Subchapters

- Jane Byrne vs. The Chicago Tribune

- The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

- Mayor Byrne’s 90-Day Report Card

- Mayor Jane Byrne’s Secret Transition Report

- Rob Warden

- “Innuendo, Lies, Smears, Character Assassinations and Male Chauvinist”

- Rally ‘Round the First Amendment

- Will She or Won’t She?

- The Aftermath—Harold Washington Defeats Jane Byrne

The Machine Weakens after Daley’s Death

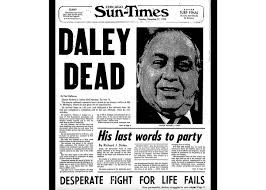

Richard J. Daley Dies

With the

anti-Daley vote thus split, Daley was reelected in the Democratic primary election in February 1975 with 58 percent of the vote. Singer came in second with 29 percent, Newhouse with 8 percent, and Hanrahan 5 percent. In a striking change to the usual playing field, Daley’s share of the vote was much smaller than in his earlier races for mayor. And this time, he also won less than half of the African American vote. This portended the fundamental shift that finally occurred when Harold Washington spoiled Jane Byrne’s shot at a second mayoral term and was elected Chicago’s first African American mayor in 1983.

Shortly following Daley’s death in 1976, mourners had an opportunity to pay their respects by passing his casket as it lay in state at the Nativity of Our Lord Catholic Church in Daley’s home ward. An estimated 100,000 came to this church in Daley’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The mourners included political figures such as Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, President-elect Jimmy Carter, and U.S. Senators Edward Kennedy and George McGovern. Those paying their respects also included political opponents. Both myself and my then-brother-in-law Bill Singer stood in the cold in the long line waiting access to the church that day.

Daley’s death was followed by a six-month interregnum during which a number of City Council aldermen jockeyed for supremacy. The upshot was that Michael Bilandic, the 11th Ward Alderman of Daley’s home ward, was elected later in 1977 to fill out the remainder of Daley’s term of office.

Although Bilandic had inherited Jane Byrne from Daley as the city’s Commissioner of Consumer Affairs, she didn’t last long. When Bilandic supported an increase in taxi fares, Byrne not only refused to say it was a needed adjustment, but she also denounced it as a harmful “backroom deal” that Bilandic had “greased.”

That was it for Jane Byrne, who was promptly fired from her job by Bilandic in November 1977. When Byrne announced four months later that she would run for mayor against Bilandic, almost no one took her as a serious threat to his upcoming reelection bid in the February 1979 Democratic primary.

The transition report had been undertaken at Byrne’s request shortly after she defeated sitting Mayor Michael Bilandic in the Democratic primary election in early 1979. A prominent member of her transition team was longtime independent City Council Alderman Dick Simpson. Simpson had graduated from the University of Texas in 1963 and then pursued a doctorate degree with research in Africa. He started a teaching career as a political science professor at the University of Illinois Chicago in 1967, the same year I graduated from the University of Chicago’s Law School.

Off the teaching clock, Simpson became a co-founder of Chicago’s Independent Precinct Organization (IPO) and served as its executive director. The IPO was a body of lakefront liberals focused on good government. In its case, this almost always meant serving as a not-very-heavy counterweight to the dominant machine politics of Mayor Richard J. Daley, head of the Regular Democratic Organization in Chicago’s Cook County. I had gotten to know Simpson from my political work with Singer.

Health had been a minor issue in Daley’s 1975 mayoral campaign and, the year after his reelection as mayor, the 74-year-old suffered a heart attack in his doctor’s office and died on December 20, 1976.

Dick Simpson

My work on the Singer mayoral campaign had permitted me to get to know Dick Simpson better and, just before Daley died, Simpson told me he was interested in promoting the idea of greater citizen involvement in ward zoning decisions.

He explained how he envisioned community zoning boards might work and asked me to draft an ordinance that would detail their creation, structure, and operation. While I had written plenty of speeches and press releases by that time, I had never taken on the task of drafting a piece of legislation of this complexity. It struck me as an interesting technical challenge, and I told Simpson I’d give it a shot.

This was notwithstanding my own serious doubts about the wisdom of such a radical decentralization of land-use regulation in the city. Then and now, the existing primacy of aldermanic prerogatives in zoning gave aldermen what amounted to a practical veto over many zoning decisions and had engendered widespread aldermanic corruption.

