Johnston Atoll and the Origins of Space Warfare

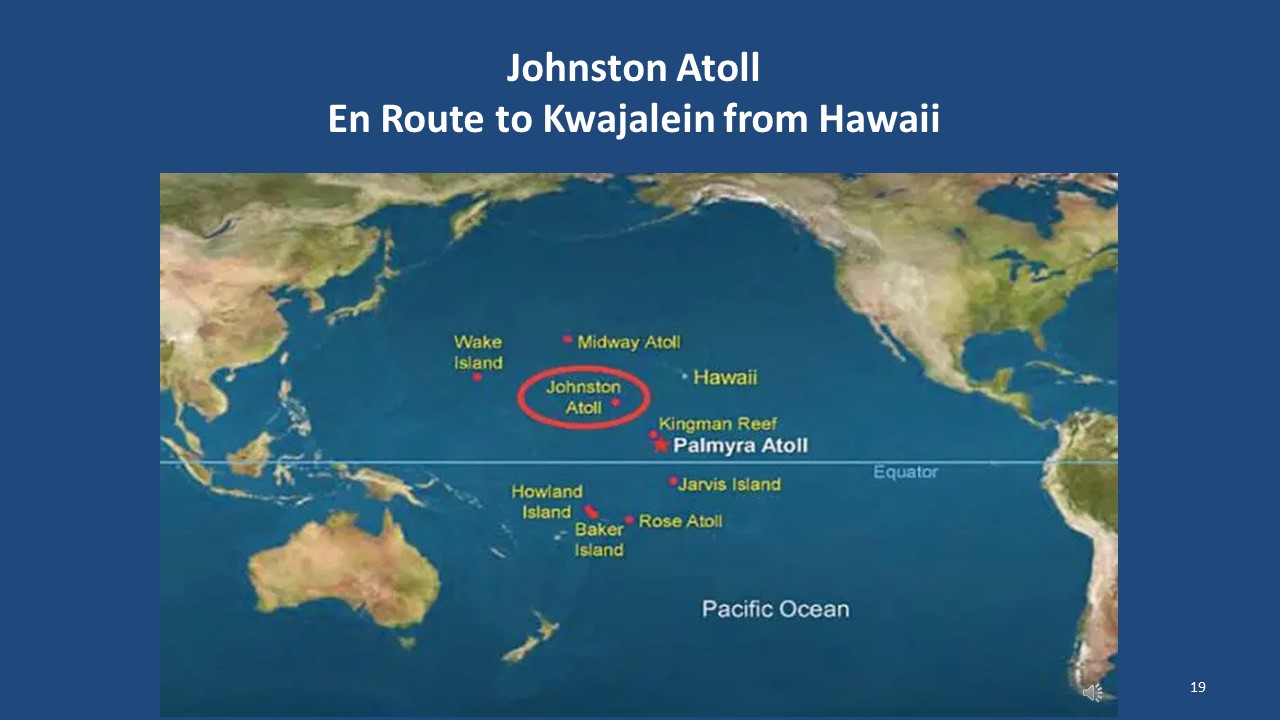

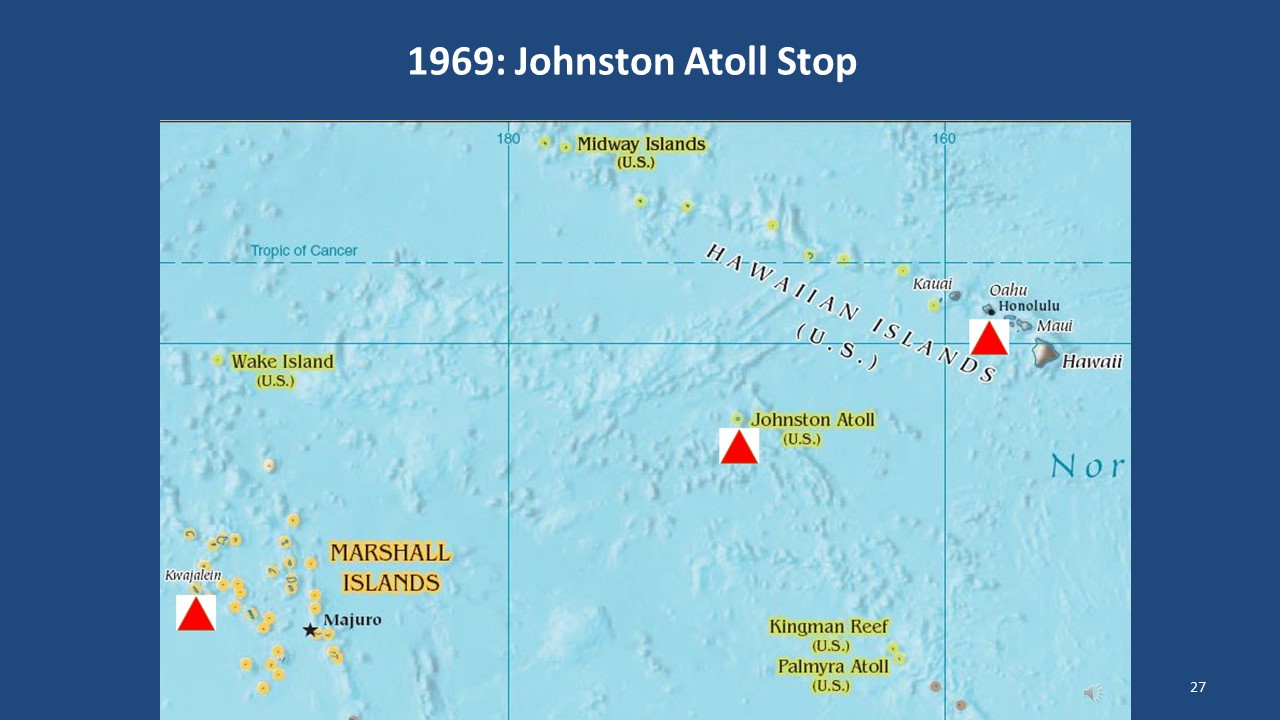

Kwajalein Atoll is about as far west of Hawaii as Los Angeles is its east

Northwest Airlines, with its distinctive fleet of red-tailed passenger jets, had a contract with the government to fly military personnel and civilian contractors with security clearances from Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu, Hawaii, west to Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. I knew how long the non-stop flight to Kwajalein was going to take, so I was surprised when we suddenly began descending well short of our destination. There was no engine malfunction, so why land in the middle of the Pacific if you didn’t have to? I had no desire to emulate Amelia Earhart, so I was increasingly nervous about what might be an unexpected descent into oblivion.

1970 Johnston Atoll

My anxiety was quickly relieved when the pilot came on the squawk box to say we should buckle up for landing to refuel at Johnston Atoll. The runway at Johnston seemed only about as long as the atoll itself, leaving no room for error on the pilot’s part. I stared out the airplane window in awe as we decelerated, finally rolled to a stop, and then taxied back to the other end of the runway to deplane.

Though my visit was short, Johnston Atoll ended up being one of the strangest places I have ever been to in my life. It’s a small, isolated, and currently uninhabited atoll in the vastness of the south-central Pacific, and it lacks natural access to any fresh water. Despite these impediments to human habitation, I later learned that Johnston Atoll had a long, if fitful, history of human habitation before my arrival in late August 1969. Indeed, there was a period when over 1,000 personnel, some accompanied by their families, lived on Johnston Atoll. These folks were working on extremely dangerous military projects in the highest level of secrecy.

