Subchapters

- Riots & Rockets Army Days Map (1968-1971)

- Family in the Military

- The Vietnam War Heats Up

- The Decision to Enlist

- Fort Holabird and Intelligence Training

- CIAD in the CD of OACSI at DA in DC

- The Vance Report

- Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations

- Bernardine Dohrn-The SDS Revolutionaries Then and Now

- The Army Operations Center (AOC)

- The Blue U and CIA Training

- The Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System

- Huntsville, Alabama, and the Army Missile Command

- NORAD and Cheyenne Mountain

- Johnston Atoll and the Origins of Space Warfare

- Kwajalein Atoll—The Ronald Reagan Missile Test Site

- Kent State University and the Aftermath

- Yale, The Black Panthers, and the Army

- The Secretary of the Army’s Special Task Force

- Getting Short—The 1971 Stop the Government Protests

- 1974 Congressional Hearings on Military Surveillance

- Lunch with Gen. William Westmoreland

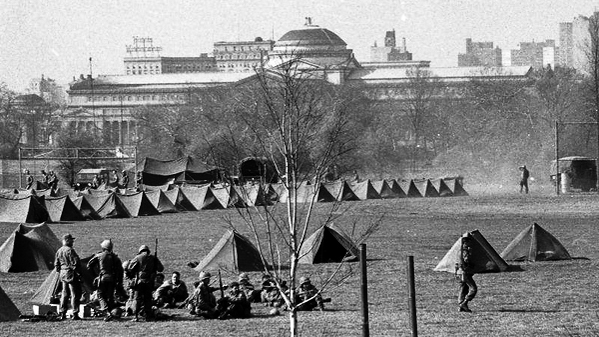

1968 Regular Army troops in Jackson Park, Chicago during riots after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination

Chapter 1

Riots & Rockets—Army Days (1968-1971)

After Army Intelligence School training at Fort Holabird in Baltimore, I was assigned to the 902nd Military Intelligence Group. Its headquarters occupied office space above stores in a Bailey’s Crossroads, Virginia, strip mall.

My Counterintelligence Analysis Division work in the 902nd was at first in converted warehouse space nearby in Bailey’s Crossroads. Later I had office spaces in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff of the Pentagon, the newly built duplex war room called the Army Operations Center, and the Hoffman Building in Alexandria, Virginia. For several weeks in 1969, I also attended a CIA school in a building in Arlington, Virginia, then known as The Blue U.

My living arrangements were first in an Annandale, Virginia, apartment with two 902nd roommates, and then on my own in a Capitol Hill apartment in the District of Columbia. Throughout, I was technically assigned to Fort Meyer, just to the north of the Pentagon.

Family in the Military

My enlisting in the Army during the Vietnam War years was in part influenced by my knowledge of other family members who had served in the military.

Both sides of my family had members in the military. My mother’s grandfather, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Sr., lived in Covington, Georgia, and served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Among my mother’s family memorabilia was a picture of him decked out in his uniformed regalia.

In my immediate family, my father, William John Bowe, Sr., enlisted as a part-time soldier in the Illinois National Guard shortly after graduating from Loyola University law school in Chicago in 1915. He trained at Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois, before the U.S. entered World War I. In time he became a supply sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps. When President Woodrow Wilson called the National Guard into federal service to fight in World War I, a massive influx of draftees came into Camp Grant for training. The camp exploded in size, and in short order my father went to France with the other doughboys. Not long after his arrival in France, while trying to board a moving troop train, he slipped, and his left foot was run over by the train. The good news was that he never made it to the front, but the bad news was that he did make it to French hospitals in Blois and Orleans. The amputation of part of his foot required a long convalescence, and the war was over before he could get home.

The summer of 1967, right after my law school graduation, the young French hospital nurse who had cared for my father in Orleans came to Chicago for a visit. She missed seeing her former patient, as my father had died in 1965. Nonetheless, my mother, my brother, Richard Bowe, and I had a pleasant moment as Mme. Marie Loisley reminisced about that time in the Great War.

As a young child in the 1940s, I, of course, noticed his stump and the fact he was missing his toes on one foot. When I got older, I asked him about it. He answered in a matter-of-fact way and showed me the lead insert he wore in one of his high-topped laced shoes and explained its purpose. He also let me play with his cane without complaint.

In the early 1950s, as my father entered his sixties, his cane had fallen into disuse and largely remained in an umbrella stand inside the front hall closet. Perhaps it was because he was no longer out and about as much. But later in the 1950s, as I was going through high school, it certainly reflected the inexorable progress of his Alzheimer’s disease and its accompanying dementia.

When World War II came along, my Uncle John Dominic Casey, recently married to my mother’s sister Martha Gwinn Casey, also served in the Army. As a child I remember visiting my Uncle John when he was recuperating from a broken leg at a military hospital in Chicago at 51st Street and the lake. After the war, the building served as the 5th Army’s Headquarters before the command was moved in 1963 to Fort Sheridan just north of the city.

In the mid-1950s, my older brother, Dick, was in the Army’s Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) in high school and, like his father before him, later enlisted in the Illinois National Guard.

While my father had caught World War I, Dick was luckier. He was too late for the Korean War and too early for the Vietnam War. Between Dick and my father, it appeared to me that wars of one sort or another tended to engage American men each generation.

However, as I turned 18 and headed off to college in 1960, I thought it unlikely that I would have to follow in either Dick or my father’s military footsteps.

The Vietnam War Heats Up

As I started college in the fall of 1960, I just wasn’t prescient enough to see that, like my father and brother, I also would indeed enter the military. While the Vietnam War ended with a bang with the fall of Saigon in April 1975, it had started with a whimper in spring of 1961, just as I was finishing my freshman year at Yale. That was when President John Kennedy ordered 400 Green Beret Army soldiers to South Vietnam as “advisers.”

Then, in August 1964, after my Yale graduation, but before I started law school at the University of Chicago, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This came in the wake of an apparent attack on the USS Maddox off Vietnam. It authorized the president to “take all necessary measures, including the use of armed force” against any aggressor in the Vietnam conflict. Shortly thereafter, in February 1965, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the bombing of North Vietnam, and the U.S. was in the war big time. I was just halfway through my first year of law school.

After World War II, the draft structure to meet the country’s military needs had been left in place. Thus, it was ready to be employed in my era when volunteers no longer met the needs of the services. Indeed, the draft was increasingly relied upon as the U.S. deepened its involvement in Vietnam. But during the Vietnam War years between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. military drafted only 2.2 million men from a large pool of 27 million. With less than 10 percent of those eligible for the draft being called up, and the lottery mechanism to choose them not put in place until 1969, the question of who got drafted was left up to local draft boards and their use of an elaborate system of draft deferment categories.

Being in graduate school at the time automatically removed the risk I would be taken into the military involuntarily prior to my graduation. After graduation, I’d be single and only 25. Unless I married and had children before I reached the safe harbor of 26, there was a real possibility that I could be drafted.

What to do? I had no desire to marry at that time, and a similar desire not to be killed in Vietnam War. This wasn’t an entirely irrational fear, as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., lists more than 58,300 names of those killed or missing in action. Though my personal odds of being cut down might have been small, the threat did loom large in my thinking. The off chance of catching an errant bullet in an inhospitable place far from home was simply not on my young man’s to-do list.

The Decision to Enlist

While I had no desire to be drafted, I was not adverse to military service. Both my father and brother had entered the military as volunteers. They both seemed proud to have stepped up in the service of their country. I also thought if I weren’t killed, I might enjoy the military or at least gain valuable experience of some sort. Having watched my Uncle Augustine Bowe enter public life as a judge late in life and seem to enjoy it, I also thought Army service such as my father’s or Dick’s couldn’t hurt if I later wanted to pursue that path in some fashion. In my third year of law school, I had unsuccessfully applied for a direct commission as an Army officer. While these half-in, half-out alternatives were not remotely appealing choices for me, as I waited for that process to run its course, the Army Reserve and National Guard openings for enlisted men grew far and few between.

