This series of recollections came about because when the pandemic hit in early 2020, I feared my increased irritability during the ensuing lockdown could be a telltale sign I was descending rapidly into curmudgeonhood. Thinking this would be unfair to the dogs, not to mention my wife, Cathy, I decided I needed a project to keep my head straight.

This series of recollections came about because when the pandemic hit in early 2020, I feared my increased irritability during the ensuing lockdown could be a telltale sign I was descending rapidly into curmudgeonhood. Thinking this would be unfair to the dogs, not to mention my wife, Cathy, I decided I needed a project to keep my head straight.

With help from YouTube videos and a tutor who knew more about building websites than I did, within a year I had built a genealogy-oriented website chock-full of my kin’s family trees. With no end to the pandemic’s lockdown in sight, my question became what to do next. That’s when I started thinking and writing about several of the strange periods I had lived through in the years since my graduation from law school in 1967. While the five stories in this collection that came to mind are very different from one another, together they all tend to reflect some of the larger historical drivers that define their periods.

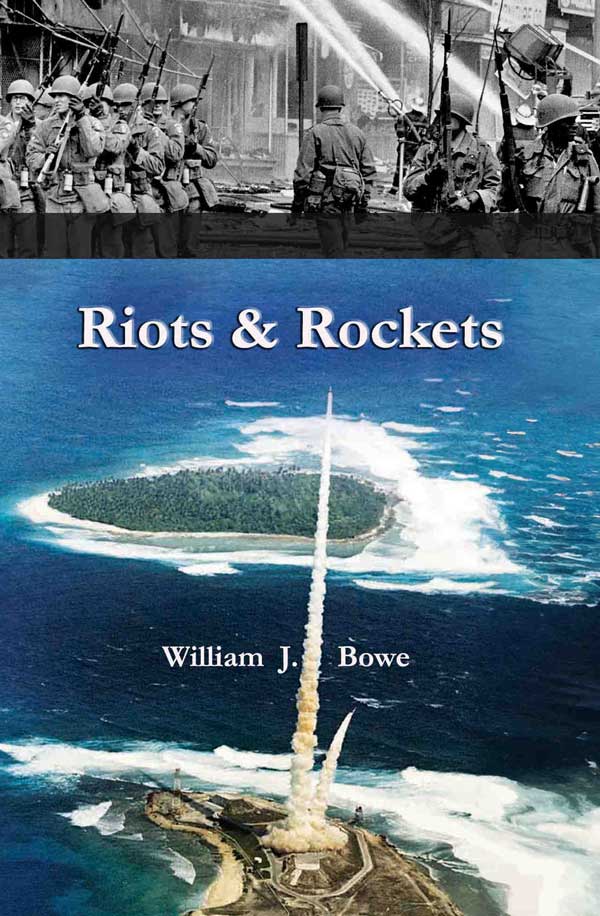

In the 1960s the country was torn apart by large scale racial violence, large scale anti-war protests, and emergence of the sown seeds of revolutionary violence. The title of this book, Riots & Rockets, is taken from the first story and comes from this era. My account of this period arose from my service in the U.S. Army as a counterintelligence agent in the Pentagon. There I was assigned to provide estimates of violence likely to involve the commitment of Regular Army troops in a domestic peacekeeping role. Beyond that role, I was separately tasked to analyze potential security deficiencies in the nation’s first anti-ballistic missile system. Between the two jobs, I had a ringside seat to the worst period of civil distress and violence the country had seen since the Civil War, and I also had a window through which to view how space began to evolve as its own distinct war theater.

Next, I turned to writing about a period when I worked as a lawyer for Rod MacArthur, the scion of billionaire John D. MacArthur. The senior MacArthur’s estate largely went to the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and part of my job was to advise his offspring in connection with his role as a director of what was then and now one of the country’s largest foundations. Although increasingly frustrated with his fellow directors, the younger MacArthur threw himself into creation of the Foundation’s Fellows Program, popularly known as the “genius grants.” Shortly after I went on to other things, MacArthur crossed his personal Rubicon and sued all his fellow directors for mismanagement and to liquidate his father’s Foundation. His lawsuits and his life both soon ended abruptly with his untimely death.

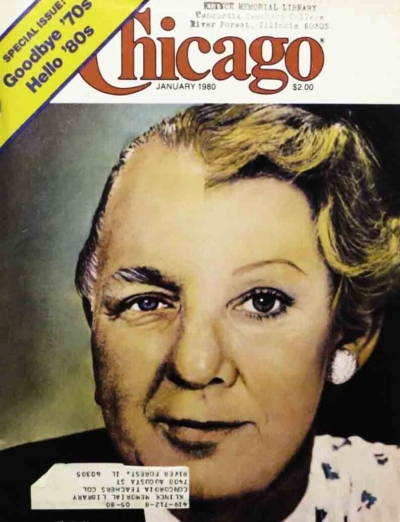

Being active in Chicago’s mayoral politics in the 1970s, I next wrote about that. This story encompassed the death of Richard J. Daley’s fabled political machine with the election of the city’s first woman mayor, Jane Byrne. It concludes with her defeat and the election of her successor, the city’s first African American mayor, Harold Washington.

The next logical tale for me to tell was the spectacular failure of one of the nation’s most important media companies. Throughout most of the twentieth century, United Press International was the major competitor of the dominant Associated Press newswire service. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, UPI began seeing reduced revenues as the number of its newspaper clients declined as advertising dollars shifted from newspapers to television. However, UPI’s descent into bankruptcy was not merely the result of this broad technology-driven event. Its demise had been hastened by the unfortunate sale of the company to two incompetent, self-aggrandizing twits who knew nothing about the business. If Silicon Valley startups are famous for the “fake it till you make it” syndrome, this pair were practitioners of the older “fake it till you break it” disorder.

The last period I chose to write about was the early part of Digital Age in the 1980s, when the personal computer came on the scene. In this period, print reference publisher Encyclopaedia Britannica, founded in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1768, became the unlikely patent holder covering a software navigation scheme that permitted children as well as adults to easily search media-rich content combining text, audio, video, graphics, and maps. Though the patent turned out to be monetarily worthless after decades of litigation, Britannica’s invention can still be seen as a fundamental milestone in the digital navigation experience that today we take for granted.

These five stories are for better or worse the accounts of a single witness. While putting the tales together in the style of a memoir serves to tie them together with a single thread, it also means these accounts of people and events are inevitably knitted to any factual errors or lapses in the author’s memories.

William J. Bowe

Northbrook, Illinois

January 15, 2024