My grandfather, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Jr., was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1867. He suffered a stroke in 1929, and, to the distress of his family, he lingered without a significant recovery until he died in 1932.

Early Life and Marriage to Mary Agnes Roche

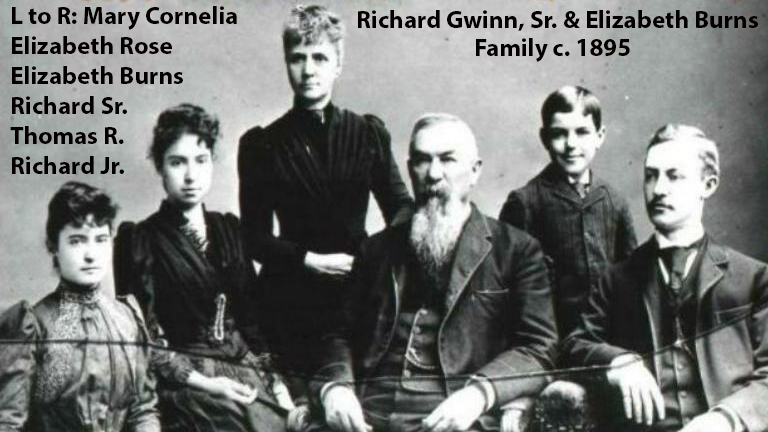

Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Jr. was the second of four children born to his father, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Sr., and his mother, Elizabeth Agnes Burns Gwinn. Two years older was sister Mary Cornelia (Page). His younger siblings were Elizabeth Rose (Bessie) Gwinn, and Thomas Ross (Tom) Gwinn. Growing up in Baltimore, he attended Calvert College there, and later pursued a career in banking and public service.

His banking career began after college when he joined the Colonial Savings and Investment Association and became associated with his lifelong friend William C. Page. This relationship no doubt played a part in Will Page’s brother George later marrying my grandfather’s sister, Mary Cornelius Gwinn.

Richard Gwinn, Jr. married my grandmother, Mary Agnes Roche in June 1900. He then immediately lost her when she died giving birth to my mother, Mary Agnes Gwinn Bowe, just nine months later, in March 1901.

Richard Gwinn, Sr & Elizabeth Burns Family c. 1895

Mary Agnes Roche Gwinn in 1900

Early life and marriage to Mary Agnes Roche

My grandfather, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Jr., was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1867. He was the second of four children born to his father, Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Sr., and mother, Elizabeth Burns. Two years older was her sister Mary Cornelia and her younger siblings were Elizabeth Rose (Bessie) and Thomas Ross (Tom). Growing up in Baltimore, he attended Calvert College, then pursued a career in banking and public service. He suffered a serious stroke in 1929, and without really recovering, died in Baltimore in 1932.

His banking career began after college when he joined the Colonial Savings and Investment Association and partnered with lifelong friend William C. Page. This relationship no doubt played a part in the fact that Will Page’s brother, George, later married my grandfather’s sister, Mary Cornelius Gwinn.

Richard Gwinn, Jr. married my grandmother, Mary Agnes Roche in June 1900. He then lost her immediately when she died giving birth to my mother, Mary Gwinn, nine months later in March 1901.