With the draft and these military service options off the table for one reason or another, I graduated from law school in June 1967 at the age of 25 and started working at a downtown Chicago law firm. Among other clients, the firm represented Northwestern Railway and various gas and electric utilities. The mid-sized Ross, Hardies, O’Keefe, Babcock, McDugald & Parsons had its offices in a National Register of Historic Places classic. The building was architect Daniel Burnham’s 21-story, 1911 Beaux-Arts building at 122 South Michigan Avenue, just across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago.

During law school, I had bypassed living in Hyde Park near the University of Chicago to help my mother care for my father in his declining health. He had died halfway through my time in law school, so after graduation I left my widowed mother and moved into the Hyde Park apartment of my college and law school friend Bob Nichols. I traveled to my new lawyering job on the Illinois Central commuter train from the 56th Street Station in Hyde Park to the Van Buren Street Station by the Loop. That left me a short walk to the Ross, Hardies office.

The main military option that still seemed open to me, in this period, other than the draft, was to enlist in the military in a way that might improve my odds of living long enough to get discharged. If I didn’t enlist in the military in the ensuing year, and got drafted as a result, it would most likely mean service in the Army’s infantry, and I’d be out of the military in only two years. A big negative of the draft was that I’d be out even earlier if I were killed in Vietnam.

Of course, why didn’t I think of it sooner?! Forget joining the military the way my father and Dick did. Instead of the Army or National Guard, join the Navy or Air Force. Or better yet, join the Army, Navy, or Air Force as a lawyer. I was pretty sure those folks weren’t getting killed much in Vietnam. With a law degree and admission to the Illinois bar in hand, I could enter the Judge Advocate General branches as an officer and gain directly pertinent experience for my chosen profession.

The unappealing part of this choice for me was the time commitment. With demand high to stay out of the infantry, these slots typically required a minimum four-year commitment. The other problem I had with being a military lawyer was the great danger I saw of being bored.

The possibility of being assigned to spend several years of my life defending or prosecuting AWOLs, handling damage claims brought about by tanks taking too wide a turn, or otherwise spending my time on mind-numbing tasks, was completely abhorrent to me. My solution to this quandary, six weeks before I turned 26, was to enlist for three years in the Army Intelligence Branch on May 13, 1968.

Like all recruits, I was going off to Basic Training that day. Seriously hung over from a farewell party thrown by friends the night before, I was dropped off that morning at 6 a.m. at a large yellow brick building west of Chicago’s Loop. Later converted into a headquarters for Tyson’s Chicken, this was the same building where I had recently had the physical exam that found me qualified to enter the Army. That was literally my first exposure to Army life. I was required to strip off my clothes and walk naked single file with dozens of other men along a painted line that wove up, down and around two floors. Sprinkled along the painted line were way stations for you to pause at for various intrusive inspections of your body. To this day, I remember the impolite request barked at the most humiliating stop, “BEND OVER AND SPREAD ‘EM.” This experience gave me a better understanding of how those Tyson chickens must feel as they head down their own conveyer line of peril.

Bused to O’Hare International Airport, we were flown to St. Louis, and then bused from there to Fort Leonard Wood in central Missouri. I, and the other recruits I had been batched with, got off the buses and were ushered into a large room where we were seated in pews.

We were told that if any of us had any guns, knives, brass knuckles, or other weapons on our person, we were to take them out and leave them on our seats. Left unspoken was the, “Or else!” part. To this day I remember the continuous clanking of metal hitting wood that seemed to go on and on. I had no idea that some of the folks I was travelling with were well armed long before they were even issued a uniform.

The eight-week training regimen had the usual components: calisthenics, learning how to march, marching, the rifle range, the grenade range, and the low crawl under chicken wire with machine gun fire above.

In a large gymnasium filled with sand pits we were given pugil sticks for mano a mano battles. I think this was to teach us that as soldiers we needed to be a little more aggressive in our approach to life.

Large signs with slogans adorned the gym’s walls. One read, “Wars were never won with conscience or compassion.” I recall thinking at the time that while that may be true, it was also true that a little more conscience or compassion might help stop wars from starting in the first place.

Approaching the end of Basic Training we were sent out into the field for a week’s long bivouac exercise.

In a final reminder that Army life was going to be different than civilian life, my training company of 120 men were marching for what seemed like forever down a gravel road surrounded by pine trees on both sides.

These woods were most unusual in that nature hadn’t made this forest. The forest was a man-made, manufactured forest. All the trees were the same 20 feet in height, and all had been planted and cultivated in perfectly lined up rows.

As we marched along the road in single file (so as not to be bunched up and more vulnerable as a group to sniper fire), I noticed two signs, one above the other, on one of the trees. The top sign read, “Hunting Area 7.”

The sign beneath it read, “No Hunting.” It was at this point that it really sunk in that my life the next three years was going to be very, very different.

Fort Holabird and Intelligence Training

One of the first things I noticed once I had stepped out of civilian life was that I had stepped into a world of acronyms I never knew existed.

After two months of Basic Combat Training (BCT) at Fort Leonard Wood, I was assigned to Fort Holabird in my mother’s hometown of Baltimore, Maryland. There I did my Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at the United States Army Intelligence School (USAINTS). At Fort Holabird, I would complete a 16-week course in my Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) and become an Army Counterintelligence Agent (97 Bravo).

At Fort Holabird, I was taught the general difference between what an intelligence agent did and what a counterintelligence agent did. I learned the job of an intelligence agent is to find out an enemy’s secrets, often through espionage. The job can also include disrupting an enemy through sabotage or psychological warfare. The job of a counterintelligence agent is to prevent an enemy from finding out your secrets, and to secure critical assets from attack or degradation. It’s a spy, counterspy, sabotage, counter-sabotage kind of thing.

All of us at the Intelligence School knew that wherever the Army might have troops stationed around the world, the bulk of our graduating class of 97 Bravos would be headed to Vietnam, Germany, or South Korea. Most others would likely be assigned to one of the U.S. Army areas in what the Army called CONUS (Continental United States). Being assigned to duty in the U.S. usually meant spending most of your Army days doing what all counterintelligence agents coming out of USAINTS were trained to do. That meant conducting background investigations of Army personnel being considered for a security clearance. Since I had been investigated this way for my enlistment into the Intelligence Branch, if I ended up assigned to do this kind of work, I feared I would have a safe, but terribly boring, circular trip in the Army.

Towards the end of my time at Intelligence School, a major assigned to the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence at the Pentagon addressed our class. His job was to describe the organization of the Army’s Intelligence Branch worldwide and the nature of available counterintelligence assignments.

When the major wound up his tour d’horizon of the Intelligence Branch realm, he closed by saying that if anyone needed to know anything further, he’d be happy to talk to him after he returned to his Pentagon office. I’m sure he thought nobody would ever actually pick up the telephone and try to take him up on his offer. However, I was so unnerved by the prospect of terminal boredom for the better part of the next three years that several days later, I called his office from a Fort Holabird pay phone. The phone was answered by a sergeant in the major’s office. I explained that I was a student soon to graduate from the Intelligence School and that I was taking up the major’s offer to personally discuss my assignment options. I was no doubt the first student that ever tried to take the major up on his offer, because the sergeant was clearly taken aback. However, he couldn’t very well tell me the major had made a mistake and now couldn’t be bothered seeing me.

