1995 Britannica Online

The Building of Britannica Online

By Robert McHenry

Former Editor-in-Chief, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Introduction

Had someone back about 1985 phrased his question, wittingly or not, “Has the Britannica been digitized yet?” the answer would have been “Yes, and in fact we’re already on our third computer system.” Publishing an annual revision of a 32,000-page encyclopedia is a major undertaking, and the development of computer-based systems for handling this huge amount of data promised similarly major economies.

The text of the encyclopedia was first digitized – keyed into a digital database – about 1977; the data fed an RCA PhotoComp photocomposition device that produced the page film from which offset printing plates are created. In 1981 the data was ported to a more powerful Atex system, a system mainly used by newspapers because it offered a very robust set of editing tools. But when a full revision of the encyclopedia was undertaken – one in which every page in the set would have to be recomposed, rather than the 1,000 or 2,000 that had been typical for some years – Atex proved inadequate. It was replaced in 1984 by the Integrated Publishing System, or IPS, a purely software solution developed by the Watchtower publishing arm of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

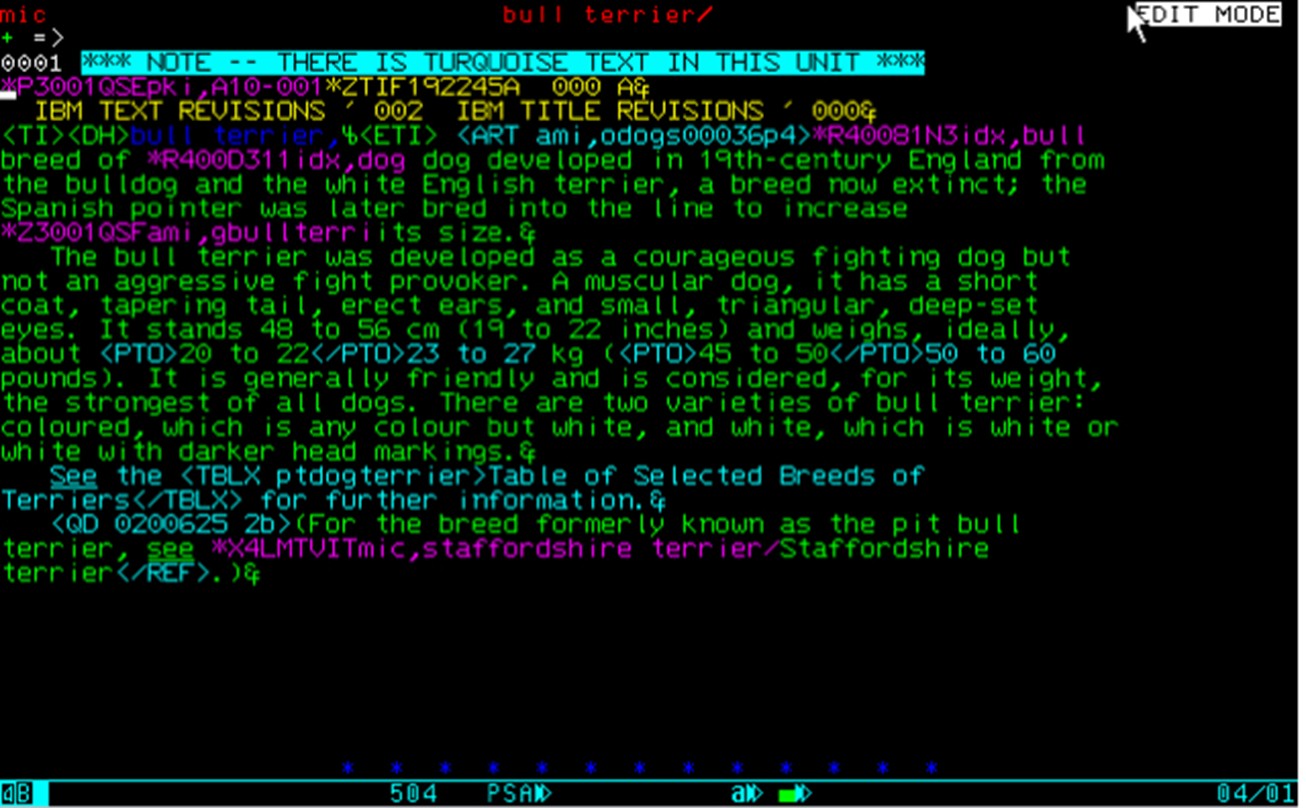

Because Watchtower carried on a very heavy publishing program in 60-odd languages it had taken the initiative to develop a system with good editing tools and a WYSIWYG composition engine and one that natively handled a very large set of alphabetic and symbolic characters. Marketing, licensing, and support for IPS were handled for the Witnesses by IBM, on whose mainframe it was designed to run. Having installed IPS, Britannica’s Editorial Computer Services group undertook a program of customization, adding such features as hyphenation and justification, a spell checker, and various editorial management tools. The editing segment of IPS, called PSEdit, used a text markup system that, while proprietary, was sufficiently SGML-like that in time it proved readily convertible to that system or to HTML. (Less readily convertible was PSEdit’s use of color and reverse video as meaningful attributes.) A typical short Britannica article, displayed on an editing screen (an IBM 3079 terminal) looked like this:

One unique and essential bit of customization added by the ECS group was a method of inserting metatext tags, called hooks, into text articles and linking them in such fashion that they behaved analogously to what later came to be called hyperlinks. These tags were used in a variety of ways: to link illustration files and their related caption files to points in article text; to connect cross references with their referents; to connect groups of topically related articles with the outline of topics in Britannica called the Propaedia; and, most numerously, to connect terms and their citations in the Index with the actual points in text from which they had originated and to which they pointed back. In the graphic above, the pink strings are the hooks. The Index hooks and Propaedia hooks would later be exploited in Britannica Online to produce an elaborate navigation system over the whole body of 65,000 articles.

