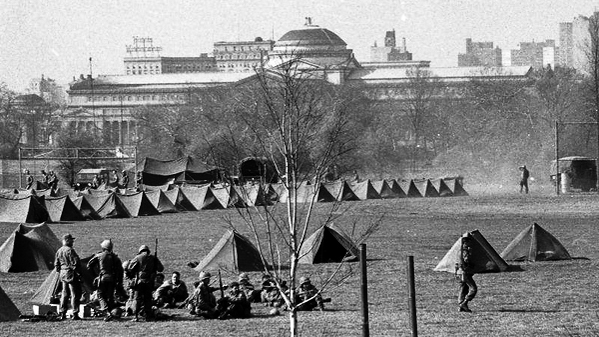

1969 Richard Nixon Counter-Inauguration Protest

I remember being on duty in the new AOC in January 1969 when President Richard Nixon was being sworn in. With the country on edge in the aftermath of the riotous Democratic Party convention in Chicago the preceding fall, the seat of the federal government was a constant target for antiwar demonstrators, and the frequency and size of their gatherings in Washington were increasing. The AOC was in a subbasement Pentagon space. Built as a duplex war room with ancillary offices, its entrance was guarded day and night and restricted to those with proper security clearances. On one side of the two-story war room atrium was a glassed-in command balcony where civilian and military decision makers sat. From this perch they could look down upon the military worker bees at their desks on the floor below, or they could look straight across the atrium at the wall opposite.

This wall was filled with several large projection screens showing maps and troop positions. Other screens could display any live television coverage of ongoing demonstrations.

In standard military fashion, operational briefings in the AOC began with a uniformed Air Force officer giving the weather report. Addressed always as Mr. Bowe, with no indication of rank, I would follow in civilian dress with the intelligence report. As you might expect, the most useful intelligence had to do with the expected size and likely activity of demonstrators. For this purpose, widely available, non-classified newspapers and other common publications were a primary source I used to build my estimates.

1957 Charles Van Doren on Twenty-One

The Air Force weather officer and I would precede the operations portion of an AOC briefing. All speakers would deliver their remarks from glass briefing booths on either end of the upper level of the AOC. The briefers were visible to the adjacent command balcony, and, because the pulpit-like booths jutted out a bit over the lower level, briefers were also visible to the joint service officers coordinating information on the lower level.

The only thing I had seen like this was the isolation booth Charles Van Doren was in when he answered questions on the rigged Twenty-One television quiz show in the late 1950s, and the bulletproof glass cage where Nazi Adolf Eichmann stood when he was on trial for war crimes in Israel in 1961. While the AOC was a state-of-the-art war room for 1968, later decades made it in retrospect look like a modest starter home compared with the McMansion war rooms that became all the rage.

I always thought Van Doren and I did better than Eichmann after we left our respective glass booths. Eichmann, of course, got the noose, but both Van Doren and I later in life worked on a Greek-language publishing project that Van Doren had initiated at Encyclopaedia Britannica. This was shortly before he retired and I arrived. Years later, when Van Doren came to Chicago in 2001 for his mentor Mortimer Adler’s funeral, I mentioned to him that I had inherited this last project of his.

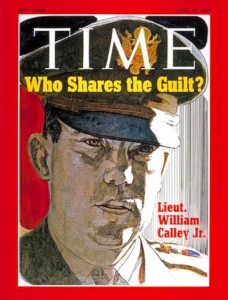

1969 Lt. William Calley, Jr.

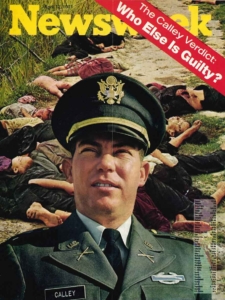

1971 Lt. William Calley, Jr.

The AOC could be a strange place at times. In December 1968, I saw accused mass murderer Lieutenant William “Rusty” Calley, Jr. in the AOC. I had my desk at the time in the AOC, and one day after lunch, as I came in past the security desk at the entrance and entered the complex, I happened to glance to my left into the anteroom. There, looking very much alone, sitting by himself at a small table, was Calley. I recognized him immediately. His time in Vietnam had landed him on the cover of both Time and Newsweek that week. With the tragic My Lai Massacre all over the press, he had been sequestered for interrogation by the Army in the safest out-of-the-way spot it could find for him, the AOC.

Hoffman Building, Alexandria, Virginia

CIAD Bailey’s Crossroads, VA Warehouse Office

Sometime in 1969, before I got my office in the AOC, CIAD had moved from our windowless quarters next to the Northern Virginia Community College’s automobile shop to more upscale quarters in the Hoffman Building office complex in Alexandria, Virginia. This building had plenty of light, was near the beltway, and was close to the Wilson Bridge over the Potomac. While I had a desk there for the duration, I was spending most of my time in either the AOC or another Pentagon office. Another space at the Pentagon that I rotated through daily was entered through a nondescript door on a busy corridor on one of the Pentagon’s outer rings. I was moving up in the world. Having started with an interview in OACSI’s lowly assignment office, I had moved up to a first-class basement duplex with the AOC. Now I had been promoted part of the day to an above-ground cubby hole in one of the prestigious outer rings.

In this easily overlooked spot in a highly trafficked hall, one indistinctive door led to a small reception area. I regularly had on a neck chain my Army dog tags, my Pentagon ID, my Hoffman Building ID, my AOC ID, and an ID for this area. Behind the door’s guard was an inner sanctum of windowless offices. This space was where highly compartmentalized, secret intelligence information collected by various foreign and domestic intelligence agencies could be viewed. It was interesting stuff to plough through daily, but rarely bore directly on my main job of preparing and delivering written and oral briefings on the likelihood of demonstrations or civil disturbances.