1967 Report of Cyrus Vance Concerning the Detroit Riots

1967 Federal troops during the Detroit riots

The Vance Report had concluded that the use of the Army to help control antiwar demonstrations and racial disturbances wasn’t an isolated, one-off mission, and the requirement wasn’t going away any time soon.

An abstract of the Report’s lessons learned reads:

Based on the experiences in Detroit, where rioting and lawlessness were intense, it appears that rumors are rampant and tend to grow as exhaustion sets in at the time of rioting. Thus, authoritative sources of information must be identified quickly and maintained. Regular formal contact with the press should be augmented by frequent background briefings for community leaders. To be able to make sound decisions, particularly in the initial phases of riots, a method of identifying the volume of riot-connected activity, the trends in such activity, the critical areas, and the deviations from normal patterns must be established. Because the Detroit disorders developed a typical pattern (violence rising then falling off), it is important to assemble and analyze data with respect to activity patterns. Fatigue factors need more analysis, and the qualifications and performance of all Army and Air National Guard should be reviewed to ensure that officers are qualified (National Guard troops in Detroit were below par in appearance, behavior, and discipline, at least initially). The guard should recruit more blacks (most of the Detroit rioters were black), and cooperation among the military, the police, and firefighting personnel needs to be enhanced. Instructions regarding rules of engagement and degree of force during civil disturbances require clarification and change to provide more latitude and flexibility. Illumination must be provided for all areas in which rioting is occurring, and the use of tear gas should be considered. Coordination at the Federal level to handle riots is emphasized. Appendixes include a chronology of major riots, memos, a Detroit police incident summary, police maps of Detroit, and related material.

Secretary Vance’s report came out in early 1968, just before race riots had exploded in Black neighborhoods of 130 cities after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4. Many states called up their National Guard troops to join police in bringing the rioting and looting under control. Simultaneously Regular Army troops had to be flown or trucked into Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Chicago from various Army bases. In all cases, they had to back up overwhelmed police and National Guard security forces. In the middle of the Vietnam War, this was not a mission for which the Army was either structured or prepared for. Two months later, the sense of mayhem in the country increased further when Presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles.

I was familiar with this new problem for the Army, since right before I enlisted, I had watched Chicago’s west side erupt in flames from my Loop office window, and later directly witnessed some of the rioting firsthand with my brother, Dick, who worked for the City’s Human Relations Commission. I also monitored bail and other court proceedings involving rioters at the Criminal Courts building at 26th Street and California Avenue.

In this period, Regular Army troops were bivouacked near the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago’s Jackson Park. The next month I was in the Army, and six months after that, I was again engaged with civil disturbances.

During the summer of 1968, Chicago remained in turmoil. Though Regular Army troops had left and returned to their barracks, violent anti-war demonstrations continued to wreak havoc on the city. Rampaging groups of demonstrators before the Democratic National Convention that August brought out the Chicago police in full force as well as the Illinois National Guard.

My brother Dick remained in the middle of this activity. His Report to the Director of the Chicago Human Relations Commission provided a detailed account of the anti-war demonstrations and violence he witnessed between August 24 and 28, 1968.

1977 Richard Gwinn Bowe

The Report gives a street-level view of the disturbances in both Lincoln and Grant Parks. The final confrontation between the demonstrators and police and National Guard in front of the Hilton Hotel took place during the Democratic Convention’s proceedings and provided a violent backdrop to its nomination of Hubert Humphrey to run against President Richard Nixon that fall.

In 1964, there had been race-related riots in Harlem and Philadelphia. In 1965, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles had seen a major race-related riot. Chicago, Cleveland, and San Francisco saw riots the next year. Then in 1967’s “Long Hot Summer,” a total of 163 cities were enflamed, including Atlanta, Boston, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Detroit, Milwaukee, Newark, New York, and Portland. Following Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, President Johnson dispatched Regular Army troops to Baltimore, Washington, and Chicago to supplement overwhelmed police and National Guard.

In the aftermath of these troop deployments, President Johnson created the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence.

With the nationally televised violence directly in the political realm later that year at the Democratic Convention, the Commission had delegated to Daniel Walker, later Illinois governor, the job of undertaking a study of the violence surrounding the Convention.

The Walker Report was formally titled Rights in Conflict: The Violent Confrontation of Demonstrators and Police in the Parks and Streets of Chicago During the Week of the Democratic National Convention of 1968.

It found there had been a “police riot” in addition to violence on the part of more than 10,000 anti-war demonstrators.

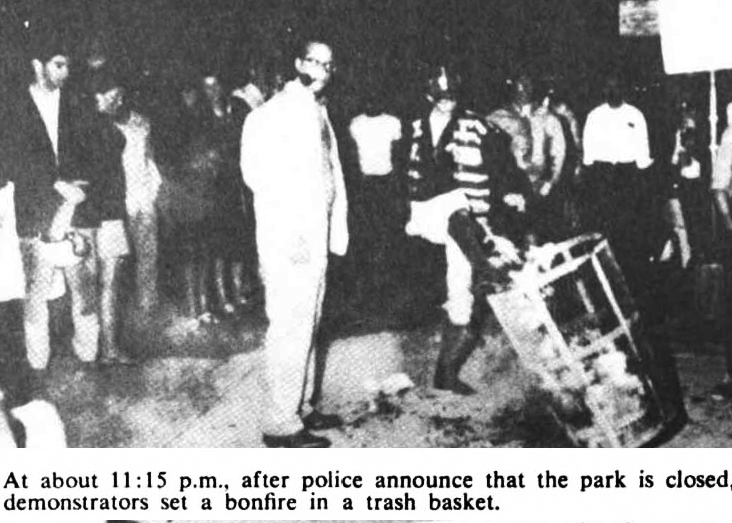

Richard Bowe with pipe by trash basket

In The Walker Report, you will find a picture taken by a Time Magazine photographer of my brother, Dick, about to remove a burning trash basket blocking traffic in the middle of La Salle Drive at the south end of Lincoln Park.

If not for Dick’s ever-present pipe sticking out of his mouth, I might not have recognized him or taken him to be one of the demonstrators, rather than an observer from Chicago’s Commission on Human Relations.