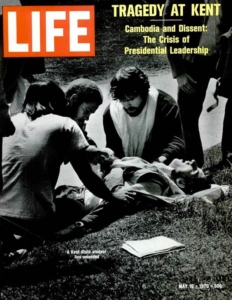

Four Dead in Ohio – National Guard troops at Kent State University

Student protestors on the Kent State campus

On April 20, 1970, Nixon announced that 115,500 American troops had left Vietnam and another 150,000 would depart by the end of 1971. To many it looked as if his Vietnamization strategy might be working. However, just 10 days later, on April 30, 1970, he announced that U.S. and South Vietnamese troops had entered Cambodia to attack the safe haven there that had been a refuge for North Vietnamese forces.

Many colleges and universities across the country were convulsed and promptly gave witness to both peaceful and violent demonstrations protesting the Cambodian expansion of the war. One such school was Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, some 30 miles southeast of Cleveland, with a campus of 20,000 students.

Campus ROTC building burned down by protestors

On the day after Nixon’s announcement of the Cambodian bombing, Friday, May 1, violence in the streets of downtown Kent resulted in the Governor calling up the National Guard for duty. The next night, Saturday, May 2, protesters set the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) building on fire. Elements of the Ohio National Guard arrived using tear gas and bayonets to clear the area.

The next day, Sunday, May 3, 1970, there were 1,200 Guardsmen on the Kent Campus to confront the student demonstrators. In the ensuing standoff, some of the Guardsmen fired their M-1 rifles into the crowd. When the shooting stopped, there were four dead students and nine wounded.

Life Magazine covers the shootings

My job every Monday at the time was to drive to the Pentagon in the early morning hours before dawn and read the FBI teletype and Army spot reports that had come in over the weekend. My focus was on incidents of violence that might engage, or had engaged, National Guard forces. This level of violence would always be a prerequisite of any later call for Regular Army troops. When I had gone through the traffic and made my assessment, my job was to go up from the basement location of the AOC to the Office of the Under Secretary of the Army and brief his military aide on what if anything was going on.

The Under Secretary was the civilian point person managing the Army’s civil disturbance mission, and he and his office wanted to keep close tabs on anything that might evolve into a crisis engaging Army troops.

In 1969, David McGiffert had served as Under Secretary and had learned enough to conclude that the Army had drifted into collecting some information domestically through its U.S. counterintelligence units it shouldn’t be collecting. He had further concluded that it could embarrass the Army if it continued unchecked. Though he was clearly on record in this regard, civilian leadership in the Nixon administration and the Department of Justice did not concur. As a result, various local Army counterintelligence units continued to funnel reports of demonstrations being planned or occurring that were not strictly necessary to carrying out the Regular Army’s limited civil disturbance mission. I had been correct in the technical assessment that I gave the Under Secretary’s aide that the Kent State student deaths and the other mayhem over the weekend would not lead to any engagement of the Regular Army. That was a no-brainer.

But I was about as wrong as you could get in my collateral observation that the outbursts would have a short life and that the campuses would settle down in the ensuing week.

1970 Anti-war March on Washington

The next week instead saw demonstrations of more than 150,000 in San Francisco and 100,000 in Washington, D.C. And on different colleges and universities, National Guards were deployed in 16 states on 21 campuses, 30 ROTC buildings were bombed or burned, and there were reportedly more than a million students participating in strikes on at least 883 campuses.