The task of “surfing” the Web, as it was already known, looking for informative and authoritative sites on an encyclopedic breadth of subjects fell to the editor in chief of Britannica. He originally asked for a budget variance to permit the hiring of a temporary editor for the summer but was turned down. Such external links, opined the senior manager who denied the request, were not going to be an important feature of BOL.

In the event, by the locking-down of the data in preparation for the September release, 398 links to other Web sites were appended to a slightly smaller number of encyclopedia articles (a few having two or more such links). The surfing method relied heavily on the Virtual Library that had been created at the mother Web site at CERN, which provided a topically organized set of URLs from which to begin. It is perhaps worth remarking that even at that early date the city of Hoboken, New Jersey, had a Web site.

Part I

From the middle 1980s people who were in some way associated with the Encyclopædia Britannica began to encounter the question “Is the Britannica available on the computer yet?” or, a little later, “When will Britannica be available on CD?” The questions, infrequent at first, became increasingly insistent as the ’90s opened and the CD-ROM format became more widely familiar. Many people now believe that they remember seeing Microsoft’s Encarta CD-ROM encyclopedia in 1990 or 1991. In fact, Encarta on disk debuted in 1993 and was neither the first encyclopedia on CD-ROM – that had been the DOS-based text-only Grolier’s in 1985 – nor the first multimedia encyclopedia on CD-ROM – that was Compton’s MultiMedia Encyclopedia (a Britannica property) in 1989.

By the late1990s the question had mutated to “Is Britannica online yet?” The answer, which surprises some people to this day, was “Yes, and in fact it was the first such reference resource available on the Internet.” That Encarta was able to dominate the market for CD-ROM encyclopedias from the moment of its entry is attributable to Microsoft’s exhaustless funds, market position, and casual disregard for quality work. That Britannica’s early coups should be so little known is attributable to factors beyond the scope of this essay, but chief among which was the inability of the company’s senior management to embrace electronic publishing and pursue it forcefully.

With the benefit of hindsight, a surprising number of people now claim fatherhood or motherhood of Britannica Online. A quick online search will turn up several of them. When some scholar finally undertakes to write a full history of the modern Britannica company, others will doubtless pop up. Lest their versions of history become too firmly embedded as conventional wisdom, I have compiled the following sketch of the genesis and early development of Britannica Online, focusing entirely on the people who actually created it, who had the ideas and did the real work, and who, when the company had finally lost not only its early leadership but its sense of direction, could only look back wistfully at what was one of the most rewarding episodes in their careers.

Background

Corporate Environment. From its formation in the 1940s until 1995 or so, the modern Britannica company existed in a state of tension, sometimes creative and sometimes not, between two roughly coequal parts, the editorial operation and the sales operation. Sales was intrinsically the stronger of the two, because it was the source of funds and growth and because so many senior company executives came up through the sales organization. The editorial side was able to hold its own chiefly because of the extraordinary influence which Mortimer Adler exerted. A separate essay might be written on the powerful personality of Adler; suffice it here to note that he had the ear of successive chairmen of the Board of Directors and the support of most of the Board and of significant outsiders.

The sales organization was built upon in-home direct sales. It was an article of faith that a high- ticket discretionary-purchase product like an encyclopedia could be sold in no other way, or at least not in the volume required to support the enterprise. The field sales force used leads, some generated by local marketing but most generated by the company through national advertising and other means (and powered by a budget that exceeded the editorial budget), and for nearly every sale sent back to the company a time-purchase contract and a small down payment. The salesman, his district manager, that manager’s regional manager, and the sales vice president next up the line all collected a commission on the sale. The cost of the goods (in 1990 roughly $300) and the cost of the sale were financed on the future payments receivable. One result of such a highly leveraged system was a relentless drive to recruit more salespeople, in order to produce more receivables. Another result was an inordinate sensitivity on the part of senior sales executives to what they judged to be the mood and morale of the field force.

Senior management was, nonetheless, not unaware of the revolution in information technology that began to affect the consumer market in the 1980s. While the Britannica and its text were off limits (with one exception), the company had another product with which to experiment, the Compton’s Encyclopedia. Compton’s was intended for young readers and was used almost exclusively as a premium in sales of the senior set. The editorial cost of maintaining Compton’s was, in effect, a promotional expense. It was believed that the sales force would have no objection to using the Compton’s name and content in electronic products.

CMME. In 1987 Britannica was approached by Educational Systems Corporation, a San Diego company that was building a networked classroom study resources system for schools and wanted to include a CD-ROM encyclopedia in the package. Britannica refused to make the EB text available and offered Compton’s instead. With even that lesser amount of text to deal with, ESC realized that it would need also a text-search engine of some sort. For that they approached the Del Mar Group, a small company founded by Harold Kester, which had just such an engine.

The Del Mar Group’s engine, called SmarTrieve, was arguably the most accurate and efficient such engine then available outside a research laboratory. In the contract signed in March 1988, Del Mar Group not only licensed SmarTrieve to ESC for use in the school product, but it also undertook to handle the parsing of Compton’s text and to design the overall data structure for a CD-ROM-based multimedia encyclopedia, including graphics and audio and video segments. The data-structure design, authored by Kester and Art Larsen, was apparently the first of its kind and later was a core element in the disputed Compton’s patent.