The upshot was that when I hung up the phone, I thought that I had secured an appointment with the major in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence the next week. I also thought it was going to be easy getting there, as the major’s Pentagon office was relatively convenient and only an hour down the turnpike from Baltimore. However, I still needed permission from my Fort Holabird superiors to absent myself from class and leave the fort. Up the chain of command I went with my request for a temporary leave. It turned out to be one hurdle after another. There were probably four or more levels that had to clear this, and it went all the way up to the fort commander himself.

It was a struggle at each level. Normally, they all would have instinctively squashed my request just because it was unusual, and hence out of bounds. Didn’t I know there was a war on? However, every approval step ultimately caved in. I had been careful to note the Pentagon major’s promise in my request for a temporary leave of absence, so, like the sergeant, they all grudgingly acceded to the request rather than buck their own higher-ups.

Needless to say, with my fate in the immediate years ahead completely up in the air, I allowed plenty of time to drive my second-hand 1964 Volkswagen Bug down the Baltimore-Washington turnpike to the Pentagon. The last thing I wanted to do was be late for my appointment. Unfortunately, I hadn’t given thought to how and where I might park when I got there. There is no street parking at the Pentagon, which is encircled by intersecting and confusing freeways. To accommodate members of the 26,000 Pentagon workforce that drive their cars to work, the building is surrounded by massive parking lots on several of its five sides. As I quickly discovered, almost all of this parking was clearly marked as reserved for those with parking permits, and it took a long time for me to finally find that there were only two or so aisles reserved for visitors. To make things worse, there was a long queue of cars in line waiting for the occasional space there to open up. With the clock ticking and eating away at my time cushion, I got in line and began to inch forward.

It seemed like forever, but I finally got to the head of the line of cars waiting their turn to pull into the visitors’ aisle. As another car finally left, and I began turning into the aisle to park in its space, a car driving by in the opposite direction on the lot’s perimeter rudely swung in front of me and attempted to jump the line. As I rolled down my window to yell at the offender, I recognized the driver. It was my good friend from graduate school days at the University of Chicago, Jan Grayson.

My anger quickly dissipated as we both pondered the oddness of our meeting. He told me he was in the Army Reserves in a biological warfare unit that had a meeting at the Pentagon. Under the circumstances, I decided to forgive him when I understood he knew even less than I did about the parking challenges at the Pentagon. I took him at his word when he promised to never cut me off in the visitors’ parking lot again. Further proof of my charitable nature came when I asked him years later to be my son Pat’s godfather.

When I finally got inside the Pentagon for my meeting, the sergeant said something had come up, and the major was tied up. He told me he would be meeting with me in his stead. My argument to the sergeant was simple. I told him I was older than almost all of the Intelligence School trainees and had college, law school, and a year of private law practice under my belt. I said it might benefit both me and the Army if there was an assignment for me that could make use of this specialized training. He pulled my class roster tacked to a bulletin board behind him and found my name on the list. Then he gave me the bad news.

He said all the assignments were pretty much computer-driven, and there was really no way my ultimate assignment could be predicted at that point. He politely thanked me for driving down to chat and told me to drive safely on my return to Fort Holabird.

While I was disappointed that I had been left still swimming in a sea of uncertainty, I did have the satisfaction of having at least taken a shot at influencing the nature of my next two and a half years in the Army.

Assignment to the 902nd Military Intelligence Group

Before long, assignment day arrived. Next to my name on the class roster was “902nd MI Group.” All I could find out about the 902nd was that it was an organization attached to the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence of the Army and was located at Bailey’s Crossroads in Virginia, just west of the Pentagon.

I found out it was also a stabilized tour. I then knew I would be working in the Washington, D.C., area until I left the Army and that I would wear civilian clothes to work each day. Being in mufti instead of a uniform was an unexpected perk.

Not long before graduation at USAINTS, I drove down to Bailey’s Crossroads to where I was told the 902nd offices were. All I could find there was a small L-shaped suburban strip mall at a crossroads. I was certain I’d been given bum instructions either accidentally or on purpose as a ruse.

After graduation, I got a better address for the 902nd Headquarters where I was to report. Strangely, it was the same L-shaped strip mall I’d been directed to earlier.

This time I noticed there was a second story to the building on the mall’s west side with unusual antennas on the roof.

I also noticed that there was one nondescript entrance on the lower level with a glass door, but no store behind it. Instead, there was a narrow staircase leading up to who knows what on the odd second story. I passed multiple surveillance cameras as I climbed the stairs.

At the top, I found a Mr. Parkinson. He was a Department of the Army civilian, and the administrative chief of the office. I was welcomed and told I would be technically attached to nearby Fort Meyer, assigned to the Counterintelligence Analysis Division of the 902nd, have an office elsewhere, and could rent an apartment with two other 902nd enlisted men anywhere we chose within commuting distance.

This was my introduction to the world of Army spooks.

CIAD in the CD of OACSI at DA in DC

In November 1968, the Counterintelligence Analysis Detachment (CIAD) of the Counterintelligence Division (CD) of the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence (OACSI) of the Department of the Army (DA) in the District of Columbia (DC) was located in an obscure warehouse building off the beaten path of Bailey’s Crossroads. The adjacent space was taken up by a Northern Virginia Community College automotive repair training workshop. A traditional mission of the 902nd MI Group, of which CIAD was a part, was maintaining security at the Pentagon. This had taken on greater importance following the October 21, 1967, antiwar march on the Pentagon. The march of 20,000 to 35,000 demonstrators had followed the 100,000 strong rally on the Mall by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. This large demonstration against the Vietnam War was immediately chronicled when Harper’s Magazine published Norman Mailer’s 25,000-word article, “The Steps of the Pentagon,” in March 1968. This piece later appeared as the epilogue to Mailer’s Pulitzer Prize-winning antiwar book of New Journalism, The Armies of the Night.

Apart from physical security issues, since the Pentagon was the center of the nation’s military establishment, the building always housed a motherload of military secrets the Soviet Union and other bad actors of the day were always targeting. As a result, part of the 902nd was colloquially referred to as “the night crawlers.”

This group was largely made up of enlisted men who spent their nights patrolling the Pentagon corridors and offices looking for security violations such as filing cabinets left unlocked. This was the kind of boring drudgery I mostly escaped at CIAD. However, I did get assigned once to one of these night crawler details. As soon as the day workers at the Pentagon departed, I began the rounds of a section of deserted offices looking for filing cabinets left unlocked and collecting the large striped paper trash bags filled with all the classified documents people had thrown out during the day. That was the night I learned the way to the Pentagon’s municipal-grade furnace for daily classified document disposal.

The Counterintelligence Analysis Detachment, as the name suggests, didn’t directly run any spies. It was instead in the business of digesting the production of pertinent intelligence gathered primarily by other Army and service intelligence units, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, among others. The goal was to sift through this production and cull out what pertained directly to performing the Army’s designated counterintelligence missions.

A number of CIAD analysts were assigned to read and evaluate counterintelligence reports from Vietnam. During my time there, a young analyst with this job had the time to put two and two together in a way that wasn’t possible for his time-pressed counterparts in Saigon. Though the details of his breakthrough were as usual kept under “need to know” wraps, the CIAD chief organized a small party to celebrate and honor my colleague. Thanks to his careful analysis of the counterintelligence traffic crossing his desk, he had pretty much single-handedly caused a North Vietnamese spy ring in Saigon to be rolled up.

When I began my day-to-day work at the Pentagon, my lowly rank as an enlisted man was disguised by my civilian dress. The point of this was to let me freely interact with the many uniformed senior officers I was working with by eliminating rank from the interaction. Being in my mid-20s at this point, these soldiers were not only all senior to me in age. As I also quickly learned, their Pentagon slots were frequently either pre-retirement, capstone assignments at the end of 20 years of service or waystations to major command responsibilities elsewhere in the Army’s global footprint.