However, it wasn’t clear whether Simpson’s idea was likely to fix that problem or make it worse by encouraging more parochial NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) decisions that shorted the best interests of the city as a whole.

Simpson was pleased with my handiwork and introduced my draft of his ordinance for consideration by the full City Council in early 1977. As was usual with any initiative of one of the independent Democratic aldermen, it was never seriously considered.

I first met Singer in the summer of 1966 after my second year of law school. I was serving then as a summer clerk at the Ross, Hardies, O’Keefe, Babcock, McDugald & Parsons law firm in Chicago. He had already started there as a new associate lawyer recently graduated from Columbia Law School. After my law school graduation in June 1967, I passed the bar exam and joined Singer as a full-time associate attorney at the firm until I entered the Army in May 1968.

Then in late 1968, when Bill learned I was going to be stationed at the Pentagon in Washington, he suggested I look up his wife Connie’s sister, Judy Arndt, then working on one of the Congressional staffs. I took him up on his suggestion. As fate would have it, a few years later Bill and I were briefly conjoined as brothers-in-law. This temporary state soon ended as the two sisters were divorced from the two Bills.

Aldermen Dick Simpson, Leon Depres, and Bill Singer

During my time in the Army from 1968 to 1971, Bill had started a successful political career while continuing to practice law. In 1969, as I was settling into my Army work dealing with its newly created civil disturbance mission, Dick Simpson was managing Bill’s winning campaign to be elected an independent Democratic alderman of the 44th Ward in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood.

Later in the decade of the 1970s, the Regular Democratic Organization under Daley had the ward maps redrawn in hopes of squelching Singer’s independent political movement. Nonetheless, Singer was elected in the newly redrawn 43rd Ward and Dick Simpson became 44th Ward Alderman. Both men were constant and articulate critics of the Daley era’s centralized control over the politics of both the City and Cook County. They were up against powerful headwinds, as Daley’s wildly successful patronage-based political organization wasn’t called the “machine” for nothing.

Before I left the Army in 1971, another Ross, Hardies associate, Jared Kaplan, had called me from Chicago to say he was coming to Washington on business and would like to have lunch. I invited him to join me for a sandwich in the Pentagon’s central courtyard, then open to civilian visitors. During lunch, he told me that he, Bill Singer, and some other Ross, Hardies lawyers would shortly be leaving the firm to start a new smaller law firm. He wanted me to join them.

1972 Bill Singer

At the time, I was turning 28 and felt that my time in the Army had put me behind my law school contemporaries in pursuing my legal career. Almost all of them had been able to pursue their legal careers without a three-year interruption for military service. At the time, I was having a hard time remembering what if anything I had actually learned in law school. I thought that, though it would be riskier to turn down my standing offer to rejoin Ross, Hardies, joining a startup firm would likely give me more experience and responsibility sooner in the practice of law.

My thinking was that this would also let me catch up to my peers sooner than if I were to go back to a larger, more structured law firm. With the die cast, I left the Army in spring 1971 to practice at the newly established law firm of Roan, Grossman, Singer, Mauck & Kaplan (later Roan & Grossman). Not returning to Ross, Hardies turned out to be fortuitous for me as the firm shortly thereafter was forced to lay off most younger lawyers after its largest client, Peoples Gas Co., decided to fire the firm and create its own in-house law department.

Bill Singer, while 43rd Ward Alderman and a partner at the new Roan & Grossman law firm, had joined with Jesse Jackson and other liberal anti-machine forces to successfully challenge the seating of Richard J. Daley’s delegation of regular Democrats at the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami. This success and attendant publicity led Singer to give thought to challenging Daley in the mayoral Democratic primary race to take place in February 1975. Singer announced his candidacy on October 15, 1973, leaving himself a full 18 months to raise funds and campaign throughout the city.

During this period, Singer asked me to become Secretary of his 43rd Ward organization, and later, as his campaign picked up steam, to join the campaign full time. Being eager to take on the challenge of what I thought was a worthy battle, I took a leave of absence from Roan & Grossman and became General Counsel and Director of Research of the Singer mayoral campaign. As the campaign grew more frantic and Singer’s time got stretched thinner, I also began writing occasional speeches, campaign statements and press releases, as well as position papers on various issues of the day.