Compton’s MultiMedia Encyclopedia (CMME) was first demonstrated publicly in April 1989 at an educational conference in Anaheim, California, by Greg Bestick of ESC, now called Josten’s Learning Corporation. In a year-end wrap up, Business Week magazine dubbed CMME one of the top ten new products of the year. Britannica, having retained the right to market CMME in the consumer market, began selling it the following year. The original version, tailored to Radio Shack’s Tandy computer, was followed in 1991 by a Windows version and a short time later by a Mac version. During this same period (I have so far not found the exact date) an agreement was made to license Compton’s digitized text to Trintex, a consumer-oriented information service running over a proprietary network. (Trintex, after the withdrawal of one of its three original partners, became the Prodigy service.)

Electric Britannicas

The Early Disks. While CMME was still in its initial development phase, Kester set his sights on the EB text. At Microsoft’s CD-ROM Expo in February 1989, he had showed an executive of Britannica Learning Corp. how the digitized Compton’s data, running under SmarTrieve, could almost instantaneously yield an answer to the query “Why do leaves fall from trees in the autumn?” In September he demonstrated the SmarTrieve technology at the Chicago headquarters of Britannica, and the following month he secured an agreement under which he was given access to the EB text data. As he recalls, it took his two IBM 80286 computers some three months of continuous processing to parse the whole of the EB text (into a proprietary format dubbed BSTIF, for Britannica Software Tagged Interchange Format) and produce the inverted index. But while this provided him great satisfaction, it was of only secondary interest to Britannica at the time. In March 1990 Britannica purchased the Del Mar Group, and with it the rights to SmarTrieve, and folded it into the Britannica Software division (renamed Compton’s New Media in 1992). Priority was given to the development of the consumer CMME for various platforms and to an ambitious program of consumer CD-ROM publishing, ranging from the Guinness Book of Records to the Berenstain Bears.

The search for an application for the EB data, one that could be done as if it were in spare time and that would not alarm sales management, led to the Britannica Electronic Index, or BEI. BEI ran in DOS and was essentially the SmarTrieve index of EB data on a CD-ROM. A typed-in query would yield a relevance-ordered list of references to the text in the form of volume-page- quadrant citations. (Sidebar 3) For the user, BEI was supposed to function as a super index, far surpassing even the two-volume printed index in comprehensiveness and, unlike a printed index, able to deal with queries involving more than a single term. As a product, it was a giveaway – yet another premium item used in hope of promoting sales of the print set.

The first true electronic Britannica product arose in part from a spate of publicity generated in mid-1991 by critics of certain high school history textbooks, which had been found to be rife with factual error. It emerged that most textbook publishers relied on outside service vendors for such fact-checking as was done in the development of textbooks, and often none was done at all. Fact-checking is slow, tedious, and difficult. An electronic product with sophisticated search- and-retrieval capabilities running over a superior text base could make the process more effective and cost-efficient. From this insight proceeded the notion of the Britannica Instant Research System, or BIRS (at first known internally as “Fact Finder”). Intended for the professional user, BIRS ran under Windows 3.0 and consisted of two CD-ROMs, one containing the SmarTrieve indices and the other containing the Britannica text. The contents of both disks were to be transferred to the user’s PC hard drive, which had thus to be of 1-gigabyte capacity, very large and very expensive for the day. BIRS was introduced in June 1992 with what was for Britannica substantial fanfare, but it was bought by only a very few venturesome customers, including the small Evanston, Ill.-based editorial service company that had served as the beta site.

“Network Britannica.” While managing to see BEI and BIRS out the door, and thereby allowing the nose of the camel into the tent, Kester had been pressing for an independent budget to support research into how the core Britannica data – not only text but indexed and classified text – could best be exploited electronically. He assembled a team, the main members of which were John Dimm, already at Britannica Software by way of ESC; Bob Clarke, a consultant and freelance seer whom Kester had worked with in the earliest days of the Del Mar Group; John McInerney, whose experience lay in network administration and security; Rik Belew, a professor of computer science at UC San Diego, who served as a part-time consultant; and two doctoral students from his department, Brian Bartell and Amy Steier. By late 1992 these formed a separate, and somewhat isolated, group within Compton’s New Media, and it was formally organized as the Advanced Technology Group in April 1993. In August 1993, the ATG moved out of the Compton’s offices in Carlsbad, California, and opened its own office in La Jolla, near the UCSD campus. Mention must also be made here of an honorary member of ATG, Vince Star, who oversaw the Britannica publishing system in Chicago and had thus been responsible early on for preparing text data for transfer to the West Coast group. The introduction of email in the Chicago office in early 1993, at first and for some time on a very limited basis (limited not merely by resources and a learning curve but also by the fact that it was “elm” mail, a UNIX application for which one had to learn some rudiments of a clumsy editor called “vi”), had the effect of cementing relationships between ATG and a few committed hands at headquarters.

The earliest and thereafter driving goal of the ATG team was set by Clarke, who forcefully held out the assertion of Scott McNealy (he of Sun Microsystems) that “the network is the platform.” This could actually be taken in two ways, and Clarke argued both: First, “the” network – the Internet – was the emerging standard; second, as a development strategy, solving the hard problem first – building what he called System Britannica, essentially a networked version of Britannica – would lay a solid foundation from which to derive CD-ROM and other versions.

Thus, what was finally released as the Britannica CD 1.0 (known simply as BCD) in 1994 was in effect the network product ported to a disk for use in a PC that was both server and client.