Banking Career

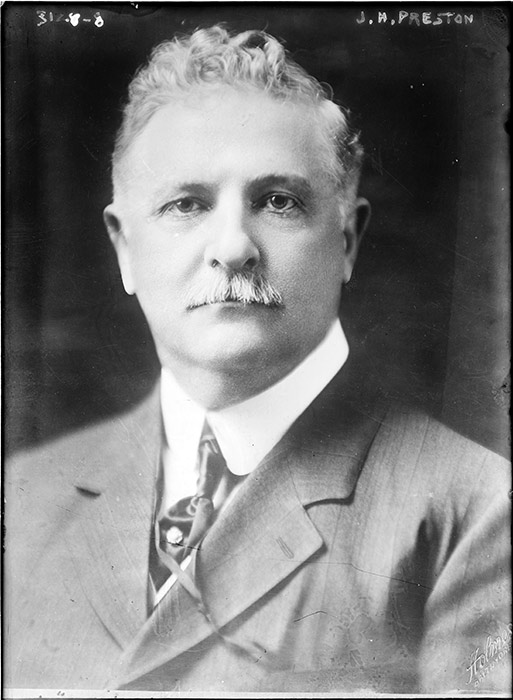

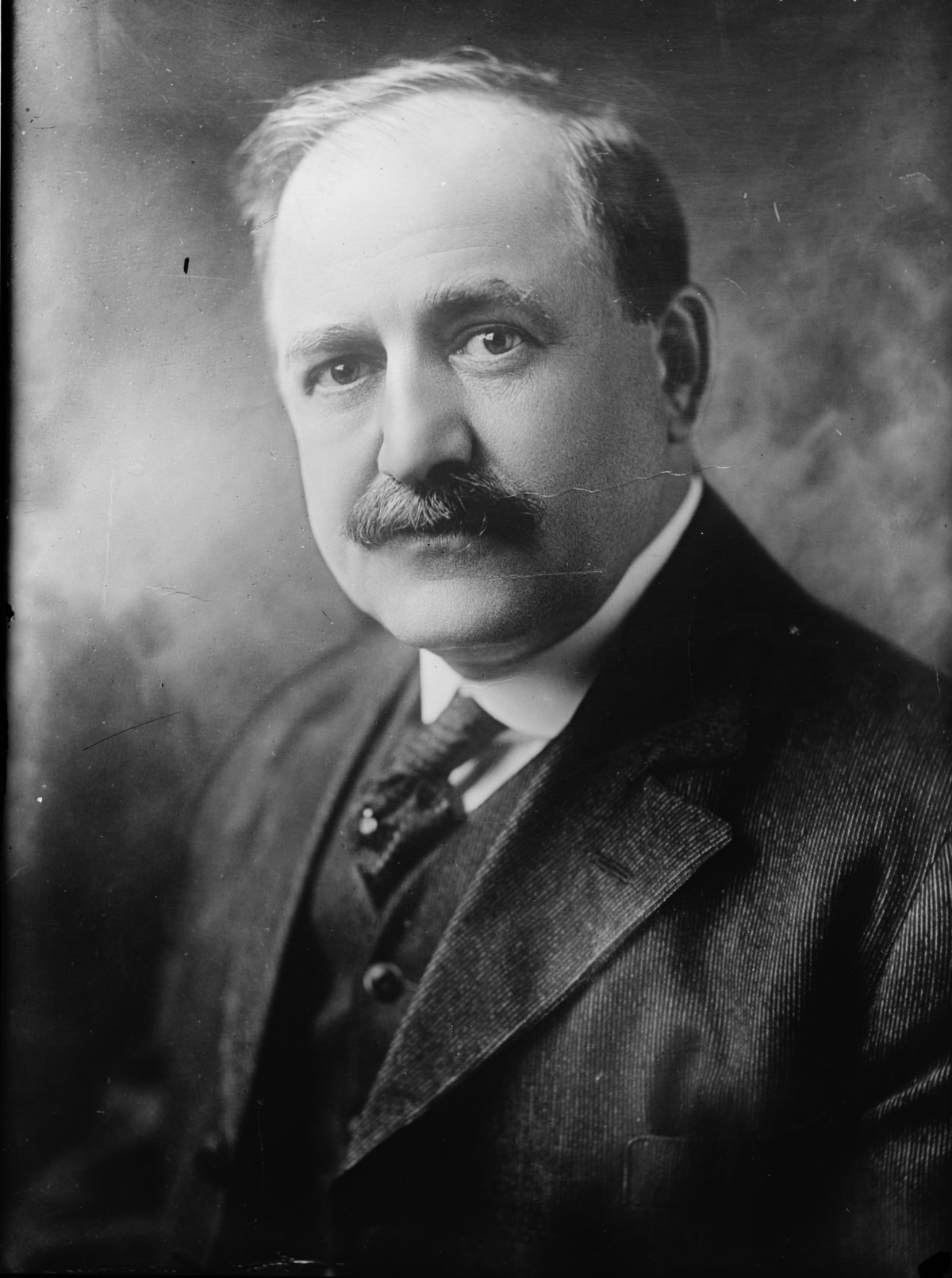

That same year, my grandfather helped found the Calvert Bank in Baltimore. Will Page was the bank’s president, James Preston was later president, then vice president and attorney, and Richard Gwinn was second vice president.

Democrat James Preston would later serve three terms as mayor of Baltimore, and my grandfather was elected three times to serve 12 years as the Baltimore Register, as city treasurer is more commonly.

The Stafford and Belvedere Hotels

During her six years of widowhood, Richard Gwinn shared bachelor quarters with his friend Grafflin Cook at the Stafford Hotel at 716 Washington Place in Baltimore. Although I remember almost nothing of the trip, in 1946, when I was four years old, I went with my parents and my four-year-old older brother Dick (Richard Gwinn Bowe) to Baltimore for the funeral of Elizabeth Tack. Gwinn, my grandfather’s widow. We stayed at the same Stafford Hotel where my grandfather had lived with Grafflin Cook. I remember nothing of the funeral or the visitation, other than an extravagant family gathering for a meal in the dining room of the nearby Belvedere Hotel on One Chast Street. No four-year-old could ever have been more fascinated than I by an ornately decorated gingerbread castle as a centerpiece.

Co-Executor of the Samuel G.B. Cook Estate with George Weems Williams

My grandfather’s relationship with Grafflin Cook later brought an unexpected duty. Cook’s father, Samuel G.B. Cook, had made his fortune by acquiring the rights to manufacture and sell the revolutionary and newly patented bottle stopper. My mother described him as “the founder, father and maker of all bottle caps for everything.” When Samuel Cook died in 1919, Richard Gwinn was in charge of administering his estate. His co-executor of the estate was George Weems Williams. Williams would defeat Mayor James Preston in