A further element that distinguished these senior officers from me was the fact that many had just rotated into the Pentagon from wartime combat assignments in Vietnam or other Cold War hotspots. At one time or another, many of these men had come from leadership roles that had directly exposed them to the random death and destruction inherent in wartime combat, the very combat that I had intentionally tried to steer my military career away from.

One of these men that I became particularly close to was a Lieutenant Colonel his late 40s at the end his Army career. He had grown up in a working-class Boston family, and his Boston accent had not diminished during his nearly two decades in service. I was aware he had recently returned from leading combat troops in Vietnam. Being curious, when I had an opportune moment with him one day, I asked him what struck him most about his own particular wartime service. While he had at least one Vietnam tour of duty behind him, and maybe two, he spoke to me of only a single incident.

He said at one point he was in command of soldiers looking for members of another unit that had recently gone missing after a battle. He described how they made their way through thick vegetation until they came to a clearing with a devastating scene. “There they were --- the men we were looking for. They couldn’t be rescued at that point, because they were all dead. As we got closer to their corpses, I could figure out what happened. They had been captured by the Viet Cong but hadn’t been kept long as prisoners. They’d been lined up and shot with a bullet to the back of their heads.”

“What did you do?” I asked. “Obviously, I directed my guys to begin to gather the remains, so we could bring them all back.” As he went on, he spoke more slowly and began to weep, “My guys were mostly just kids 18 or 19, and here they were looking at this absolutely horrific scene. But they knew they had a job to do, and they went about that job methodically, like adults, but stone-faced. I was so proud of them. And they were only 18 and 19-year-old kids doing this kind of thing!” When he stopped talking, he was crying. Thinking about him reminds me that it isn’t only the dead who pay a price in wartime. Those that may be ineligible for a Purple Heart can bear a painful psychic scar. Often, one that can last a lifetime.

Some parts of the 902nd’s duties, like Pentagon security, never changed much. But race riots, which had racked the country in 1919 and 1943, were recently back on the Army’s agenda. In the summer of 1967, right before the march on the Pentagon, the Regular Army had been called into Detroit by the Michigan Governor and the President to help quell its violence.

After the Detroit riot and the march on the Pentagon, the recent takeaway for the Army was that it needed to be much better prepared for a continuing period of civil and racial unrest.

The Vance Report

Following the Detroit riot, former Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance (then serving as Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense Concerning the Detroit Riots) prepared a study to reassess the Army’s preparedness for this new role.

The Vance Report had concluded that the use of the Army to help control antiwar demonstrations and racial disturbances wasn’t an isolated, one-off mission, and the requirement wasn’t going away any time soon.

An abstract of the Report’s lessons learned reads:

Based on the experiences in Detroit, where rioting and lawlessness were intense, it appears that rumors are rampant and tend to grow as exhaustion sets in at the time of rioting. Thus, authoritative sources of information must be identified quickly and maintained. Regular formal contact with the press should be augmented by frequent background briefings for community leaders. To be able to make sound decisions, particularly in the initial phases of riots, a method of identifying the volume of riot-connected activity, the trends in such activity, the critical areas, and the deviations from normal patterns must be established. Because the Detroit disorders developed a typical pattern (violence rising then falling off), it is important to assemble and analyze data with respect to activity patterns. Fatigue factors need more analysis, and the qualifications and performance of all Army and Air National Guard should be reviewed to ensure that officers are qualified (National Guard troops in Detroit were below par in appearance, behavior, and discipline, at least initially). The guard should recruit more blacks (most of the Detroit rioters were black), and cooperation among the military, the police, and firefighting personnel needs to be enhanced. Instructions regarding rules of engagement and degree of force during civil disturbances require clarification and change to provide more latitude and flexibility. Illumination must be provided for all areas in which rioting is occurring, and the use of tear gas should be considered. Coordination at the Federal level to handle riots is emphasized. Appendixes include a chronology of major riots, memos, a Detroit police incident summary, police maps of Detroit, and related material.

Secretary Vance’s report came out in early 1968, just before race riots had exploded in Black neighborhoods of 130 cities after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4. Many states called up their National Guard troops to join police in bringing the rioting and looting under control. Simultaneously Regular Army troops had to be flown or trucked into Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Chicago from various Army bases. In all cases, they had to back up overwhelmed police and National Guard security forces. In the middle of the Vietnam War, this was not a mission for which the Army was either structured or prepared for. Two months later, the sense of mayhem in the country increased further when Presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles.

I was familiar with this new problem for the Army, since right before I enlisted, I had watched Chicago’s west side erupt in flames from my Loop office window, and later directly witnessed some of the rioting firsthand with my brother, Dick, who worked for the City’s Human Relations Commission. I also monitored bail and other court proceedings involving rioters at the Criminal Courts building at 26th Street and California Avenue.

In this period, Regular Army troops were bivouacked near the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago’s Jackson Park. The next month I was in the Army, and six months after that, I was again engaged with civil disturbances.

During the summer of 1968, Chicago remained in turmoil. Though Regular Army troops had left and returned to their barracks, violent anti-war demonstrations continued to wreak havoc on the city. Rampaging groups of demonstrators before the Democratic National Convention that August brought out the Chicago police in full force as well as the Illinois National Guard.

My brother Dick remained in the middle of this activity. His Report to the Director of the Chicago Human Relations Commission provided a detailed account of the anti-war demonstrations and violence he witnessed between August 24 and 28, 1968. The Report gives a street-level view of the disturbances in both Lincoln and Grant Parks. The final confrontation between the demonstrators and police and National Guard in front of the Hilton Hotel took place during the Democratic Convention’s proceedings and provided a violent backdrop to its nomination of Hubert Humphrey to run against President Richard Nixon that fall.

In 1964, there had been race-related riots in Harlem and Philadelphia. In 1965, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles had seen a major race-related riot. Chicago, Cleveland, and San Francisco saw riots the next year. Then in 1967’s “Long Hot Summer,” a total of 163 cities were enflamed, including Atlanta, Boston, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Detroit, Milwaukee, Newark, New York, and Portland. Following Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, President Johnson dispatched Regular Army troops to Baltimore, Washington, and Chicago to supplement overwhelmed police and National Guard.

In the aftermath of these troop deployments, President Johnson created the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence.

With the nationally televised violence directly in the political realm later that year at the Democratic Convention, the Commission had delegated to Daniel Walker, later Illinois governor, the job of undertaking a study of the violence surrounding the Convention.

The Walker Report was formally titled Rights in Conflict: The Violent Confrontation of Demonstrators and Police in the Parks and Streets of Chicago During the Week of the Democratic National Convention of 1968.

It found there had been a “police riot” in addition to violence on the part of more than 10,000 anti-war demonstrators.

In The Walker Report, you will find a picture taken by a Time Magazine photographer of my brother, Dick, about to remove a burning trash basket blocking traffic in the middle of La Salle Drive at the south end of Lincoln Park.

If not for Dick’s ever-present pipe sticking out of his mouth, I might not have recognized him or taken him to be one of the demonstrators, rather than an observer from Chicago’s Commission on Human Relations.

Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations

One of Vance’s recommendations after Regular Army troops had been sent to quell the extreme violence in Detroit in 1967 was to create a joint service command unit to oversee the mission of controlling civil disturbances when the Army was called to deploy troops by a Governor and the President. Thus, was born the Department of Defense’s Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations. DCDPO had an Army Lieutenant General in command, with an Air Force Major General as his Deputy.

Immediately prior to my arriving at CIAD, the then-classified Department of the Army Civil Disturbance Plan (Code Name: Garden Plot) was published on September 10, 1968. In a strange coincidence that arose later, Garden Plot’s author and the first head of DCDPO I worked for was Gen. George R. Mather. After my brother Dick’s divorce, Mather’s son later became my niece and nephew’s stepfather. The good General went on to retire from the Army at the same time I did. However, while I left as a Sergeant, he wrapped up his distinguished Army career with four stars after leaving DCDPO to serve as head of the Army’s Southern Command.