1970 Johnston housing

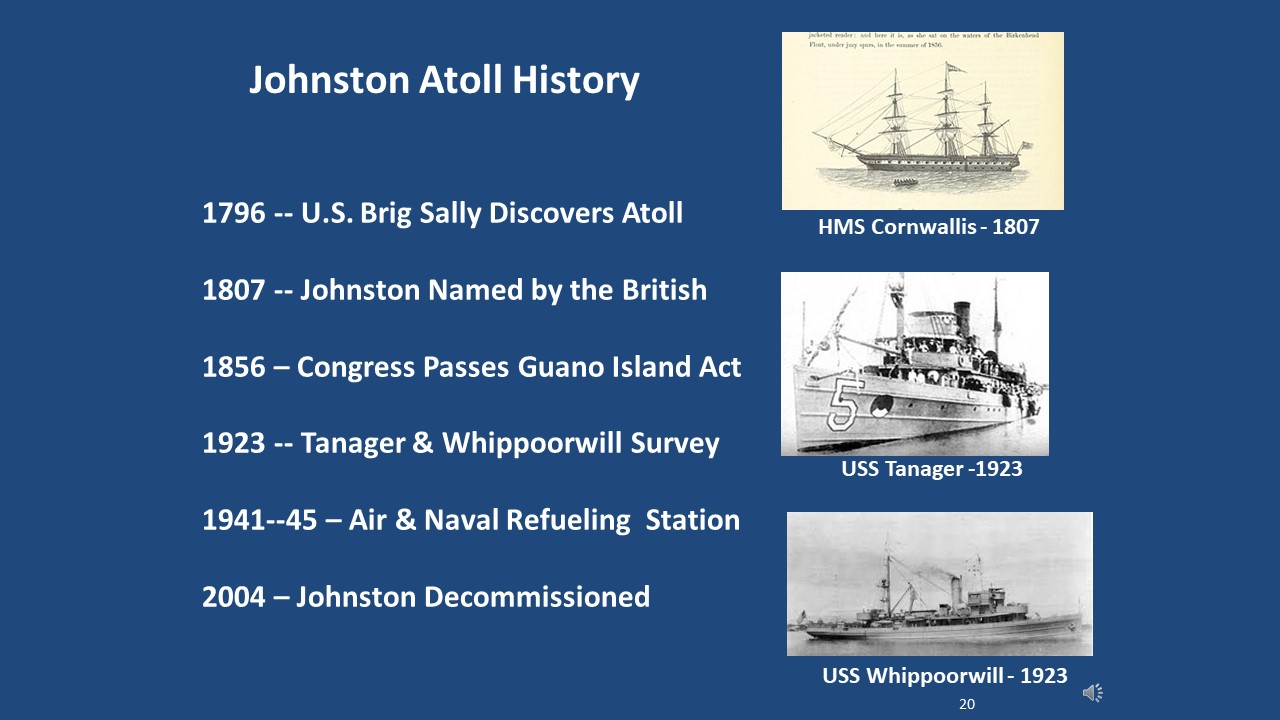

Johnston’s history started late. In 1796, the Boston-based brig “Sally” first discovered the atoll when it ran aground there while transiting the Pacific. The British ship HMS Cornwallis bumped into Johnston a few years later in 1807. Its Captain, one Charles Johnston, quickly and immodestly named the atoll after himself. Commercial development of the Atoll’s substantial guano deposits began after the U.S. Congress authorized this business in the mid-19th century.

USS Whippoorwill

In the 20th Century, when the guano enterprise was long gone, the U.S ships Tanager and Whippoorwill did scientific surveys in the 1920s.