the 1919 Democratic primary election, before losing in the general election to William Frederick Broening, a Republican. Cook’s main assets, worth more than a million dollars, were shares in what was then known as the Crown, Cork and Seal Company. An estate of this size would normally produce substantial fees for executors.

Family with Elizabeth Tack Gwinn

In 1907, my grandfather remarried. His second wife was Elizabeth Cosgrave Tack, whose family lived in New York. My mother’s half-sisters were Elizabeth (Betty), Martha and Anne Chesley, who was always called Nancy. The family lived at 1809 Dixon Road in the Mt. Washington section of Baltimore.

Elizabeth Burns Gwinn was Richard Gwinn, Jr.’s mother and my mother’s grandmother. She was responsible for raising my mother, who always called her “Mama.” Portraits of Elizabeth Burns Gwinn and her husband, Richard Gwinn, Sr. hang in my dining room are in Northbrook, Illinois today, just as they once hung in the dining room at 1809 Dixon Road over a century ago. In her early years, my mother usually lived with her grandmother in an apartment on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, DC. Summers were spent in a rooming house her grandmother ran at 58 Sydney Street in Deal, New Jersey. During her high school years, while attending Asbury Park High School, my mother lived year-round in Deal. However, once Richard Gwinn, Jr. remarried, she enjoyed becoming an older sister with three younger siblings. Now she visited her father’s new family frequently, and remembered being warmly embraced by her new stepmother. According to my mother’s account, her stepsisters Betty, Martha and Nancy were as thrilled as she was with their time together. And, from my observations over the years of witnessing their interactions, they have always been full sisters to each other. There was no half-heartedness or side-stepping in the relationship between these four that I have ever seen.