When I began my work at CIAD in November 1968, I was given the task of reviewing domestic intelligence relating to the likelihood of DCDPO being asked to again deploy troops to American cities. With this background in mind, I was assigned to provide intelligence needed by DCDPO for both planning and operational purposes. My reading diet for this task included classified government documents which were primarily and voluminously produced by the FBI, and to a lesser extent the Army. I found open-source, non-classified material was usually of more utility than the classified sources in making judgements about whether and when Regular Army troops needed to be alerted for possible deployment.

By the mid-1970s I was back in civilian life, and the country had become considerably calmer. I imagine DCDPO withered away with the changing times, and a half-century would have to pass before the country again saw the widespread civil unrest of the early 2020s.

Bernardine Dohrn and the Rise of the SDS Revolutionaries

In summer 1968, I had been going through the Army’s Intelligence School at Fort Holabird, and that fall I had been getting my arms around providing intelligence assessments to the Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations on the likelihood of Regular Army deployments to assist in controlling racial unrest. In this short period of time, another major factor began to enter into my professional purview besides the continuing deterioration of race relations in the country. This new factor had a lot to do with what one of my University of Chicago Law School classmates had been up to in her year since graduation.

Bernardine Dohrn had earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and had been one of the small number of women who entered the University’s law school with me in fall 1964. Our law school class had 150 incoming students. While most of the first-year students wore trousers, Bernardine stood out with both her miniskirts and her politics.

The summer after our second year in law school, my brother Dick was working for the City’s Commission on Human Relations. A large rent strike with racial overtones was underway at the former Marshall Field apartment complex in the city’s Old Town neighborhood. I was interested in landlord/tenant law reform at the time, so I took my brother up on his invitation to join him in looking at what was going on. At the site, I found my classmate Bernardine by the picket line. While I was there out of a largely academic interest, Bernardine explained she was there to directly assist the cause of the rent strikers and show her solidarity with the tenants.

The only other law school contact with Bernardine I recall was when I pulled a group of classmates together to help prepare a traditional third-year spring skit. The goal of the exercise was always to relieve some of the tensions of upcoming final exams by poking fun at student obsessions of the day and making sport of notable faculty. I’m not sure why Bernardine turned up, because she found absolutely no humor in any of the subjects put on the table for discussion and took no further part in the effort. While I was in no position to conclude from this that Bernardine was humorless, looking back on much of the language Bernardine later came to use, it occurred to me that it might be difficult to find anything to laugh about if you’re a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary committed to using violence to overthrow the U.S. Government because it’s a racist, imperialist, capitalist, misogynist, and xenophobic regime with its white supremacist jackboot on the oppressed necks of the under trodden.

Following graduation from law school in 1967, Bernardine took a job organizing law students for the left-wing National Lawyers Guild and became active in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In June 1968, just as I entered Intelligence School, she became the Inter-organizational Secretary of SDS, and just three months later, SDS played a role in the violence that broke out in Chicago during September’s Democratic National Convention. The ensuing battles of anti-war demonstrators with police and National Guard in the Convention’s run-up drew a worldwide television audience.

In December 1968, Bernardine helped lead a celebration in New York City of The Guardian newspaper’s 20th anniversary. The Guardian had a Maoist bent and was then a prominent weekly organ of the New Left. Her co-host at the gathering was Herbert Marcuse, a leading academic philosopher of revolutionary upheaval then teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In her remarks, Bernardine denominated Marcuse as “the ideological leader of the New Left.” Marcuse in his own remarks went on to envision the New Left’s coming “political guerrilla force.”

In this increasingly roiled political atmosphere, large scale anti-war demonstrations and anti-government violence in the form of bombings and arson events began to loom large as I prepared my estimates on the likelihood of the President having to deploy Regular Army troops in a civil disturbance control mission. Indeed, in one 18-month period in 1971-72 alone, over 2,500 domestic bombings were cataloged. This new development of broad-scale political unrest joined the extant racial violence as possible contributors that might call for Regular Army troops to supplement police and National Guard forces in a domestic peacekeeping role.

In June 1969, Bernardine Dohrn led a split in the SDS at its national convention in Chicago and, in an accompanying manifesto, Bernardine and her Third World Marxists group in SDS advocated street fighting as a method for weakening U.S. imperialism. The Third World Marxists presented a position paper titled “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows” in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes. The position paper title was taken from a song by Bob Dylan and argued that Black liberation was central to the movement’s anti-imperialist struggle. It explained the need for a white revolutionary movement to support liberation movements internationally. The manifesto became the founding statement of the SDS Weatherman faction. The Weather Underground, as the hard-core group soon called itself, quickly became responsible for what it called the Days of Rage violence in Chicago in October 1969. The premise for this mayhem was the commencement of a criminal trial of the Chicago Seven, leaders of the Chicago Convention violence the prior year. Not long after this, the Weather Underground followed with bombings of the United States Capitol, the Pentagon, and several police stations in New York, as well as a Greenwich Village townhouse explosion in New York City that killed three Weather Underground members. Along the way, Bernardine was quoted as announcing, "I consider myself a revolutionary communist."

With these events unfolding, Bernardine appeared as a principal signatory of the Weather Underground's “Declaration of a State of War” in 1970. This document formally declared “war” on the U.S. Government. Having confirmed the group’s dedication to revolutionary violence, Bernardine went on to record the declaration and send a transcript of it to The New York Times. In my role providing intelligence support to DCDPO, among other open and classified materials, I read a steady flow of Federal Bureau of Investigation reports on internal security matters. For decades the FBI had focused its counterespionage and countersubversion resources on the Communist Party of the United States.

By the late 1960s, however, CPUSA, as the acronym had it, had faded in the priority list of targets. It had been displaced in importance by what was termed by the FBI as the New Left. So it was that a little over a year following my law school graduation, fat FBI dossiers on my classmate Bernardine Dohrn and her later husband, Bill Ayers, landed on my desk in the new Army Operations Center. These reports on Dohrn and Ayres were typical background compilations. As the pair’s bent towards violence increased, so did the FBI’s surveillance activities. In a major embarrassment for the FBI, the government’s misconduct and overreaching in this regard resulted in them escaping punishment for the serious criminal charges they faced.

The Army Operations Center (AOC)

The 1967 emergency deployment to Detroit had caught the Army by surprise, and Secretary Vance had also recommended that a new war room in the Pentagon be built to coordinate up to 25 simultaneous deployments of Regular Army troops to American cities. And so was built the new Army Operations Center (AOC).

I remember being on duty in the new AOC in January 1969 when President Richard Nixon was being sworn in. With the country on edge in the aftermath of the riotous Democratic Party convention in Chicago the preceding fall, the seat of the federal government was a constant target for antiwar demonstrators, and the frequency and size of their gatherings in Washington were increasing. The AOC was in a subbasement Pentagon space. Built as a duplex war room with ancillary offices, its entrance was guarded day and night and restricted to those with proper security clearances. On one side of the two-story war room atrium was a glassed-in command balcony where civilian and military decision makers sat. From this perch they could look down upon the military worker bees at their desks on the floor below, or they could look straight across the atrium at the wall opposite.

This wall was filled with several large projection screens showing maps and troop positions. Other screens could display any live television coverage of ongoing demonstrations.

In standard military fashion, operational briefings in the AOC began with a uniformed Air Force officer giving the weather report. Addressed always as Mr. Bowe, with no indication of rank, I would follow in civilian dress with the intelligence report. As you might expect, the most useful intelligence had to do with the expected size and likely activity of demonstrators. For this purpose, widely available, non-classified newspapers and other common publications were a primary source I used to build my estimates.