During the Singer campaign in 1974-1975, I had met Don Rose, a longtime anti-machine and civil rights activist. Later, in 1979, I briefly sought his advice as I launched an unsuccessful effort to defeat the current machine Democratic Committeeman for the 43rd Ward. I don’t remember the advice Don Rose gave me, but it wouldn’t have mattered one way or the other.

As it turned out, I was tossed off the ballot for having insufficient signatures on my nominating petitions. I successfully appealed this decision of the Cook County Board of Election Commissioners, and the Illinois Appellate Court ordered my name back on the ballot. However, when the dust finally settled, I could tell people I’d lost the election by only seven votes. Unfortunately, these were the votes of the seven Illinois Supreme Court justices who reversed the Appeals court. Thus, was short-circuited my ill-fated political career.

Though usually working behind the scenes, over the years Rose had a number of important roles in the city’s electoral contests and political spectacles. In 1966, Rose had served as Martin Luther King Jr.’s press secretary when King moved into a Chicago slum to bring attention to poverty and racial injustice in the North as part of his Chicago Freedom Campaign. Apart from handling the local press in this effort, Rose served as a King speechwriter and one of his local strategists. He later looked back on this effort as probably the most important thing he ever did.

Two years later in fall 1968, Rose had a major role in the circus around the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The resultant street battles with police immediately preceded the opening of the Democratic National Convention. The following year, my law school classmate Bernardine Dohrn and her fellow radical, Bill Ayers, were busy organizing the Days of Rage riots of the Weather Underground. I was watching all this unfold with more than casual interest given my role at the Pentagon at the time in assessing whether civil disturbances might grow.

2022 Don Rose

Coincident with the Convention unpleasantness, the “Yippies” had also arrived in Chicago for the Convention with their political theater of nominating a pig for president. However, SDS and the Yippies were just the opening act in 1968. The bulk of the anti-war demonstrators had come to town by the thousands under the aegis of the coalition of groups known as the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam; the MOBE for short. And Don Rose, building on his recent successful effort for Dr. King, became the press spokesman for the MOBE and was credited with creating the slogan of the anti-war demonstrations, “The Whole World is Watching.”

A committed man of the left all his life, Rose could manage to work for a Republican if the times called for it. He took particular pride in his management of the campaign of Republican Bernard Carey in 1972 against the sitting Cook County State’s Attorney, Edward Hanrahan. Hanrahan had been vastly weakened with the public as a result of his deadly raid on Black Panther leader Fred Hampton’s house in late 1969. Most people thought the raid was a botched one at best and a murderous one at worst.

I personally felt so strongly about it that I and Ross, Hardies lawyer Phillip Ginsberg had earlier called upon the Chicago Bar Association to initiate a breach of legal ethics investigation against Hanrahan.

1999 Don Rose and Sun-Times political reporter Basil Talbot 1999

Notwithstanding the Hampton scandal, when Hanrahan came up for reelection, he was still the machine candidate and widely presumed to be a winner. That’s when Don Rose arrived and helped Carey win what would normally have been a losing matchup.

Chicago Tribune contributing Sunday editor Dennis L. Breo captured a profile of Rose in a 1987 portrait. When I recently reread the article, I was struck by the fact that I had a relationship of one sort or another with all of those he quoted talking about Rose. Basil Talbott, political editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, was a friend I knew from politics and Lincoln Park, Mike Royko of the Chicago Tribune had written a column about my uncle, Judge Augustine Bowe, when he died. Also, as a widower Royko had later married my first wife, Judy Arndt. Ron Dorfman was a friend and the journalist who founded the Chicago Journalism Review in 1968. At the end of his life, he beat it to death’s door by becoming half of the first gay couple to marry when Illinois law changed in 2014. The last to be quoted was my former law colleague and brother-in-law, Bill Singer. While I was only casually acquainted with Rose, we had many other friends in common.

With a long history of civil rights and anti-Daley, anti-machine credentials, Rose again was available for a battle against the machine in 1979 when Jane Byrne looked to all like a quixotic loser up against Daley’s successor Bilandic.