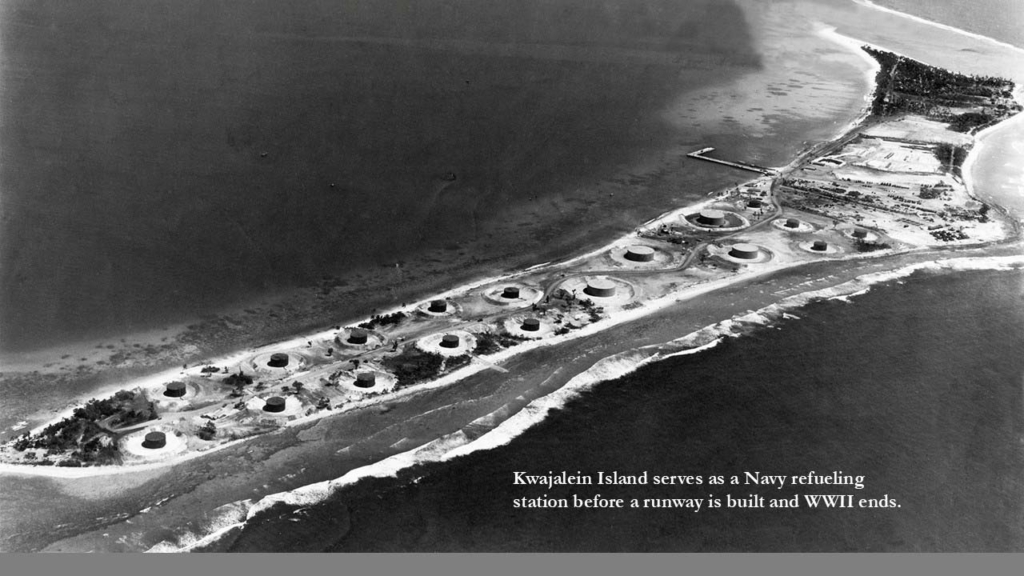

During World War II, Johnston served as a Navy and Army Air Force refueling depot. Then, during the Cold War, military requirements changed. This led to substantial dredging of the Atoll’s coral reef and shallows and the incremental expansion of the tiny Atoll’s land.

Beginning in the late 1950s, U.S. defense planners began to become worried that the Soviets might soon be able to launch satellites into orbit with nuclear bombs aboard that could be launched at will on ICBM installations in the US or, God forbid, on U.S. cities. This worry raised the concomitant question as to whether such orbiting satellites could be destroyed by detonating a nuclear warhead in their vicinity. To test this theory, in 1958 the first of a series of lower altitude nuclear tests began at Johnston Atoll. The purpose of the Project Fishbowl test in 1962 was to find out what happens when you detonate a nuclear weapon in the upper atmosphere.

In the anti-satellite tests at Johnston, modified Thor missiles with nuclear warheads atop were launched to see whether X-rays generated by detonation of their warheads would actually be capable of destroying hostile Soviet satellites.

