1967 The Indiana Dunes

1968 At O’Hare Airport on leave from Basic Combat Training

1968 At the Ross Hardies law firm

With the draft and these military service options off the table for one reason or another, I graduated from law school in June 1967 at the age of 25 and started working at a downtown Chicago law firm. Among other clients, the firm represented Northwestern Railway and various gas and electric utilities. The mid-sized Ross, Hardies, O’Keefe, Babcock, McDugald & Parsons had its offices in a National Register of Historic Places classic. The building was architect Daniel Burnham’s 21-story, 1911 Beaux-Arts building at 122 South Michigan Avenue, just across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago.

During law school, I had bypassed living in Hyde Park near the University of Chicago to help my mother care for my father in his declining health. He had died halfway through my time in law school, so after graduation I left my widowed mother and moved into the Hyde Park apartment of my college and law school friend Bob Nichols. I traveled to my new lawyering job on the Illinois Central commuter train from the 56th Street Station in Hyde Park to the Van Buren Street Station by the Loop. That left me a short walk to the Ross, Hardies office.

The main military option that still seemed open to me, in this period, other than the draft, was to enlist in the military in a way that might improve my odds of living long enough to get discharged. If I didn’t enlist in the military in the ensuing year, and got drafted as a result, it would most likely mean service in the Army’s infantry, and I’d be out of the military in only two years. A big negative of the draft was that I’d be out even earlier if I were killed in Vietnam.

Of course, why didn’t I think of it sooner?! Forget joining the military the way my father and Dick did. Instead of the Army or National Guard, join the Navy or Air Force. Or better yet, join the Army, Navy, or Air Force as a lawyer. I was pretty sure those folks weren’t getting killed much in Vietnam. With a law degree and admission to the Illinois bar in hand, I could enter the Judge Advocate General branches as an officer and gain directly pertinent experience for my chosen profession.

The unappealing part of this choice for me was the time commitment. With demand high to stay out of the infantry, these slots typically required a minimum four-year commitment. The other problem I had with being a military lawyer was the great danger I saw of being bored.

The possibility of being assigned to spend several years of my life defending or prosecuting AWOLs, handling damage claims brought about by tanks taking too wide a turn, or otherwise spending my time on mind-numbing tasks, was completely abhorrent to me. My solution to this quandary, six weeks before I turned 26, was to enlist for three years in the Army Intelligence Branch on May 13, 1968.

Like all recruits, I was going off to Basic Training that day.

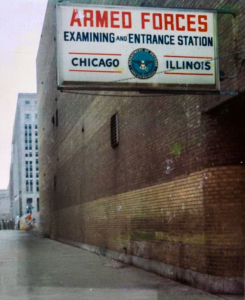

Army Entrance and Examining Station, 615 West Van Buren Street, Chicago, IL

Seriously hung over from a farewell party thrown by friends the night before, I was dropped off that morning at 6 a.m. at a large yellow brick building west of Chicago’s Loop. Later converted into a headquarters for Tyson’s Chicken, this was the same building where I had recently had the physical exam that found me qualified to enter the Army. That was literally my first exposure to Army life. I was required to strip off my clothes and walk naked single file with dozens of other men along a painted line that wove up, down and around two floors. Sprinkled along the painted line were way stations for you to pause at for various intrusive inspections of your body. To this day, I remember the impolite request barked at the most humiliating stop, “BEND OVER AND SPREAD ‘EM.” This experience gave me a better understanding of how those Tyson chickens must feel as they head down their own conveyer line of peril.

Bused to O’Hare International Airport, we were flown to St. Louis, and then bused from there to Fort Leonard Wood in central Missouri. I, and the other recruits I had been batched with, got off the buses and were ushered into a large room where we were seated in pews.

We were told that if any of us had any guns, knives, brass knuckles, or other weapons on our person, we were to take them out and leave them on our seats. Left unspoken was the, “Or else!” part. To this day I remember the continuous clanking of metal hitting wood that seemed to go on and on. I had no idea that some of the folks I was travelling with were well armed long before they were even issued a uniform.

The eight-week training regimen had the usual components: calisthenics, learning how to march, marching, the rifle range, the grenade range, and the low crawl under chicken wire with machine gun fire above.

In a large gymnasium filled with sand pits we were given pugil sticks for mano a mano battles. I think this was to teach us that as soldiers we needed to be a little more aggressive in our approach to life.

Large signs with slogans adorned the gym’s walls. One read, “Wars were never won with conscience or compassion.” I recall thinking at the time that while that may be true, it was also true that a little more conscience or compassion might help stop wars from starting in the first place.

Approaching the end of Basic Training we were sent out into the field for a week’s long bivouac exercise.

1968 At O’Hare Airport headed to Baltimore and Army Intelligence School

In a final reminder that Army life was going to be different than civilian life, my training company of 120 men were marching for what seemed like forever down a gravel road surrounded by pine trees on both sides.

These woods were most unusual in that nature hadn’t made this forest. The forest was a man-made, manufactured forest. All the trees were the same 20 feet in height, and all had been planted and cultivated in perfectly lined up rows.

As we marched along the road in single file (so as not to be bunched up and more vulnerable as a group to sniper fire), I noticed two signs, one above the other, on one of the trees. The top sign read, “Hunting Area 7.”

The sign beneath it read, “No Hunting.” It was at this point that it really sunk in that my life the next three years was going to be very, very different.