Election as Baltimore Register

During the 12 years my grandfather served as treasurer of Baltimore, his actions and the finances of the city were often the subject of commentary in the Baltimore Sun newspaper. As an example, on March 26, 1914, The Sun reported: “Baltimore will be placed on the financial map of the world if the recommendations of the City Register Richard Gwinn are adopted, as they should be. In May of the same year, a Sun article headline read: “Gwinn Re-Named City Register.”

Describing Gwinn’s response to the subsequent announcement of a tax assessment, the Sun wrote, “Mr. Gwinn insists…and points out the benefits. Declares that the owner whose property has been upgraded has received a gratuity. Reporting on a different refinancing of the city’s bonds, the Sun wrote: “The tale is like a drama…interest paid to the city…”

On May 24, 1915, the Sun’s verdict was clear: “Re-elect Gwinn as Register tomorrow” and “Unanimous Council Action Expected.” His work ethic was also praised by The Sun, which noted that in the previous four years he had only been away one day and worked ten Sundays, “an unparalleled record”. With this accumulation, it is not surprising that two days later, the Sun reports: “Gwinn Again Register, Receives Unanimous Vote”.

The city’s finances at the time remained difficult. The following year, on August 15, 1916, the Municipal Journal wrote: “During the past year, the tax agents of the City have had a financial problem to solve which required skill and ingenuity to accomplish…” The description continued:

“The solution to the problem fell largely on the shoulders of Mr. Richard Gwinn, the City Register. He saw what was to come and he began to lay out his plans as early as 1914. As a competent and experienced financial agent, he laid out a plan and then executed it with such ease and success that the public was barely aware of the fact.”

Landing Charles Schwab’s Bethlehem Steel Mill at Sparrows Point Perhaps Richard Gwinn’s greatest accomplishment in his twelve years as Baltimore Treasurer was helping convince New Yorker Charles Schwab to build a Bethlehem steel mill on Baltimore Harbor at Sparrows Point. My mom says her dad flew to New York to visit Schwab informally at his Riverside Drive home.

At 18, Schwab had started working as an ordinary laborer in one of Andrew Carnegie’s steelworks. At 21, he was chief engineer. At age 35, he became president of the Carnegie Steel Company. Then, in 1901, the same year my mother and Calvert Bank were born, Schwab helped organize the U.S. Steel Corporation and moved from Pennsylvania to New York.

In 1904 he took over and another steel company, incorporated as Bethlehem Steel Co. Wealthy on the scale of Carnegie and Henry Frick, Schwab in 1905 built a house in New York City to meet his needs. Just as Schwab was no ordinary financier or man of steel, his residence was no ordinary house. It occupied a full block along the Hudson River frontage stretching from the West End to Riverside Drive between 73rd and 74th Streets in midtown Manhattan. Plus, it was a 75-room, 50,000-square-foot house in the style of various French chateaux. It also sported a gym, bowling alley, swimming pool, three elevators, and interiors in the styles of Henri IV, Louis XIII, Louis XV, and Louis XVI. My mother wrote that her father “enjoyed playing the beautiful built-in organ seemingly as much as he enjoyed pursuing the financial goals of travel.” The result was that Charles Schwab thought Baltimore had made a good case for him to build the mill he had in mind there. He also concluded that Sparrows Point on the harbor, just south of where the army established Fort Holabird, was the correct site. It had a deep-water port that the old factory had used to unload iron ore originally brought by steamships from Cuba. It also had the potential to add rail access for the delivery and shipping of raw materials. Also, the Mayor, Register, and business leaders in Baltimore were more than welcoming. With Schwab’s die-casting on November 21, 1916, all stops were pulled by locals when 300 Baltimore leaders celebrated his decision with an elegant dinner in his honor at the Belvedere Hotel.

In 1918, the factory was operational and by mid-century it employed 20,000 workers. The Sparrows Point plant faded away at the turn of the 21st century and Bethlehem Steel declared bankruptcy, eventually closing the plant in 2012. This put the last 2,000 workers out of work.