The problems were many. Britannica text included a great many “special characters,” including letter forms and diacritics used in non-English words (often proper names), mathematical symbols, and scientific notation. Translating raw Britannica text into ASCII or into the larger but still limited character sets used in Windows and other platforms was difficult and error-prone, and the results were judged unsatisfactory by the Britannica editors. These transliterations also compromised the accuracy of the indexing done by the search-and-retrieval software. Large portions of mathematics and science articles (such as complex formulae or chemical diagrams) in the set had been created as “special comp” for the printing process – essentially pieces of artwork that had no counterparts in the digitized text database and thus left “holes” when the text alone was used. Much other artwork of a more conventional sort was considered essential to supplement the text.

On the technical side the problems were equally challenging. The raw text was huge – just over 300 Mb – and consisted of tens of thousands of separate files, a number that jumped once the Macropaedia articles, some of which ran to upwards of 250,000 words, were split into manageable chunks. Then there were the questions of which networks to design for, for what download speeds, and for what sorts of display? Windows had not yet penetrated the network market in any significant way, and the most common machines used for data display were the VT100 “dumb terminals.”

Beyond matters of implementation were larger questions, to which Clarke, in particular, was giving much thought: What truly innovative products and what wholly new methods of information representation and use might arise from learning how to exploit the indexing within Britannica and the subject-classification codes that were used to tag the text? In a network environment, what relationships might obtain or grow up between the content of Britannica and other information resources on the network?

Annus Mirabilis: 1993. An unexpected stimulus to ATG’s efforts occurred in January 1993, when the Editorial Department at Britannica was approached by representatives of the University of Chicago, who proposed to help develop a LAN-based version of Britannica to run on the campus network. The University already had amassed considerable experience in dealing with large textual databases, notably the ARTFL archive of documents in French literature.

Discussions continued for a few months, and a bit of prototyping was done, but in the end the proposal came to naught. The useful results of the episode were three: a demonstration in which some Britannica text on a university server was accessed via dialup connection from the EB Library and displayed on a PC in glorious green ASCII; credibility for the proposition that there might be a market for a networked Britannica product among colleges, libraries, and other institutions; and, in one of the earliest of the meetings, a mention of the word “Internet,” heard then and there for the first time by the Britannica side.

From the outset Chicago and La Jolla took quite different approaches to conceiving Network Britannica. In Chicago it seemed natural to assume that the product would employ wholly proprietary software. In La Jolla the ideas of easy exchange of information, open standards, and off-the-shelf applications held great appeal. John Dimm, who had first-hand experience in developing the various flavors of the Compton’s CMME and was therefore intimately familiar with both the difficulty of the platform-specific approach and the brittleness of the results, was especially ardent in championing the adoption (and adaptation as needed) of available and proven solutions. It is also worth remembering that even given development focused on LANs, provision had to be made for dialup connection as well, which at the time meant, at best, 9600 baud transfer rates.

The first concrete step in the direction of general solutions was the decision to abandon SmarTrieve in favor of the WAIS search engine. WAIS (Wide-Area Information Server) had been introduced two years earlier as the first full-text search engine capable of running over multiple, distributed databases. Contact was made with the WAIS office in Mountain View, California, and in a short time a formal agreement was reached for code-sharing. A WAIS staff programmer (Harry Morris) who was already at work on version 2 of WAIS was the main liaison with ATG, working chiefly with Brian Bartell and Amy Steier. Steier’s work involved developing software able to recognize phrases in English text and treat them as fixed units for indexing and retrieval. Bartell sought to improve the estimation of relevance by the retrieval engine by incorporating into its logic a number of “experts” sensitive to certain conditions, such as the occurrence of a search term in a document title, or multiple occurrences within a document, or occurrences early rather than late in the document. (A minor byproduct of this business association was an invitation to WAIS’s founder, Brewster Kahle, to speak at the Britannica Editorial Convocation in October 1993, where Vince Star and his colleagues memorably appeared sporting propeller beanies.)

On April 14, 1993, the “eb.com” domain was registered with InterNIC, largely at Clarke’s instance. Chicago was far from accepting the Internet as the platform for Network Britannica, but ATG was forging ahead, protected mainly by the 1,723 air miles separating them from the home office.

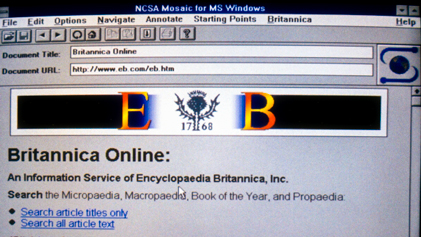

Up to the summer of 1993, Dimm was proposing that Adobe Acrobat be adopted as the document viewer for Network Britannica. The choice of Acrobat was in line with his view that established and widely used software was preferable to a proprietary solution. Acrobat, which provided page views of documents, would solve the problem of displaying formulae and the like, though not that of capturing them in the first place. As it happened, Britannica was at that point considering Adobe, among others, as a supplier of a new system to replace IPS. In the end, neither came to pass. Dimm gave a presentation at a computer science class at UCSD and there saw a demonstration of the World Wide Web, using Tim Berners-Lee’s original browser. Shortly thereafter, in June 1993, he saw a pre-alpha-release version of Mosaic at the American Booksellers’ Convention in Miami. He immediately began plumping for the Web as the platform and Mosaic as the viewer for Network Britannica. By the time Mosaic was first formally released, in version 0.5a in September, the challenges of data conversion and making WAIS Web- and Mosaic-compliant were already in course of solution.

A large sample of EB data was parsed (from BSTIF) into HTML in November and was browsable by means of Mosaic. By early December the whole article database was up and running. Bartell and McInerney had written a cgi (common gateway interface; a standard piece of coding later but a bit of rocket science at the time) program to link Mosaic, WAIS, and the document collection. (Special characters were still a problem; one exchange of emails concerned the all-important (for Britannica) “æ” character.) McInerney had built the necessary servers and firewall and had created a user-authentication system based on users’ IP addresses. At a time when such was still possible, McInerney communicated directly with Marc Andreessen at the NCSA center in Champaign, Illinois, where Mosaic was under development, on getting the WAIS-HTML gateway to function properly.