The Air Force weather officer and I would precede the operations portion of an AOC briefing. All speakers would deliver their remarks from glass briefing booths on either end of the upper level of the AOC. The briefers were visible to the adjacent command balcony, and, because the pulpit-like booths jutted out a bit over the lower level, briefers were also visible to the joint service officers coordinating information on the lower level. The only thing I had seen like this was the isolation booth Charles Van Doren was in when he answered questions on the rigged Twenty-One television quiz show in the late 1950s, and the bulletproof glass cage where Nazi Adolf Eichmann stood when he was on trial for war crimes in Israel in 1961. While the AOC was a state-of-the-art war room for 1968, later decades made it in retrospect look like a modest starter home compared with the McMansion war rooms that became all the rage.

I always thought Van Doren and I did better than Eichmann after we left our respective glass booths. Eichmann, of course, got the noose, but both Van Doren and I later in life worked on a Greek-language publishing project that Van Doren had initiated at Encyclopaedia Britannica. This was shortly before he retired and I arrived. Years later, when Van Doren came to Chicago in 2001 for his mentor Mortimer Adler’s funeral, I mentioned to him that I had inherited this last project of his.

The AOC could be a strange place at times. In December 1968, I saw accused mass murderer Lieutenant William “Rusty” Calley, Jr. in the AOC. I had my desk at the time in the AOC, and one day after lunch, as I came in past the security desk at the entrance and entered the complex, I happened to glance to my left into the anteroom. There, looking very much alone, sitting by himself at a small table, was Calley. I recognized him immediately. His time in Vietnam had landed him on the cover of both Time and Newsweek that week. With the tragic My Lai Massacre all over the press, he had been sequestered for interrogation by the Army in the safest out-of-the-way spot it could find for him, the AOC.

Sometime in 1969, before I got my office in the AOC, CIAD had moved from our windowless quarters next to the Northern Virginia Community College’s automobile shop to more upscale quarters in the Hoffman Building office complex in Alexandria, Virginia. This building had plenty of light, was near the beltway, and was close to the Wilson Bridge over the Potomac. While I had a desk there for the duration, I was spending most of my time in either the AOC or another Pentagon office.

Another space at the Pentagon that I rotated through daily was entered through a nondescript door on a busy corridor on one of the Pentagon’s outer rings. I was moving up in the world. Having started with an interview in OACSI’s lowly assignment office, I had moved up to a first-class basement duplex with the AOC. Now I had been promoted part of the day to an above-ground cubby hole in one of the prestigious outer rings.

In this easily overlooked spot in a highly trafficked hall, one indistinctive door led to a small reception area. I regularly had on a neck chain my Army dog tags, my Pentagon ID, my Hoffman Building ID, my AOC ID, and an ID for this area. Behind the door’s guard was an inner sanctum of windowless offices. This space was where highly compartmentalized, secret intelligence information collected by various foreign and domestic intelligence agencies could be viewed. It was interesting stuff to plough through daily, but rarely bore directly on my main job of preparing and delivering written and oral briefings on the likelihood of demonstrations or civil disturbances.

The Blue U and CIA Training

In June 1969, just as I turned 27, I was selected to join a dozen other Army counterintelligence agents at a special school conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency’s Office of Training. The focus of the two-week course was a survey of worldwide communist party doctrine and organization. Being designed for counterintelligence agents, the survey explored both open and underground tactics used to expand communist power and influence. I had been a political science major in college, concentrating on international relations in the 20th century, so some of the curriculum was more entry level than not from my point of view. The most interesting of the topics covered for me was the examination of Soviet and Chinese intelligence agency organizations and tactics.

As was true for the Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System Security Group I later joined, this activity took place in an Arlington, Virginia, office building. Now long gone, the building then was known colloquially as The Blue U for its unusual color and shape. I found that my first day of school at The Blue U was a lot like my first day trying to find the 902nd MI Group headquarters. I had general directions to get there, but no idea of what I’d find when I actually set foot in the place. The CIA training activity was under what was called “light cover” inside the Blue U. It seemed from the lobby directory that the building housed a variety of routine, non-intelligence Defense Department activities. There were Army and other service functions listed in the lobby directory, but nowhere did I see the CIA school listed. That’s because it was operating under an innocuous and forgettable pseudonym like “Joint Military Planning Office.” I got in the elevator with a handful of others dressed in both uniforms and civilian clothes and pushed the button for my floor. At each floor the elevator stopped, and people got off as normal. However, when we got to my floor, those left on the elevator with me immediately pulled out previously hidden identification cards. The result was that when the elevator door opened on the top floor, and an armed guard immediately confronted us, everyone else already had an ID out. They were the regulars, and I was obviously the newbie.

The office had lots of closed doors on both sides of narrow corridors. None of the doors had names or any indication of what functions lay within, so it was more than a little spooky.

It turns out another member of my extended family also spent time in The Blue U. Years later, I was visiting my cousin John Bowe and his wife, Kathie, at their summer home in Cape Porpoise, Maine. Kathie Bowe’s brother Allan joined us for dinner one evening, and before long we found out we had both done time at The Blue U. While I was a student employed by the Army, he had been a teacher there employed by you know who.

The Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System

Though large antiwar demonstrations and racial disturbances were a common part of the American scene when I was in the Army between 1968 and 1971, they weren’t demanding all my time by any means.

One project that I devoted a lot of time to in 1969 was a counterintelligence study related to the Army’s Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) System under development. I was appointed to a working group in downtown Arlington, Virginia, tasked with understanding the counterintelligence issues associated with the Army’s new Safeguard ABM system. Safeguard was a successor to earlier Nike missile systems.

Nike had been designed to intercept Soviet nuclear bombers. Safeguard was to defend against intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

My contribution to the group’s work was to make a detailed analysis of the possible espionage and sabotage threats to the Safeguard system’s functionality.

Huntsville, Alabama, and the Army Missile Command

As I thought about what it would take to do the counterintelligence study correctly, it quickly became apparent that I needed to get out of the Pentagon and talk firsthand to the people who were or would be designing, building, testing, and operating the Army’s new high-tech weapons system then under development.

This meant I had to travel first to the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, at the time the headquarters of the Army Missile Command. Next, I needed to go to the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) in Cheyenne Mountain, near Colorado Springs, Colorado. The NORAD part of the trip was key for me to understand how the system was designed to operate in wartime conditions. Finally, I needed to travel to Kwajalein Atoll.

What was then known as the western terminus of the U.S. Pacific Missile Test Range is today called The Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Test Site. In 1969, the Safeguard ABM system’s radars and Sprint and Spartan missiles were being tested there.

As expected, I learned a great deal at my first stop at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville.

NORAD and Cheyenne Mountain

My following visit to Cheyenne Mountain and NORAD’s Headquarters wasn’t just interesting and useful. It turned out to be absolutely fascinating as well. NORAD was a joint U.S.-Canadian command that had begun in the 1950s with its backbone being the Distant Early Warning (DEW) line of radars across the Canadian tundra. By 1969, when I received my NORAD Mission Briefing, it was already tracking space junk, and reorienting its mission from defending against the earlier era’s nuclear-armed Soviet bombers to defending against Soviet nuclear-tipped ICBMs. Today, NORAD describes its missions this way:

Aerospace warning, aerospace control and maritime warning for North America. Aerospace warning includes the detection, validation, and warning of attack against North America whether by aircraft, missiles, or space vehicles, through mutual support arrangements with other commands.

You entered the NORAD complex by being driven deep into a tunnel under all-granite Cheyenne Mountain, just outside of Colorado Springs, Colorado. Getting out of the vehicle, you had to pass through two enormous blast doors. They were designed to keep those inside the doors safe from the radiation and blast effects brought about by nuclear warheads hitting the mountain. Through the blast doors, a short tunnel took you into an enormous cave-like chamber. In it were multi-story prefabricated offices rising to the cave ceiling many stories above. These office structures sat on large I-beams on the cave floor. All the communication, water, and power utilities fed into the office structures through giant spring connections on the I-beams. The whole design was to permit the structures to ride out a nuclear attack on the mountain complex without its functionality being knocked out.