Family visit to Atlanta, Conyers and Covington, Georgia

With the mill secured for Baltimore, in March 1918 Richard Gwinn traveled to Birmingham, Alabama to represent Baltimore at a convention of the Southern Sociological Congress. On his way back to Baltimore, he stopped in Atlanta, Georgia to visit his uncle Robert Gwinn, his father Richard Gwinn, Sr.’s brother. He also made time to spend a day in visiting other relatives he hadn’t seen in 30 years in Conyers and Covington, Georgia.

The Arrival of the “Spanish Flue” in 1918 By the end of 1918, the Spanish flu had arrived. According to the federal government’s Center for Infectious Diseases website in 2022, it was even deadlier than the COVID-19 virus that rocked the United States a century later. It is estimated that around 500 million people, or a third of the world’s population, were infected with this virus in the 1918-1919 period. The number of deaths has been estimated at at least 50 million worldwide, including around 675,000 in the United States. Mortality was high in people under 5, those 20-40, and 65 and older. High mortality among healthy people, including those in the 20-40 age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic.

My mother explained how the flu affected the family that year:

“In December, everyone had the ‘flu.’ It was the great epidemic. At Deal, I was cared for by both my grandmother and then by Bessie [her aunt Elizabeth Rose Gwinn] and my father was very worried that we were home alone with fires to tend, and that I was at school from eight o’clock to one o’clock. We closed as soon as they could move and we went to Asbury, where I immediately went down with it”.

Retirement of Mayor Preston and Re-election as the Baltimore Register

During World War I, Richard Gwinn regularly joined his friend Mayor Preston at rallies selling war bonds. During a changing of the guard for mayor in 1919, fellow Democrat and close colleague over the years, Mayor James H. Preston lost the Democratic primary election for Mayor in 1919 to George Weems Williams, Richard Gwinn’s co-executor for the Cook estate.

As my grandfather ran again for Register, my mother says he was surprised to be supported in the effort by Republicans. It certainly helped that before the election, the Sun published a letter to the public signed by 45 banks and financial houses endorsing him for another four-year term as Baltimore’s treasurer. The letter read in part: “Mr. Gwinn has administered this office for eight years with singular skill, and we respectfully suggest that there is no good business reason for a change at this time. Therefore, we most sincerely request your honorable bodies, in joint session, to re-elect Mr. Richard Gwinn City Register.”

A Gun for Mexico City

The following year, 1920, he traveled to a convention of bankers in Mexico City, returning home via California, Oregon and Washington State, before heading east again to across Canada on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Concerned about his safety on this trip, he bought and packed with his belongings a nickel-plated revolver. When I was in high school, my mother showed me her hiding place for the weapon in our apartment. The gun and its bullets were hidden behind books in hall bookcase.

Many years later, in 1980, Cathy and I briefly returned to the Elm Street apartment when our son Andy was born. I didn’t want to keep a gun and ammunition around young children, so when I had the opportunity to do so at a “Gun Day” at the Chicago Avenue Police Station, I went in to give it up. The duty policeman was struck by the antique nature and shining beauty of Richard Gwinn’s pistol. He offered on the spot to buy it personally. The cop got the gun, I got $20, and we both went away happy.

Richard and Elizabeth Tack Gwinn visit Chicago

After my mother and father were married in 1928, Richard Gwinn and his wife Elizabeth took a trip to Chicago to see if the new couple were safely settled down. they were indeed.

His Stroke, Death, and a Look Back at the Life of Richard Lawrence Gwinn, Jr.

Recalling his stroke in summer 1929, and his death in 1932, my mother offered this summary of his father:

“Besides his one trip to Europe with Mary [Mary Cornelius Gwinn Page, his sister], he managed a reasonable number of trips. However, he was never a restless person, and I have never known a calmer and more methodical man, more free from fads and notions, or happier to simply be well and enjoy his family. and his house.”