The result was an application that invited the user to type in one or more search terms, which were then processed by WAIS in order to produce a relevance-ranked list of document references. These references were then presented in a Web page, created on the fly, with links directly to the documents, which were Britannica articles or portions of articles. In subsequent development this “hit-list” page featured a brief extract of each document (to enable the user to make a more informed selection), while the returned article showed the search term(s) in boldface.

In the second half of December the firewall was cautiously opened to a few people outside the ATG office, who were invited to look in it.

Rik Belew was able to browse Britannica articles from his campus office, as was a key contact at the UCSD library, and Vince Star logged in from Chicago. The first semiformal demonstrations took place in what we may as well call the

Mensis Mirabilis: January 1994. During this month there occurred the first demonstration to the Chicago editorial staff of EB Online, now given management’s very quiet blessing as “Britannica Online.” A demonstration to Rik Belew’s computer-science class on January 14 and another four days later to staff members at the UCSD library ended the quiet. No version of Britannica Online was ever declared the official alpha release, but had there been one it would have been the version used in these two demos. Word spread very quickly, and by early February the UCSD library reported being inundated with requests for access to BOL. For the Belew demo, John Dimm added a link at the end of the article “Vatican Museums and Libraries” to the Library of Congress’ experimental “Vatican” exhibit (hosted on the University of North Carolina’s very active “sunsite”). This was the first of what came to be called “external links” and later “Related Internet Links,” or RILs, in BOL. Also, in time for the Belew demo, Dimm implemented a system of internal linking from classified lists of related articles (in the Propaedia outline) to the articles themselves, thus enabling topical browsing. On January 20, Dimm sent an email to the product management group in Chicago containing the HTML for an alpha-level public home page for Britannica Online. At the very bottom of the page, he copied over the standard publisher’s information from the printed title pages of every Britannica volume, slyly adding “La Jolla” after “Chicago” in the list of the company’s principal operating centers.

On February 8, following an announcement by a senior Britannica officer at the American Booksellers’ Convention in San Francisco, an article by technology reporter John Markoff appeared on page 1 of the Business Section of the New York Times, headlined “Britannica’s 44 Million Words Are Going On Line.” The cat was truly loose; McInerney immediately began recording hundreds of hits on the firewall protecting the data. Beta testers were recruited at various universities (Nancy Johns at the library of UIC, in Chicago, was notably enthusiastic; also involved were faculty or staff from Stanford, Dartmouth, and ??), and volunteer testers began showing up as well. One, known simply as “Larry” and evidently based in the computer science department of the University of Idaho, discovered BOL and promptly added a link to it from his own home page, which otherwise featured graphics inspired by Metallica and other favored bands. His link read simply “a pretty good encyclopedia.” By contrast, “Joel,” at the University of Illinois, quickly adapted the outline scheme of the Propaedia in BOL for a project of his own and had to have something of copyright law explained to him by Britannica’s legal department.

From February until the formal release of Britannica Online 1.0 in September 1994, the work of ATG and of those involved in Chicago was chiefly refinement of the concept. The Indexing group of the Editorial Department was recruited to run exhaustive tests on the WAIS search engine, their results then being used by Bartell and Steier to fine-tune the proprietary “experts” that weighed the relevance of responses to queries. Vince Star wrote the parser that produced HTML documents directly from the PSEDIT data, thus eliminating the awkward and “lossy” intermediate step involving BSTIF. The special character problems were largely solved (though mathematical expressions continued to be difficult to manage). About one-tenth of the illustrations in the print set, some 2,200 in all, which had been determined by the editors to be essential to a full use and understanding of the text, were captured digitally and linked to their proper locations in the articles. The index hooks in the PSEDIT data, linking points in article text to entries and citations in the printed Index, were in a later parsing converted to href tags in the HTML data, thus creating a network of some 1.2 million internal links through the text of BOL. A number of links to other Web sites were added to articles, demonstrating how BOL might serve not only as a source of reliable information and instruction in itself but also as an edited guide to the best of what the Web might come to offer.

In September the firewall was opened to those colleges and universities that had already subscribed to BOL. It was not, all in all, a difficult sell. Where the typical college library bought a single set of Britannica, stashed it in some out-of-the-way spot on the open shelves, and replaced it every five years with an updated printing, BOL was available instantly to every student and faculty member from his or her desktop and was kept as current as the editors, and their ATG colleagues, could make it. The information in it was more thoroughly indexed, more easily navigable, hence more accessible than that in the print set, and there was never any waiting for the volume one needed to be returned to the shelf.

The opportunity to demonstrate the power of (nearly) real-time updating had to await the development of new technical capabilities, notably the ability to edit, parse, WAIS-index, and insert a single article into the database. On September 6, 1995, Cal Ripken, Jr., of the Baltimore Orioles broke Lou Gehrig’s 56-year-old record for consecutive games played; two days later – the technical tools still being fairly crude – the article on Gehrig, which had stated that the record remained unbroken from 1939, was revised to acknowledge Ripken’s feat. A small step for an editor, a giant leap for electronic publishing.

