The Secretary of the Army’s Special Task Force on Military Surveillance

1974 Christopher Pyle at the US Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights Hearing on Military Surveillance

Pyle’s article prompted inquiries to Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor from various members of Congress, including Sen. Sam Ervin, the North Carolina Democrat who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights.

The responsibility fell to the Army’s Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Gen. Joseph McChristian, to gather the necessary information internally for the Secretary to respond to the detailed questions being raised. McChristian in turn asked the head of his OACSI’s Directorate of Counterintelligence, Col. John Downie, to take on the task. Since CIAD was under the head of the Directorate of Counterintelligence, I had recently begun to work more closely with Downie than I had up to that point. I had come to like and respect him enormously and thought him a strong and principled leader.

Five years later, following his retirement, Downie was interviewed about this period at his home in Easton, Pennsylvania, by Loch K. Johnson. At the time Johnson was a Congressional investigator for the U.S. Senate Committee popularly known as the Church Committee, named such after its chairman, Sen. Frank Church of Idaho.

Johnson was looking into the origins of the so-called Huston Plan to ramp up domestic intelligence operations by the FBI and the military. It had been approved for implementation by President Nixon and then immediately curtailed by the Nixon White House.

In Johnson’s later 1989 book, America’s Secret Power, The CIA in a Democratic Society, Johnson explains that the Huston Plan was a crash effort to analyze how to expand domestic surveillance of internal intelligence targets quickly and substantially, particularly student radicals and their foreign connections.

Johnson writes that Col. Downie represented the Army at critical meetings in June 1970 to review the Plan. The group met at CIA headquarters and was attended by FBI, DOJ, NSA, and other representatives of the pertinent civilian and military agencies who were tasked to respond to the White House directive.

America’s Secret Power by Loch Johnson

While Johnson says that there was some enthusiasm for expanded efforts by representatives of the CIA, NSA, and most of the FBI representatives, he quotes Col. Downie as making clear that the Army wanted “to keep the hell out” of any such effort.

Contemporaneously with this, Col. Downie had tasked me to review the Army’s legal authorities for domestic engagement. I had reviewed with him the particulars of the Posse Comitatus Act, originally passed in 1878. This one-sentence law today reads:

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

Since its passage, the law and its offspring have been bulwarks against permitting the military to meddle in what are essentially civilian law enforcement matters.

When Col. Downie had asked me to undertake this research, he had made no specific mention per se that the Huston Plan was afoot. However, it was clear something big was up and being treated as an emergency. I also was aware Col. Downie indeed had firm ideas on keeping the Army out of this kind of engagement. Furthermore, with the Army at the time facing Senate hearings on allegations of the military surveillance of civilians, the last thing it needed was a thoughtless push to apply its resources into what was by tradition and law a purely civilian responsibility.

With the first round of military surveillance hearings in the offing in early 1971, my immediate work area of the AOC was rearranged. My desk was in the same place, but it had turned 90 degrees. This struck me as a symbolic reflection of the Army’s own change of course in the intelligence gathering at this time. I was also given an elaborate new title that I didn’t know I had at the time: Staff Researcher and Allegations Analyst, Allegations Branch, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, and Department of the Army Special Task Force.

Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor

What Under Secretary of the Army McGiffert had tried and failed to do in 1969, now got done. Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor told Gen. Westmoreland on March 6, 1970, to make sure no computerized data banks on civilians should be instituted anywhere in the Army without the approval of both the Secretary of the Army and the Chief of Staff. The new Under Secretary of the Army, Thaddeus R. Beal, wrote Sen. Ervin on March 20 that the spot reports on violence created by the Army would be kept for only 60 days. Later directives flatly banned the use of computers to store proscribed information on civilians.

Pyle wrote a second article with additional allegations in a July 1970 Washington Monthly article on military surveillance, and I went back to work with my fact gathering. Then at the end of the 1970s, a whole new batch of allegations of Army spying on civilians appeared and received wide media attention. John M. O’Brien, a former Staff Sergeant with the Military Intelligence Group in Chicago, told Sen. Ervin that prominent elected federal and state officials had been spied on by the Army, including Sen. Adlai Stevenson III, Rep. Abner Mikva, and former Illinois Governor Otto Kerner.

Fred Buzhardt, General Counsel of the Department of Defense

In the wake of all these allegations, the first Senate hearings on military surveillance took place on March 2, 1971. Fred Buzhardt, General Counsel of the Department of Defense, must have thought the hearings went well for the Army, as he sent a letter to the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Westmoreland, complimenting him on the materials used to prepare for the hearings.

Westmoreland in turn complimented Gen. Joseph McChristian, his Chief of Staff for Intelligence. McChristian, who had also been Westmoreland’s intelligence chief when Westmoreland was commander of the forces in Vietnam earlier, in turn thanked the head of his Counterintelligence Division, Col. Downie. And Col. Downie kept the ball rolling by sending me an attaboy to round things out.

It meant something to me at the time, because I had come to know Col. Downie well in my time at the Pentagon, and I admired him as a decent, straightforward officer who had devoted his life in the honorable service of his country. When I first began working with Col. Downie at the Pentagon, I had been introduced to the heart and institutional memory of the Counterintelligence Division of OACSI. I don’t remember her last name, but Millie had served as the CD’s indispensable secretary for several decades.

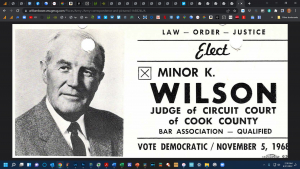

Col Minor K. Wilson (U.S. Army Ret.)

When I learned about her tenure, I asked her if she’d ever run across a now-retired counterintelligence officer in Chicago that was a family friend, Col. Minor K. Wilson.

Did she know him! She nearly fell off her chair that I knew him too. When she was a young secretary new in the Directorate, Col. Wilson was ending his Army career in the same job Col. Downie now held. Small world indeed, as after my father’s death in 1965, Col. Wilson, a friend of my father’s brother Augustine Bowe, sat at my father’s desk for a time at the family law firm, Bowe & Bowe, at 7 South Dearborn Street in Chicago. Soon joining my uncle as a judge, Wilson gave up my father’s chair for a new seat on the bench.