1918 Bill Bowe, Sr. homeward bound in horse cart in Winchester, England

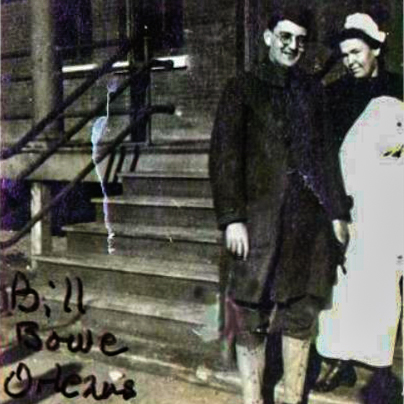

1917 William J. Bowe, Sr. recovering from foot amputation in Orleans France in World War I

Both sides of my family had members in the military. My mother’s grandfather, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Sr., lived in Covington, Georgia, and served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Among my mother’s family memorabilia was a picture of him decked out in his uniformed regalia.

In my immediate family, my father, William John Bowe, Sr., enlisted as a part-time soldier in the Illinois National Guard shortly after graduating from Loyola University law school in Chicago in 1915.

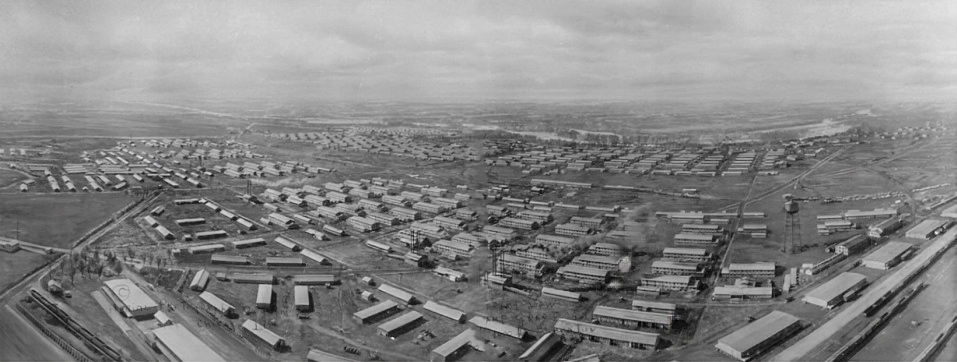

1918 National Army Training Camp Grant , Rockford, Illinois

He trained at Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois, before the U.S. entered World War I. In time he became a supply sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps. When President Woodrow Wilson called the National Guard into federal service to fight in World War I, a massive influx of draftees came into Camp Grant for training. The camp exploded in size, and in short order my father went to France with the other doughboys. Not long after his arrival in France, while trying to board a moving troop train, he slipped, and his left foot was run over by the train. The good news was that he never made it to the front, but the bad news was that he did make it to French hospitals in Blois and Orleans. The amputation of part of his foot required a long convalescence, and the war was over before he could get home.

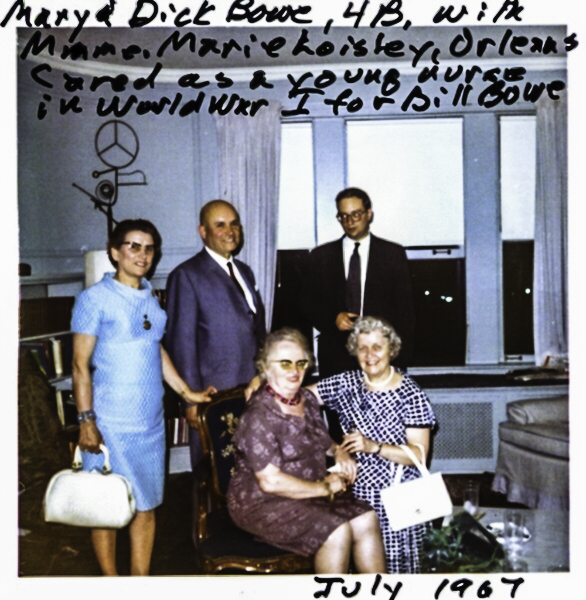

The summer of 1967, right after my law school graduation, the young French hospital nurse who had cared for my father in Orleans came to Chicago for a visit. She missed seeing her former patient, as my father had died in 1965. Nonetheless, my mother, my brother, Richard Bowe, and I had a pleasant moment as Mme. Marie Loisley reminisced about that time in the Great War.

As a young child in the 1940s, I, of course, noticed his stump and the fact he was missing his toes on one foot. When I got older, I asked him about it. He answered in a matter-of-fact way and showed me the lead insert he wore in one of his high-topped laced shoes and explained its purpose. He also let me play with his cane without complaint.

In the early 1950s, as my father entered his sixties, his cane had fallen into disuse and largely remained in an umbrella stand inside the front hall closet.

1941 John Casey, Fort Sheridan, Highwood, IL

Perhaps it was because he was no longer out and about as much. But later in the 1950s, as I was going through high school, it certainly reflected the inexorable progress of his Alzheimer’s disease and its accompanying dementia.

When World War II came along, my Uncle John Dominic Casey, recently married to my mother’s sister Martha Gwinn Casey, also served in the Army. As a child I remember visiting my Uncle John when he was recuperating from a broken leg at a military hospital in Chicago at 51st Street and the lake. After the war, the building served as the 5th Army’s Headquarters before the command was moved in 1963 to Fort Sheridan just north of the city.

1956 Richard Gwinn Bowe graduating from St Thomas Military Academy, St. Paul, MN

In the mid-1950s, my older brother, Dick, was in the Army’s Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) in high school and, like his father before him, later enlisted in the Illinois National Guard.

While my father had caught World War I, Dick was luckier. He was too late for the Korean War and too early for the Vietnam War. Between Dick and my father, it appeared to me that wars of one sort or another tended to engage American men each generation.

However, as I turned 18 and headed off to college in 1960, I thought it unlikely that I would have to follow in either Dick or my father’s military footsteps.

Richard Lawrence Gwinn (4th Georgia Volunteers)

Bill Bowe with Nurse Marie Loisley as he leaves Orleans, France hospital after recovering from foot amputation

1967 Mary and Dick Bowe with Bill Bowe, Sr.'s World War I nurse in Orleans, France Hospital