In James Bond parlance, this was to make sure that, in the event of a nuclear attack on NORAD’s mountain headquarters, those working within would be stirred, but not shaken. My early education here regarding space-related defenses was a preview of what we would all come to see in later years. Today, space is doctrinally and organizationally recognized as its own theater of war. But official recognition of this evolution didn’t occur until recently, a full 50 years after my visit to Cheyenne Mountain. It was only in 2019 that the President and Congress shifted the mission of ballistic missile and satellite defense to our newly created U.S. Space Force.

Johnston Atoll and the Origins of Space Warfare

I knew Kwajalein was going to be a very different place, but I didn’t understand that getting there would turn out to be a surprise, too.

Northwest Airlines, with its distinctive fleet of red-tailed passenger jets, had a contract with the government to fly military personnel and civilian contractors with security clearances from Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu, Hawaii, west to Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. I knew how long the non-stop flight to Kwajalein was going to take, so I was surprised when we suddenly began descending well short of our destination. There was no engine malfunction, so why land in the middle of the Pacific if you didn’t have to? I had no desire to emulate Amelia Earhart, so I was increasingly nervous about what might be an unexpected descent into oblivion.

My anxiety was quickly relieved when the pilot came on the squawk box to say we should buckle up for landing to refuel at Johnston Atoll. The runway at Johnston seemed only about as long as the atoll itself, leaving no room for error on the pilot’s part. I stared out the airplane window in awe as we decelerated, finally rolled to a stop, and then taxied back to the other end of the runway to deplane.

Though my visit was short, Johnston Atoll ended up being one of the strangest places I have ever been to in my life. It’s a small, isolated, and currently uninhabited atoll in the vastness of the south-central Pacific, and it lacks natural access to any fresh water. Despite these impediments to human habitation, I later learned that Johnston Atoll had a long, if fitful, history of human habitation before my arrival in late August 1969. Indeed, there was a period when over 1,000 personnel, some accompanied by their families, lived on Johnston Atoll. These folks were working on extremely dangerous military projects in the highest level of secrecy.

Johnston’s history started late. In 1796, the Boston-based brig "Sally" first discovered the atoll when it ran aground there while transiting the Pacific. The British ship HMS Cornwallis bumped into Johnston a few years later in 1807. Its Captain, one Charles Johnston, quickly and immodestly named the atoll after himself. Commercial development of the Atoll's substantial guano deposits began after the U.S. Congress authorized this business in the mid-19th century. In the 20th Century, when the guano enterprise was long gone, the U.S ships Tanager and Whippoorwill did scientific surveys in the 1920s.

During World War II, Johnston served as a Navy and Army Air Force refueling depot. Then, during the Cold War, military requirements changed. This led to substantial dredging of the Atoll’s coral reef and shallows and the incremental expansion of the tiny Atoll’s land.

Beginning in the late 1950s, U.S. defense planners began to become worried that the Soviets might soon be able to launch satellites into orbit with nuclear bombs aboard that could be launched at will on ICBM installations in the US or, God forbid, on U.S. cities. This worry raised the concomitant question as to whether such orbiting satellites could be destroyed by detonating a nuclear warhead in their vicinity. To test this theory, in 1958 the first of a series of lower altitude nuclear tests began at Johnston Atoll. The purpose of the Project Fishbowl test in 1962 was to find out what happens when you detonate a nuclear weapon in the upper atmosphere.

In the anti-satellite tests at Johnston, modified Thor missiles with nuclear warheads atop were launched to see whether X-rays generated by detonation of their warheads would actually be capable of destroying hostile Soviet satellites. In one early test failure, a Thor missile blew up on its launch pad and spewed plutonium over the Atoll. This resulted in a complicated and lengthy cleanup effort.

However, these early test failures were nothing compared with the spectacular 1962 nuclear explosion that was set off in the upper atmosphere 248 miles above Johnston. The first thing this early morning nuclear blast produced was a startling artificial sunrise, an Aurora Borealis that lasted for minutes and could be seen all the way from New Zealand to Hawaii. Of more consequence, no one had foreseen the startling and damaging effects of the electromagnetic pulse generated by the explosion of a nuclear device on the edge of space. On the benign side was the EMP effect that resulted in the inadvertent opening of automatic garage doors in faraway Honolulu. However, a more serious consequence of EMP effects was that the test showed a single detonation above some countries could knock out their entire electrical grid.

Also not foreseen was the negative impact of this detonation on the Van Allen Belt that protects the earth from solar storms, and the damage that could be caused to useful low orbit earth satellites. Among these victims, Telstar, mankind’s first telecommunications satellite, was rendered dysfunctional by the blast. The next year following this unintended result, right after the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1963, the Limited Test Ban Treaty was signed by President John F. Kennedy. It forbids nuclear tests in the atmosphere, underwater, and in space.

I had never heard of Johnston Atoll and knew none of this history while en route to Kwajalein Atoll in 1969.

As a result, as we were landing at Johnston, my jaw dropped as I noticed that on either side of the runway were rows of large Quonset-like sheds. They seemed to be connected by train tracks and outside one of the sheds was a large horizontal missile being worked on by two uniformed men.

I was befuddled. What was I looking at here in the middle of nowhere? There seemed to be no rational explanation for what I saw. None of my many classified briefings on our missile and anti-missile developments up to that point had even hinted at the existence of such an unusual installation. It was not until many years later that the history of this secret installation was declassified, and I learned that these all these sheds contained Thor missiles that were part of Project 437, a functional and operating anti-satellite weapon system authorized by President Johnson and fully capable of destroying Soviet satellites that might be carrying nuclear bombs. Oddly, almost at the same time as I landed at Johnston, the Air Force made the decision to shut down its anti-satellite installation.

From a counterintelligence planning standpoint, with defense troops far away in Honolulu, there had always been some concern about Johnston’s vulnerability to attack from a submarine or a commando assault in a run up to a real-world nuclear exchange. However, Johnston’s anti-satellite mission turned out to be more a victim of technological obsolescence and the increased budget constraints brought about by the still growing Vietnam War expenditures.

After we deplaned to refuel at Johnston, we had been ushered past a no-nonsense MP with his weapon drawn into a small, single-story, air-conditioned space. As we sat on plain benches waiting for the refueling to finish, it was hard not to notice the storage cubby holes on each wall and the multiple black hoses hanging down from the odd piping strung from the ceiling. Nothing was said by anyone about all this and in short order we reboarded our airplane and proceeded to Kwajalein uneventfully.

As was true with my delayed knowledge of the Thor anti-satellite weapons system, it was years later that I learned that Johnston Atoll’s unique position in the Pacific Ocean made it a useful place for CIA SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft to refuel on their missions over Vietnam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and ‘70s. The Blackbirds could travel over 2,000 miles per hour and held an altitude record for flying over 85,000 feet. Their high-altitude flights required early versions of the space suits and helmets the astronauts later wore. Hence, the cubby hole storage cabinets. The ceiling pipes and related hoses were also a necessity in the Johnston ready room. They were there to feed the SR-71 pilots’ oxygen in the acclimating runup to their departure.