Growth of Johnston Island

1945 WWII Navy Refueling Station

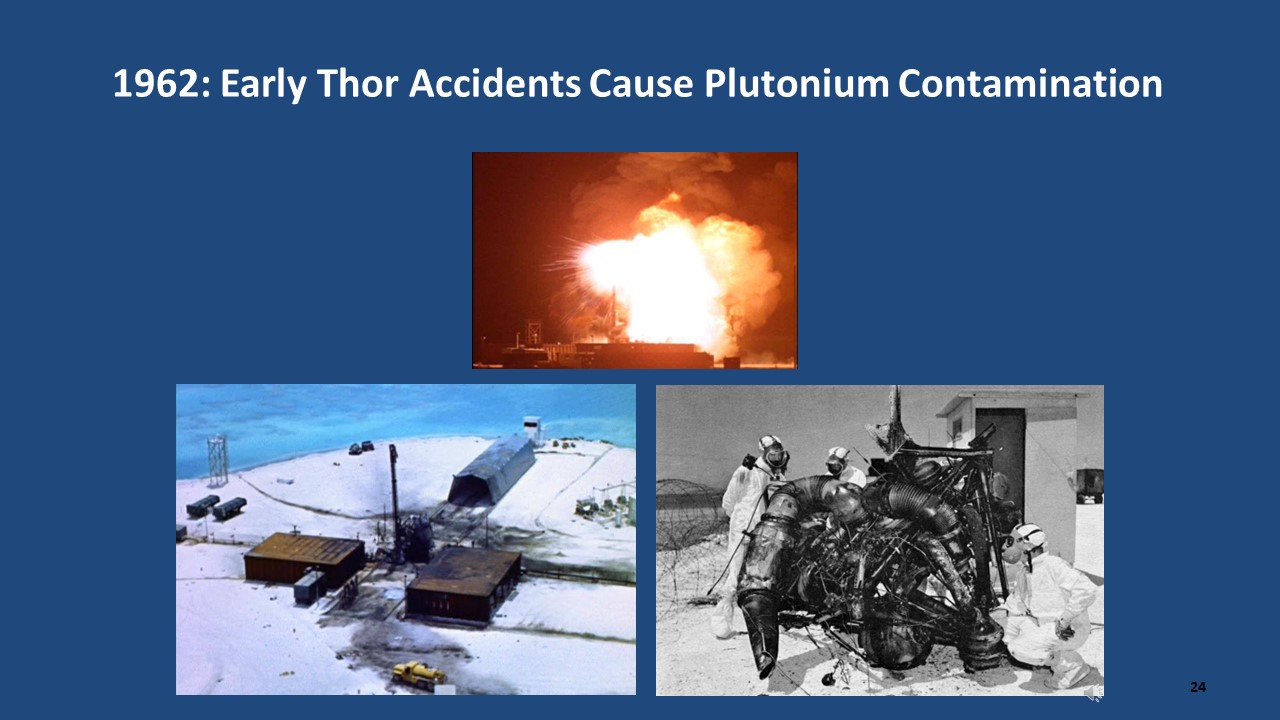

In one early test failure, a Thor missile blew up on its launch pad and spewed plutonium over the Atoll. This resulted in a complicated and lengthy cleanup effort.

