is freedom of the press.

At the Sun-Times, Byrne’s attack on the Tribune carried over to its own front page on Monday, when the paper’s headline read, “Byrne blames ‘vendetta’ on failure to OK land deal.” The related article by Sun-Times reporter Michael Zielenziger reported that Mayor Byrne believed that the Chicago Tribune’s “vendetta” against her administration stemmed partly from her failure to quickly approve a 54-acre real estate development along the Chicago River east of Tribune Tower.

The land being referred to was owned in part by the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Dock and Canal Co. The latter concern was a 123-year-old company started by Chicago’s first mayor, William B. Ogden. Byrne said she was offended because detailed plans for the proposed development had been presented to her by an officer of the Dock and Canal Co. the preceding Thursday, without first being presented to the city Planning Commissioner.

Left unreported was the fact that the mayor’s occasional spokesman and husband, Jay McMullen, was currently on leave from his job as a Sun-Times reporter on the real estate beat.

With Byrne having thrown down the gauntlet by repeatedly saying the Tribune would be banned from City Hall, the question on everyone’s mind was whether the mayor would actually carry through by kicking the Tribune’s City Hall correspondent out of the building and keep her promise to “never again respond to reports in the Chicago Tribune.”

At the time Roger Simon was making his chops as a reporter at the Sun-Times. He would later move on to be the Tribune’s White House correspondent, and in time the chief political correspondent for both Bloomberg News and Politico. Simon was given the assignment to freely ponder the seeming seriousness of the whole Byrne ban on the paper’s front page. In a series of straight-faced pinpricks, he successfully punctured the dirigible of hot air hanging over the city that morning.

The headline of Simon’s story read, “Trib-ulations make the mayor erupt.” The lead that followed gave more than a hint that everyone should relax and take a deep breath:

Mt. St. Byrne erupted over the weekend, spewing forth steam, hot air and volcanic anger. Mt. St. Byrne, otherwise known as Jane Byrne, mayor of Chicago, was angered when the Chicago Tribune printed a year old report stating that past mayors often were influenced by politics in running the city …. The real question, however, was why Byrne was so mad at the printing of the report, since the report did not attack her, but her predecessor, Michael Bilandic, a man the mayor has often compared unfavorably to a sea bass….

The mayor’s husband, press secretary and chief enforcer, Jay McMullen, immediately sought to calm the situation by announcing that the Tribune would also be barred from speaking to City Hall officials and examining public records. When persons pointed out this might violate the Bill of Rights, Jay was momentarily silenced as he tried to find out if City Hall owned a copy.

Simon concluded his observations with suggestions on how the Tribune might better have responded to the mayor’s attacks and expressed the depressing thought that the city would remain captive to the chaos for the foreseeable future:

But the Tribune is being really dumb about this whole thing. Instead of issuing swell sounding statements about a free press, here’s what I would do: I’d get my five fattest reporters and have them sit on the desk in City Hall. I’d force McMullen to cart it out with a forklift. Then I’d sell the picture to Life Magazine for $10,000. Or I’d get all my editors and have them sit down on the floor of the City Hall press room and go limp. Then when the mayor ordered the cops to move in with cattle prods, I’d have all the editors sing “We Shall Overcome” and sell the soundtrack to “Deadline U.S.A.”

I think the whole affair has been terrific. It’s the most fun the press has had since the Democratic Convention of 1968. During most June days, other newspapers around the country have to write stories about kids frying eggs on sidewalks and flying saucers landing in swamps. But not in Chicago.

We have daily eruptions to keep us busy. I say: “Keep it up, Mayor!” Who cares if those drab little men on Wall Street keep getting upset with all the crises on this city and keep lowering our bond ratings? Those guys have no sense of fun.

As for the rest of you citizens, I realize it sometimes depresses you that Jane Byrne has created all this chaos in just over 14 months.

But what can you do about it? That’s the way it is, on the 434th day of captivity for the hostages in Chicago.

The Aftermath—Harold Washington Defeats Jane Byrne

On Saturday, June 27, just one week after the Tribune laid out the details of the previously shielded transition report, it was left to the Hot Type section of the Chicago Reader to try to pick up the pieces. The very last word, if not the last laugh, was had the next day by the Near North News, one of the Lerner Newspapers.

In the Reader’s analysis, Warden was a former Daily News man with no love lost for Field Enterprises, the owner of the Sun-Times. As a result, he had no trouble believing it when a Sun-Times editor told him of seeing page proofs of the Sunday story and also concluded that Ralph Otwell had failed to pull the story and was going back on its arrangement with Dick Simpson. The Reader reviewed the bidding:

So, to retaliate, Warden decided to turn the Sun-Times’s “exclusive” into no exclusive at all. By midnight, Warden was in the Tribune city room; by 1 AM Saturday, a couple of Tribune reporters had awakened William Bowe, who was analyzing the transition report for Chicago Lawyer, and who (at Warden’s suggestion) led the reporters through its 700 available pages over the next three hours. By 5 AM, the Tribune was assembling an unexpected front page for Sunday’s paper and remaking its “Perspective” section to accommodate a lengthy scorecard of the report’s findings.

The Reader article concluded by quoting Otwell as saying under normal circumstances, the story wouldn’t have been played up as big as it was under a Sunday banner headline. Otwell observed, “After all, it’s a recycled story that wouldn’t seem to justify the space and fanfare that either of us gave it, quite frankly.” When Warden was asked by the Reader if he would have run my story on the front page of Chicago Lawyer, he answered, “Hell no!” The Reader summed it up this way:

At any rate, consider the real meaning of the whole ridiculous episode: (which has probably set back any serious scrutiny of the transition report by months) a year-old story becomes a three-day, three-ring media circus, thanks to one overprotective magazine editor, two contentious dailies, and the city’s dizzy first family. And for a few moments, all of Chicago was fooled into thinking something important had happened.

The truly last word came the day after the Reader’s story and appeared in a regional edition of the Lerner Newspapers, the Near North News. True to its traditional concentration on its local circulation, it focused on the north side addresses of Rob Warden and me before turning to the fact that the Lerner papers had long before run a detailed story on the transition report in November 1979:

Near north siders were heavily involved in the Chicago Tribune story that so miffed Mayor Jane Byrne that she announced the paper was going to be thrown out of City Hall. The mayor’s transition report was obtained by the Chicago Lawyer, edited by Rob Warder, 1324 N. Sandburg. Warden turned it over to Atty. William J. Bowe, 2044 N. Larrabee for analysis. Bowe turned it over to the Tribune. Ironically, the report was printed in great detail last Nov. 18 by the Lerner newspapers, without unduly irritating the mayor.

My own view is that what went on was more than a tale almost about nothing, and that there is at least one solid truth to be unraveled from the affair. This particular media circus added to an already growing view that Jane Byrne, for lots of reasons, was not well suited to serve a second term as Chicago’s mayor. The strange media flap over the transition report and the coverage of her temporary sojourn in the Cabrini-Green housing project conveyed a sense of her instinct for the capillary instead of the jugular. Her firing of officials throughout the city government seemed too disruptive and haphazard to be treated as fair political retribution. Having campaigned as a reformer against the “evil cabal” in the City Council, she had also alienated Rose and other independent-minded supporters when she cozied up to heavyweight machine aldermen like Edward Vrdolyak and Edward Burke. Finally, Chicago was in any event getting ready to move on to the next new thing, the election of Harold Washington, the city’s first African American mayor. While there was much to admire about Jane Byrne personally and her one term as mayor, on balance she added, instead of subtracted, to the city’s ongoing sense of unease after Daley’s long rule, and voters punished her for this at the next election.