Part II

From its first release in September 1994, Britannica Online was a great success with its first intended audience: colleges, universities, and libraries. By word of mouth, assisted by its beta- tester partners, and through the efforts of a tiny sales force, BOL secured a remarkable market share over the next two or three years. Some hundreds of institutions in the United States signed up, as did a number of overseas institutions who took the initiative themselves in making contact. A year later, in the fall of 1995, BOL was made available to individual subscribers as well, but BOL’s penetration of the consumer market never matched the company’s hopes. One chief reason, no doubt, was that at the institutional level no other encyclopedia could hope to match Britannica’s reputation or performance; while for many consumers, looking for homework assistance for younger students, there were credible competitors, especially those that were supplied freely with that newest of aspirational goods, the home PC.

At the time of its initial release, BOL was not considered by senior management to be the future of the company. From the home office perspective, the release of BIRS had shown the way to produce a consumer CD-ROM version of Britannica that the sales force could accept, namely one priced at the same level as the print set. Though it seems in retrospect nearly incredible, buyers were found for BCD 1.0 at $1500. One wonders how those few feel now about the purchase, or even how they felt six months later. A standard price-stratification program followed, with successive cuts in price down to a couple hundred dollars, below which it was feared that the sales force would begin to rebel. The disks were available only through the sales force, but as the price of the CD fell so, too, did the commissions, and while no one was certain where the floor was, there was no doubt that it existed. Suggestions for retail distribution of the CD were met with blank stares or worse.

With senior management’s orientation being defined by the direct-sales orthodoxy, the excitement that was felt over BOL was confined largely to the ATG staff, to the Chicago technical group, to many of the editors, and to a few others. The institutional market for the Encyclopædia Britannica had always been very small, little more than an afterthought in sales and marketing planning. BOL looked like producing more money than the print set had in that market, but not enough to make the next company president.

As a result of this rather dismissive attitude towards the project – which in any case was tolerated only insofar as it did not impede the production of BIRS and BCD 1.0 – and of the physical distance of ATG from Chicago, the ATG team had enjoyed a good deal of freedom, which turned out to be freedom to work on new technologies. A “project manager” for BOL was, in fact, appointed in Chicago, but he seldom visited La Jolla and delayed adopting email until early 1994, by which time it was too late to discover that he had little idea of what was evolving on the Coast.

What is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the ATG period is that the group did not find itself, in September 1994, with nothing to do. The launch of BOL on a paying basis was, on the contrary, just the opening they had been looking for. Alongside and in conjunction with the development of BOL they had been working on complementary ideas, ideas for enhancements and extensions that, they believed, would carry BOL and perhaps the company into the 21st century. There were three principal such ideas: Bibliolinks, Mortimer, and Gateway Britannica. They shared a vital premise: that the attributes of the Britannica – breadth and depth of scholarship, comprehensiveness, accuracy – held the potential to make BOL the center of the serious part of the World Wide Web.

Bibliolinks

The idea for Bibliolinks was a natural and seemingly simple enhancement. If the Britannica was a summary statement of human knowledge, then each article was similarly a summary of knowledge about that particular subject. All major articles and several thousand of the shorter ones supplied bibliographic references for further reading as an aid to the user who desired to go beyond the summary. Bibliographies ranged in length from a single work to multipage, highly structured surveys of whole fields of study. In addition, there were numerous references to published works in the running text of articles.

The project was carried out by Belew and Steier, beginning in the fall of 1993. The first step was to develop a software program to recognize the bibliographic citations in the text or bibliographies of articles, to separate the citations composing each bibliography, and to decompose each citation into the various types of information used to identify a particular item: title, author, publication date, and so on. This effort leaned heavily, of course, on the consistency of style used in the encyclopedia. Another program then compared these citations to records in Roger, the electronic card catalog of the library at UCSD. Where matches could be made with a predetermined level of probability, the text of the citation in the article was then tagged as a hyperlink pointing directly to the corresponding “card” in Roger.

In its beta state (not formally released to the UCSD campus until the fall of 1995), Bibliolinks was able to find and create links to Roger for upwards of 70% of the recognized bibliographic citations in BOL, a total of more than 200,000 links, with about 95% accuracy.

A BOL user, reading a Britannica article and coming to a reference to some published work or to the article’s bibliography, could see at a glance which items could be found in the UCSD library system. Clicking on the entry would bring up the Roger record, which would tell the user the call number of the physical item, which library held it, and whether it was currently available or checked out. This facility alone would have made Bibliolinks an important development. As the librarians were quick to recognize, however, there was another and potentially even more valuable application: Bibliolinks could serve as a natural language “front-end,” or search tool, for the library’s collection.

Where other online search tools were capable of searching on author’s name, title, or some relatively narrow set of search terms, Bibliolinks offered the same sophisticated search capability as BOL. Moreover, for the non-initiate, such as undergraduates, and for any searcher looking outside his or her field of expertise, the BOL-Bibliolinks tool provided not simply a list of relevant library holdings but an authoritative guide to further reading.

A major side benefit of the Bibliolinks project was that it forced the editorial group to undertake a project to review and update bibliographies that had not had adequate attention and to add still more to the encyclopedia. Unfortunately, except for that effort, the project came to naught. It underwent a series of postponements and suffered from the frequent changes of priority that handcuffed all the extension projects.

Mortimer

Early in 1993 Clarke and Bartell began a series of experiments in automatic text classification. Clarke brought to the work an understanding of the nature of classification and experience in automated cluster analysis, Bartell his knowledge of the application of neural networks to the problem of information retrieval. Still fondly recalled are Clarke’s first sketches of a graphical search interface, in which a few circles represented broad topics, within which would be represented individual “hits” (documents in the data being searched that were found to satisfy in significant degree the criteria for the various topics); the different diameters of the circles were proportional to the number of hits falling within each, or, as it was termed at the time, their “pregnancy.”