Nuclear contamination from Thor Missile launch test explosion

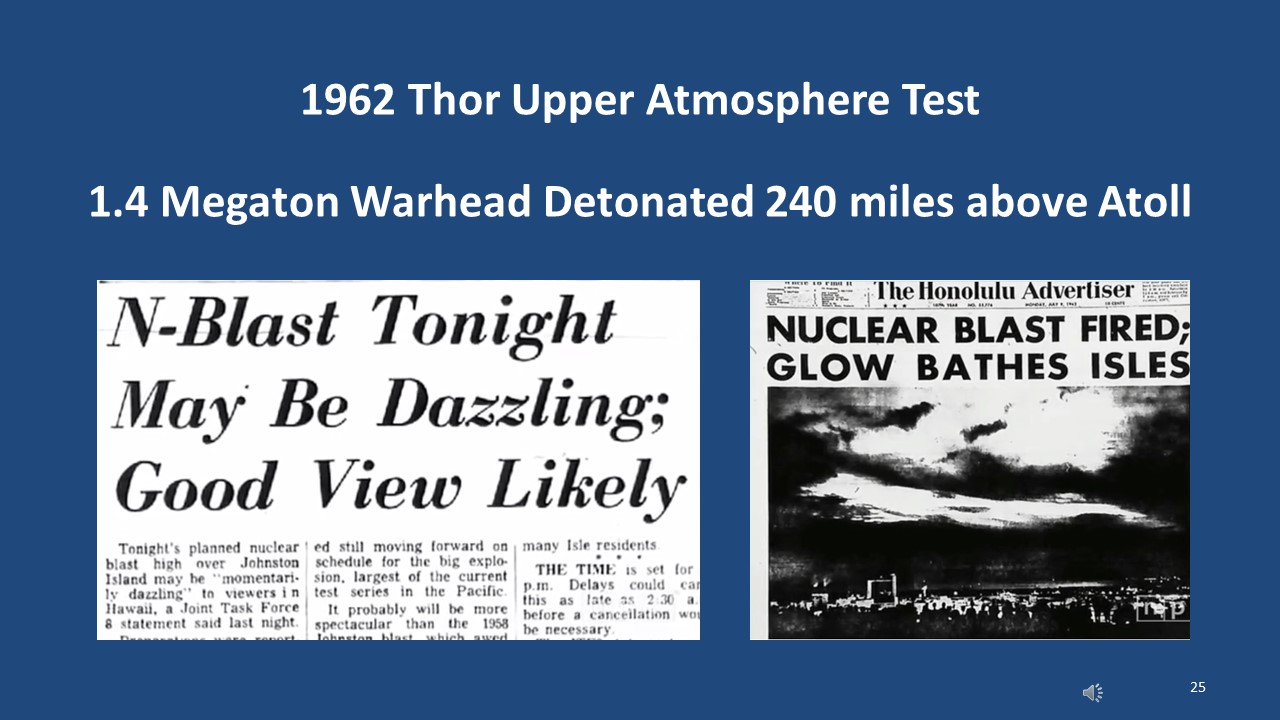

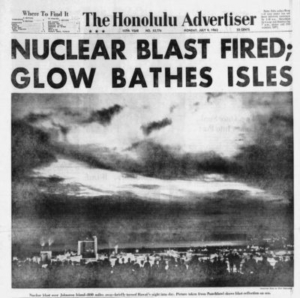

However, these early test failures were nothing compared with the spectacular 1962 nuclear explosion that was set off in the upper atmosphere 248 miles above Johnston.

The first thing this early morning nuclear blast produced was a startling artificial sunrise, an Aurora Borealis that lasted for minutes and could be seen all the way from New Zealand to Hawaii.

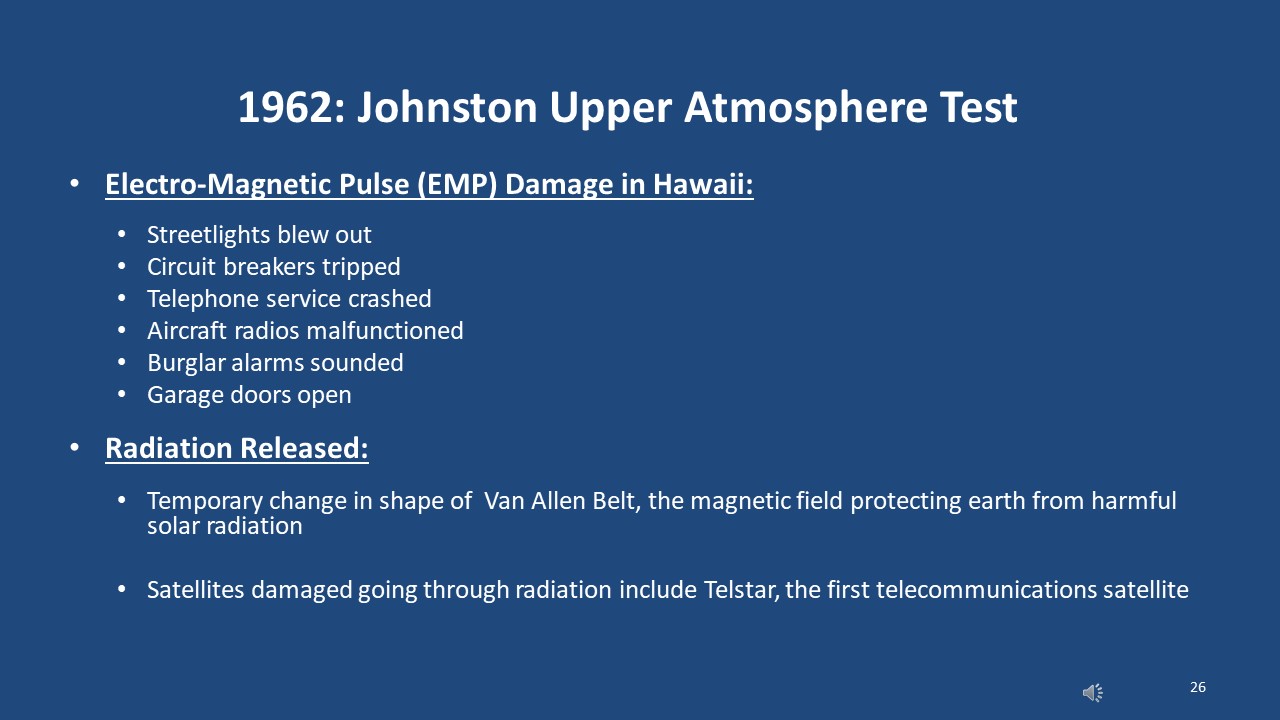

Of more consequence, no one had foreseen the startling and damaging effects of the electromagnetic pulse generated by the explosion of a nuclear device on the edge of space. On the benign side was the EMP effect that resulted in the inadvertent opening of automatic garage doors in faraway Honolulu. However, a more serious consequence of EMP effects was that the test showed a single detonation above some countries could knock out their entire electrical grid.