In the most recent chapter in Johnston Atoll’s history, in the 1990s Johnston was again reengaged to deal with a major national security threat. Vast stocks of aging chemical weapons secreted around the world were beginning to leak and were in danger of becoming unstable enough to explode. Johnston's new mission became the destruction of the deadliest non-nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. It took over a decade, but an enormous furnace was built on Johnston that safely incinerated these stocks before they created an unintended disaster. At the peak of this effort, over 1,200 military and contractor personnel lived and worked on Johnston. Then, when the toxic stores were gone, all the housing and all of the other infrastructure on Johnston Atoll was destroyed and its runway shut down. Johnston wasn't just decommissioned in 2004, it’s fair to say it was “terminated with extreme prejudice.”

So today, Johnston Atoll has reverted to its long uninhabited state and has little wildlife other than the fish that inhabit its coral reef. Knowing something today of Johnston’s history, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the fish glowed in the dark.

As our Red Tail jet took off from Johnston for Kwajalein, the then unanswered mysteries of Johnston Atoll went with me. I had a heightened curiosity as to what I’d find at my next stop. Kwajalein was an even bigger and more important outpost for the cutting-edge military technology being built at the time for the developing war theater of space.

Kwajalein Atoll—The Ronald Reagan Missile Test Site

Kwajalein Atoll was then the western terminus of the Pacific Missile Test Range. Then and now, Kwajalein functions as a critical facility that tests the accuracy of U.S. ICBM missiles and their Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicle (MIRV) nuclear warheads. For more than half a century it has also been testing the efficacy of anti-ballistic missile missiles designed to track, intercept, and vaporize hostile, incoming ICBM nuclear warheads. That so-called exercise of “hitting a bullet with a bullet” was hard to do more than a half-century ago, and it hasn’t gotten any easier since with the recent Chinese and Russian development of hypersonic missiles.

Our plane landed on Kwajalein Island, the largest and southernmost island in the Kwajalein Atoll. Kwajalein is due north of New Zealand in the south Pacific and due east of the southern part of the Philippines. In short, like Johnston Atoll, it’s in the middle of nowhere. The Atoll is made up of about 100 islands in a coral chain 50 miles in length, stretching from Kwajalein Island in the south to Roi-Namur Island in the north. Kwajalein Island is only three quarters of a mile wide and three and a half miles long. The whole of the Atoll’s coral land is only 5.6 miles square. The Atoll is about 80 miles wide, which makes it one of the largest lagoons in the world.

The people I most needed to talk to on Kwajalein were the senior Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientists and Raytheon engineers most familiar with the Safeguard missile development (both the short-range Sprint Missile and the exo-atmospheric Spartan Missile). I also needed to learn more about the functioning of the Phased Array Radar (PAR) central to Safeguard’s ability to track and intercept incoming warheads before vaporizing them with X-rays from a nuclear detonation.

My interviews on Kwajalein Island and Roi-Namur were delayed due to my being bumped by a Congressional staff visit that happened to conflict with mine. Recent glitches in the Safeguard testing had apparently triggered a closer Congressional look at the state of the program and its related budgeting problems.

To have something to do in the meantime, my Army host, who also served as the base recreation officer, took me out to golf. What a course! It lay on either side of Kwajalein Island’s single runway. The narrow greensward where you could play was studded with radars used in the Island’s missile testing work. The so-called fairways had a picket fence on their ocean side that served as a no-go reminder. Should your golf ball go over the fence and plop down in front of one of the munitions storage bunkers there, you might have to kiss it goodbye. However, by the fences were long poles with a circular ring on the end. If it reached your mis-hit ball, you could retrieve it. If the pole couldn’t reach your ball, you were SOL.

There was not the same problem at Kwajalein’s golf driving range. There was no way you could lose your golf ball there. That’s because the range had repurposed an enormous and abandoned circular radar structure. The radar’s construction had created a giant circular steel mesh so tall, and with such a large diameter, that no matter how hard you might hit a golf ball from the radar’s perimeter, you couldn’t knock it out of the enclosed space. This was no doubt the most expensive golf driving range ever built by mankind.

On one of our golf outings by the runway our play was interrupted by loud klaxon horns atop the many radars on the greensward. “What the hell is that?” I asked. My minder said that it was a warning that powerful, potentially harmful radar waves would soon be sweeping our fairway or perhaps there was a danger of debris from an incoming or outgoing test missile, and we needed to immediately take shelter. Believe me, he didn’t have to tell me twice!

One evening after dinner I strolled down to the small harbor at nightfall. It was quiet and peaceful looking out at the lagoon. Soon I noticed another man out for an evening stroll. We struck up a conversation and I asked him what he did on Kwajalein. He said he was just visiting from California and that he was looking forward to the incoming ICBM later that evening. That was news to me, so I asked him how he knew about that. He said that he was the person who had programed the instrument package that replaced the ICBM’s warhead for the test. He said this was his first opportunity to see the fireworks above Johnston as the incoming missile and his package headed through the atmosphere to preprogrammed coordinates in the lagoon. I quickly decided I too would stay up late for the fireworks. Sadly, when I woke up the next morning, I had to kick myself for sleeping through the night and missing the big show.

One of the issues that surfaced in my later counterintelligence report had to do with a Soviet spy ship, disguised as a fishing trawler. It permanently lingered just outside the Atoll in international waters. There, it constantly monitored the telecommunications of all the personnel on Kwajalein, as well as the telemetry of every rocket test. Besides the communication security protocols in place to minimize the value of the trawler’s signals intercepts, another very important procedure related to the spy ship had been put in place. When an incoming instrument package had separated from its ICBM and fell into Kwajalein’s lagoon, at least three splash detection radars at different points on the Atoll would triangulate the precise location of the splash. This permitted an assessment of whether the accuracy of the missile launch was sufficient to destroy a hardened Soviet ICBM silo in the U.S.S.R. In a further security step, swimmers would immediately dive into the lagoon at the impact point and recover the instrument package and its data. This was a protocol to ensure no divers from the Soviet intelligence ship would ever beat them to the punch.

When the Congressional folks who had delayed my work hit the road, I caught the first available twin-engine commuter flight up to nearby Meck Island on the Atoll. Here was Safeguard’s recently constructed Phased Array Radar that I needed to understand better. The large radar had a fixed and circular slanted face that permitted it to scan incoming missiles launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Air Force crews, plucked at random from Montana or other ICBM installations, would be trucked with their Minuteman missiles to Vandenberg. At Vandenberg, their launch proficiency would be tested, and the missiles were regularly topped off with instrument packages instead of warheads before being launched at a predetermined point in Kwajalein’s lagoon.

As the Meck Island manager took me into the outsized computer room that formed the base of the large radar, he smiled, and, in a voice like that of a proud father talking about a child bringing home a good report card, he said that there was more computing power in that room than existed on the entire planet in 1955. As I digested the meaning of that, the thought occurred to me that he might in fact be telling me the truth.

From Meck, I flew up to Roi-Namur Island on the north end of the atoll. There were different radars and instrumentation issues I needed to learn about at that location as well. With my fieldwork complete, I was ready to go home to Washington, D.C., and write my report. I quickly caught the last commuter flight of the day at Roi-Namur and flew the 50 miles south back to my Bachelor Officers Quarters (BOQ) accommodations on Kwajalein Island. Without delay, I was on the next red-tail Northwest jet that came through Kwajalein to shortly begin a week’s leave from the Army in Honolulu visiting a college classmate and his family.

Upon my return to the Pentagon, I spent several weeks doing further research. Then I turned for several more weeks to writing up my report on the Safeguard System’s espionage and sabotage vulnerabilities and the steps necessary to further harden the System’s operational weaknesses. In late fall 1969, I completed my assignment by providing briefings on my report to the Safeguard Security Working Group, other senior Army officers, and various civilian technical and scientific advisers.

My effort must have met with approval as the Commanding Officer of the 902nd Military Intelligence Group awarded me at year-end a Certificate of Achievement for “exemplary duty” for this work. To me, that meant that the report had probably been more useful than anyone had imagined it would be when I was first assigned the task.

Kent State University and the Aftermath