In building his experimental software, Bartell employed a mathematical technique called multidimensional scaling. Very roughly, groups of text documents were analyzed statistically to find associations among the lexical elements (words and phrases) of which they were composed. While particular terms might be characteristic of certain subjects, such terms are too few and infrequent to serve as reliable indicators for each of a large set of diverse documents. The tendency of clusters of terms to occur together in certain patterns, however, is much more diagnostic of subject matter, and it was these patterns that Bartell’s program was intended to detect.

Meanwhile, Clarke discovered the Propaedia. This volume of the Encyclopædia Britannica consisted chiefly of an elaborate “Outline of Knowledge.” The outline provided precisely what was needed in order to construct a tool that would not only cluster but classify documents, namely a logical and thorough taxonomy of topics. As part of his study of the Propaedia, Clarke got in touch directly with the Editorial group in Chicago, from whom he learned that each of the 64,000-odd articles in the Micropaedia portion of the encyclopedia had been classified against the Propaedia outline. One or more tags denoting the classification(s) of each article were part of each article’s text file in PSEdit.

A training set of about 45,000 tagged Micropaedia documents (some 70% of the whole) was selected and submitted to analysis. The neural network in effect “learned” how to recognize the semantic characteristics of articles in various categories. The first test of the software’s efficacy as a classifier was then to submit articles from the remaining 30%, without their Propaedia tags, and compare the software’s suggested classification with the editors’. Accuracy at the top level of classification – the ten principal parts of the Propaedia – was about 96%; it decayed progressively at successively deeper layers, falling to about 75% at the fourth level. In subsequent tests and demonstrations, the software’s output was generally held to three levels.

The next and far more demanding test was to submit text documents from other sources to the classifier. In the course of many months of development, sample data were obtained from the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and the yet-unpublished new edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Results varied with source but were uniformly good, sometimes excellent. The Grove articles, written in a style similar to that of Britannica, were classified with great accuracy. Articles from the New York Times varied in style and vocabulary; news articles were handled very well, while some feature columns proved hard to place in topic space. Editorial inspection of some of these showed that they tended to be musings about this and that, with no consistent or firmly stated subject; the classifier, interestingly, tended to place these in the category Literature.

The system was dubbed “Mortimer” by Kester, in honor of the originator of the Propaedia. As essential element of Mortimer was a method for displaying the results of the calculations performed by the software. In essence, for each analyzed document, a probability score was calculated for each possible topic, in this case 176 topics (the number of third-level rubrics in the Propaedia). These scores constituted a vector in a 176-dimensional space. That vector, and those of all other documents under analysis, had then to be projected onto the two-dimensional space of the computer screen. Distortion of one sort or another was inescapable, and there was no one correct answer; and, indeed, a lively debate over how to effect the visualization persisted for some months. The actual user interface adopted for demonstrations within Britannica and to outside parties, designed by John Dimm, showed the topic areas as large, irregular-colored regions. (The shape, size, and relative positions of these regions had previously been calculated in a similar fashion from the semantic statistics for all training documents in each classification.) Clicking on one of these areas would bring it to the foreground and reveal the next lower level of classification. By this means the user was able, in effect, to navigate down through the outline.

In March 1995 Bartell and Clarke filed a patent application for Mortimer; their patent for “Method and System for two-dimensional visualization of an information taxonomy and of text documents based on topical content of the documents” was granted in April 1997.