1962 Honolulu Advertiser reports on the nuclear test blast above Johnston Atoll

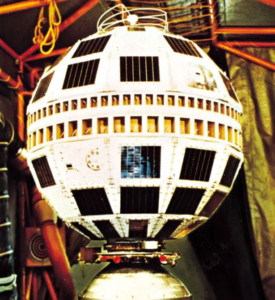

Also not foreseen was the negative impact of this detonation on the Van Allen Belt that protects the earth from solar storms, and the damage that could be caused to useful low orbit earth satellites. Among these victims, Telstar, mankind’s first telecommunications satellite, was rendered dysfunctional by the blast. The next year following this unintended result, right after the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1963, the Limited Test Ban Treaty was signed by President John F. Kennedy. It forbids nuclear tests in the atmosphere, underwater, and in space.

I had never heard of Johnston Atoll and knew none of this history while en route to Kwajalein Atoll in 1969.

As a result, as we were landing at Johnston, my jaw dropped as I noticed that on either side of the runway were rows of large Quonset-like sheds. They seemed to be connected by train tracks and outside one of the sheds was a large horizontal missile being worked on by two uniformed men.

Telecommunications satellite Telstar

I was befuddled. What was I looking at here in the middle of nowhere? There seemed to be no rational explanation for what I saw. None of my many classified briefings on our missile and anti-missile developments up to that point had even hinted at the existence of such an unusual installation. It was not until many years later that the history of this secret installation was declassified, and I learned that these all these sheds contained Thor missiles that were part of Project 437, a functional and operating anti-satellite weapon system authorized by President Johnson and fully capable of destroying Soviet satellites that might be carrying nuclear bombs. Oddly, almost at the same time as I landed at Johnston, the Air Force made the decision to shut down its anti-satellite installation.

From a counterintelligence planning standpoint, with defense troops far away in Honolulu, there had always been some concern about Johnston’s vulnerability to attack from a submarine or a commando assault in a run up to a real-world nuclear exchange. However, Johnston’s anti-satellite mission turned out to be more a victim of technological obsolescence and the increased budget constraints brought about by the still growing Vietnam War expenditures.

After we deplaned to refuel at Johnston, we had been ushered past a no-nonsense MP with his weapon drawn into a small, single-story, air-conditioned space. As we sat on plain benches waiting for the refueling to finish, it was hard not to notice the storage cubby holes on each wall and the multiple black hoses hanging down from the odd piping strung from the ceiling. Nothing was said by anyone about all this and in short order we reboarded our airplane and proceeded to Kwajalein uneventfully.

SR-71 Blackbird

As was true with my delayed knowledge of the Thor anti-satellite weapons system, it was years later that I learned that Johnston Atoll’s unique position in the Pacific Ocean made it a useful place for CIA SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft to refuel on their missions over Vietnam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and ‘70s. The Blackbirds could travel over 2,000 miles per hour and held an altitude record for flying over 85,000 feet. Their high-altitude flights required early versions of the space suits and helmets the astronauts later wore. Hence, the cubby hole storage cabinets. The ceiling pipes and related hoses were also a necessity in the Johnston ready room. They were there to feed the SR-71 pilots’ oxygen in the acclimating runup to their departure.

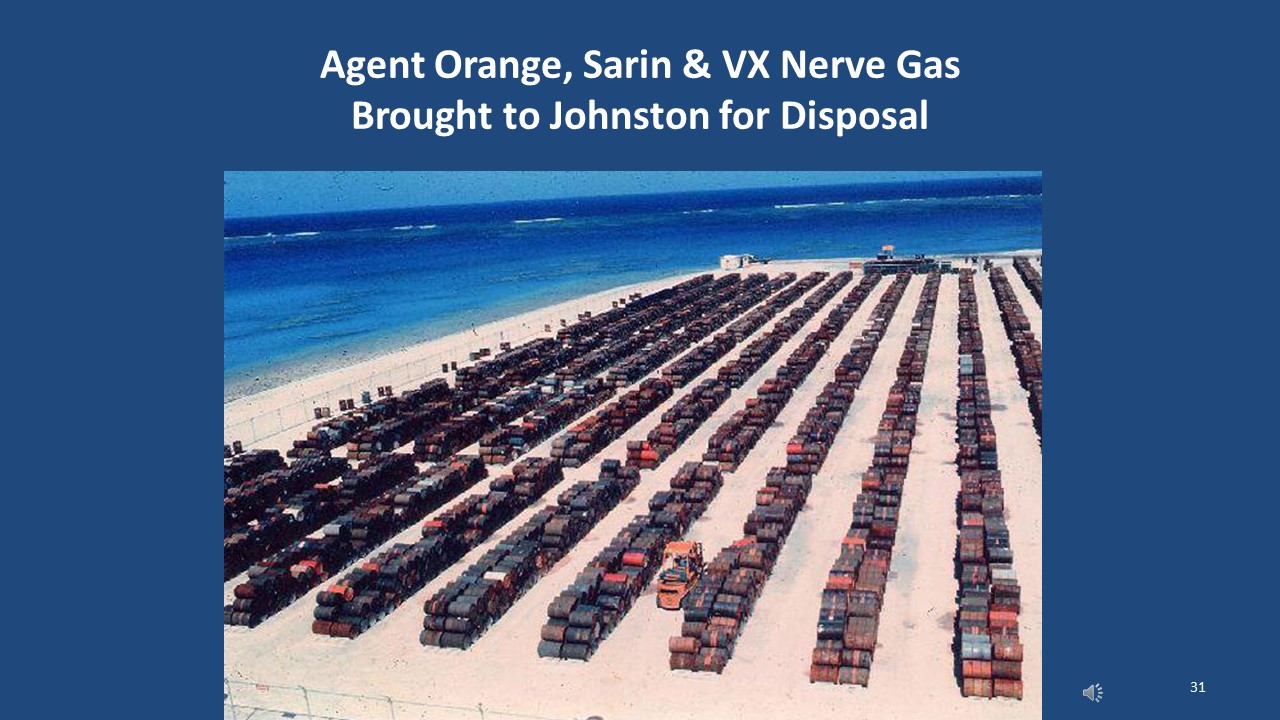

In the most recent chapter in Johnston Atoll’s history, in the 1990s Johnston was again reengaged to deal with a major national security threat. Vast stocks of aging chemical weapons secreted around the world were beginning to leak and were in danger of becoming unstable enough to explode. Johnston’s new mission became the destruction of the deadliest non-nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. It took over a decade, but an enormous furnace was built on Johnston that safely incinerated these stocks before they created an unintended disaster. At the peak of this effort, over 1,200 military and contractor personnel lived and worked on Johnston. Then, when the toxic stores were gone, all the housing and all of the other infrastructure on Johnston Atoll was destroyed and its runway shut down. Johnston wasn’t just decommissioned in 2004, it’s fair to say it was “terminated with extreme prejudice.”

So today, Johnston Atoll has reverted to its long uninhabited state and has little wildlife other than the fish that inhabit its coral reef. Knowing something today of Johnston’s history, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the fish glowed in the dark.

As our Red Tail jet took off from Johnston for Kwajalein, the then unanswered mysteries of Johnston Atoll went with me. I had a heightened curiosity as to what I’d find at my next stop. Kwajalein was an even bigger and more important outpost for the cutting-edge military technology being built at the time for the developing war theater of space.