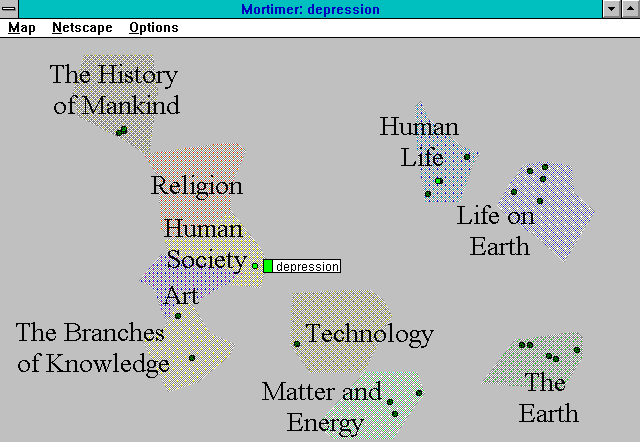

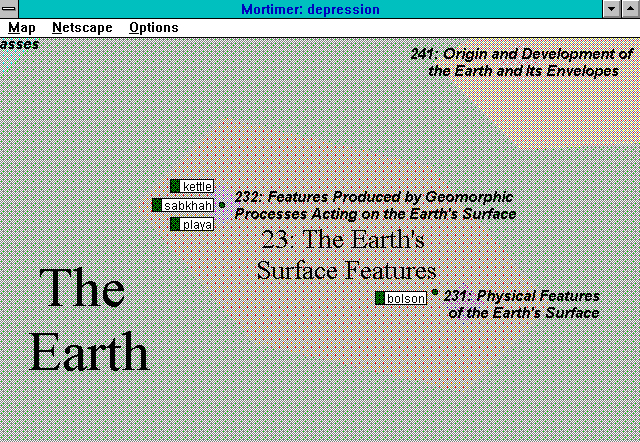

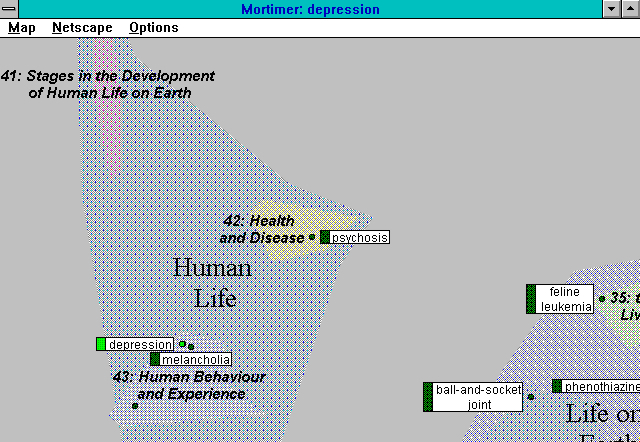

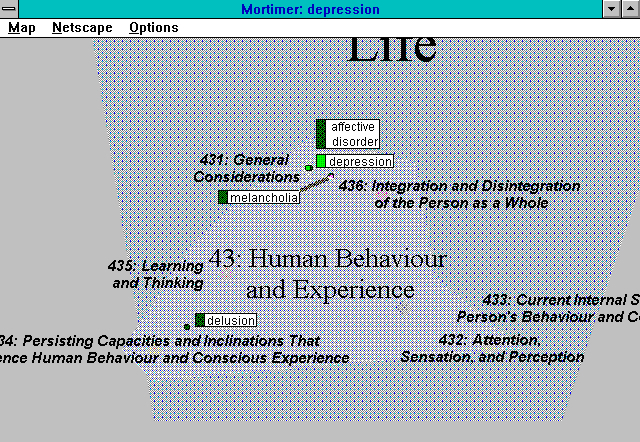

When Mortimer was given a search query, it would determine which documents in the set were relevant, assign a topic value to each, and place dots – indicators of “hits” – in the topic map. This ability was especially impressive when the query term was polysemous, i.e., might have any of several quite different meanings. Kester’s favorite term for demonstrating the power of Mortimer was “depression,” which might refer to economics, psychology, geology, or other matters. Here is the top level of Mortimer’s display of articles in Britannica relevant to the query term “depression.” The green dots indicate Britannica articles. The one judged most relevant, because its title matches the query term, has its title shown as well. If the user decided that the sense of “depression” in which he was interested lay in the area of Human Life, he could click on that area to produce a second topic map at the next level down; another click would bring the view down to the third level. Note that article titles are revealed as part of this navigation downward. Alternatively, had the area of interest been geological depression, the user might have clicked down from The Earth to this third level display.

This ability to detect and distinguish different senses of search terms is called “disambiguation.” No ordinary search engine could do this; no ordinary search engine can do it today. More remarkable still, Mortimer could run over several distinct databases of text documents simultaneously. Hits from different sources appeared as differently colored dots on the map. (Unfortunately, no screen shot of this is available.) It was this aspect of the tool that underlay the third of the imagined extensions of Britannica Online, the notion of Gateway Britannica.

Gateway Britannica

This concluding section of the history of the making of Britannica Online is more in the nature of a postscript, in that it looks at an idea that never got onto the ground, to say nothing of off it. It was an alluring vision that, from 1993 to 1995 or perhaps 1996, provided the core BOL team with a direction and much of its impetus.

From their first acquaintance with the Internet and especially with the World Wide Web, it became clear to the editors of the Britannica that they stood at the brink of a paradigm shift. (That overworked phrase is used here with no apology and no irony.) The printed and bound Britannica had customarily been imagined in the context of the individual at home, where the encyclopedia – however used – typically dominated physically the bookcase, even the room in which it was lodged. The editors had now to imagine the encyclopedia, as it were, shelved somewhere within the Library of Congress. The electronic version, existing for the user only as momentary tracings on the computer screen, might well become merely one of countless databases available in a vast and uncharted ocean of digital information. The ATG group, from their quite different perspective, and perhaps a bit earlier, grasped exactly the same point. The motive for Gateway was their shared determination to position Britannica, not as one resource among myriads, but as an entry point of choice for all serious knowledge seekers on the Web. (One of Kester’s internal presentations to senior management opened with an animated sequence in which angels tugged open a pair of ornate gates, to the accompaniment of a bit of Holst’s The Planets.)

Mortimer, clearly, was a key element in the plan. Mortimer offered the promise of systematic topical and query-driven access to a body of information beyond and far more extensive than the encyclopedia itself. The encyclopedia would serve a two-fold purpose: Its content would provide basic information about topics of interest to Gateway users, while its structure would provide a means of organizing and indexing the Web at large (or that portion of the Web given over to the kinds of knowledge with which the encyclopedia was concerned). Bibliolinks would perform a parallel function with respect to physical libraries.

Using demonstrations of Mortimer to broach the subject, Kester and others held exploratory meetings with representatives of the New York Times, the McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, the Grove Dictionary, among others, in an effort to understand how such diverse operations might cooperate in a Gateway project. Interest was high enough that several publishers furnished test data, as noted above. Kester worked up a detailed business plan.

The Gateway idea came to naught. In part the failure was owing to Britannica’s financial difficulties. Money for ambitious projects was, of course, hard to come by, but senior managers, feeling perhaps that they could not afford a single misstep, were unable to fix upon any strategy at all. Following the sale of the company early in 1995, the new ownership was overwhelmed by immediate problems. When a strategy for the company at last emerged, it lay in quite a different direction from the Gateway vision. Key members began leaving ATG, culminating in Kester’s departure in 1999. The La Jolla office, reduced at the end to engineering annual releases of the Britannica CD, closed in 2001.

Britannica’s Advance Technology Staff in La Jolla, California

Standing Left to Right: Lisa Carlson (Merriam Webster staff), Lisa Braucher Bosco, Harold Kester, John McInerney,

Seated: Brian Bartel, Chris Cole, Rik Belew, Amy Steier, Robert McHenry (then the Editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica), John Dimm, Bob Clark [c. 1995]