Subchapters

- Riots & Rockets Army Days Map (1968-1971)

- Family in the Military

- The Vietnam War Heats Up

- The Decision to Enlist

- Fort Holabird and Intelligence Training

- CIAD in the CD of OACSI at DA in DC

- The Vance Report

- Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations

- Bernardine Dohrn-The SDS Revolutionaries Then and Now

- The Army Operations Center (AOC)

- The Blue U and CIA Training

- The Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System

- Huntsville, Alabama, and the Army Missile Command

- NORAD and Cheyenne Mountain

- Johnston Atoll and the Origins of Space Warfare

- Kwajalein Atoll—The Ronald Reagan Missile Test Site

- Kent State University and the Aftermath

- Yale, The Black Panthers, and the Army

- The Secretary of the Army’s Special Task Force

- Getting Short—The 1971 Stop the Government Protests

- 1974 Congressional Hearings on Military Surveillance

- Lunch with Gen. William Westmoreland

Kwajalein Atoll—The Ronald Reagan Missile Test Site

Kwajalein Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands

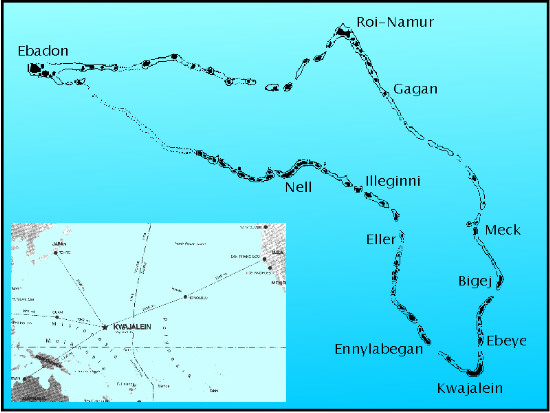

Our plane landed on Kwajalein Island, the largest and southernmost island in the Kwajalein Atoll. Kwajalein is due north of New Zealand in the south Pacific and due east of the southern part of the Philippines. In short, like Johnston Atoll, it’s in the middle of nowhere. The Atoll is made up of about 100 islands in a coral chain 50 miles in length, stretching from Kwajalein Island in the south to Roi-Namur Island in the north. Kwajalein Island is only three quarters of a mile wide and three and a half miles long. The whole of the Atoll’s coral land is only 5.6 miles square. The Atoll is about 80 miles wide, which makes it one of the largest lagoons in the world.

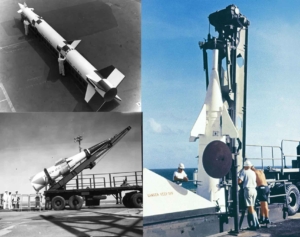

Top and right: Exo-atmospheric Spartan missile. Lower left: Short range Sprint missile

The people I most needed to talk to on Kwajalein were the senior Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientists and Raytheon engineers most familiar with the Safeguard missile development (both the short-range Sprint Missile and the exo-atmospheric Spartan Missile). I also needed to learn more about the functioning of the Phased Array Radar (PAR) central to Safeguard’s ability to track and intercept incoming warheads before vaporizing them with X-rays from a nuclear detonation.

Meck Island Perimeter Acquisition Radar under construction

My interviews on Kwajalein Island and Roi-Namur were delayed due to my being bumped by a Congressional staff visit that happened to conflict with mine. Recent glitches in the Safeguard testing had apparently triggered a closer Congressional look at the state of the program and its related budgeting problems.

To have something to do in the meantime, my Army host, who also served as the base recreation officer, took me out to golf. What a course! It lay on either side of Kwajalein Island’s single runway. The narrow greensward where you could play was studded with radars used in the Island’s missile testing work. The so-called fairways had a picket fence on their ocean side that served as a no-go reminder. Should your golf ball go over the fence and plop down in front of one of the munitions storage bunkers there, you might have to kiss it goodbye. However, by the fences were long poles with a circular ring on the end. If it reached your mis-hit ball, you could retrieve it. If the pole couldn’t reach your ball, you were SOL.

Kwajalein radar repurposed as a golf driving range

There was not the same problem at Kwajalein’s golf driving range. There was no way you could lose your golf ball there. That’s because the range had repurposed an enormous and abandoned circular radar structure. The radar’s construction had created a giant circular steel mesh so tall, and with such a large diameter, that no matter how hard you might hit a golf ball from the radar’s perimeter, you couldn’t knock it out of the enclosed space. This was no doubt the most expensive golf driving range ever built by mankind.

On one of our golf outings by the runway our play was interrupted by loud klaxon horns atop the many radars on the greensward. “What the hell is that?” I asked. My minder said that it was a warning that powerful, potentially harmful radar waves would soon be sweeping our fairway or perhaps there was a danger of debris from an incoming or outgoing test missile, and we needed to immediately take shelter. Believe me, he didn’t have to tell me twice!

One evening after dinner I strolled down to the small harbor at nightfall. It was quiet and peaceful looking out at the lagoon. Soon I noticed another man out for an evening stroll. We struck up a conversation and I asked him what he did on Kwajalein. He said he was just visiting from California and that he was looking forward to the incoming ICBM later that evening. That was news to me, so I asked him how he knew about that. He said that he was the person who had programed the instrument package that replaced the ICBM’s warhead for the test. He said this was his first opportunity to see the fireworks above Johnston as the incoming missile and his package headed through the atmosphere to preprogrammed coordinates in the lagoon. I quickly decided I too would stay up late for the fireworks. Sadly, when I woke up the next morning, I had to kick myself for sleeping through the night and missing the big show.

One of the issues that surfaced in my later counterintelligence report had to do with a Soviet spy ship, disguised as a fishing trawler. It permanently lingered just outside the Atoll in international waters. There, it constantly monitored the telecommunications of all the personnel on Kwajalein, as well as the telemetry of every rocket test. Besides the communication security protocols in place to minimize the value of the trawler’s signals intercepts, another very important procedure related to the spy ship had been put in place. When an incoming instrument package had separated from its ICBM and fell into Kwajalein’s lagoon, at least three splash detection radars at different points on the Atoll would triangulate the precise location of the splash. This permitted an assessment of whether the accuracy of the missile launch was sufficient to destroy a hardened Soviet ICBM silo in the U.S.S.R. In a further security step, swimmers would immediately dive into the lagoon at the impact point and recover the instrument package and its data. This was a protocol to ensure no divers from the Soviet intelligence ship would ever beat them to the punch.

Meck Island Phased Array Radar

When the Congressional folks who had delayed my work hit the road, I caught the first available twin-engine commuter flight up to nearby Meck Island on the Atoll. Here was Safeguard’s recently constructed Phased Array Radar that I needed to understand better. The large radar had a fixed and circular slanted face that permitted it to scan incoming missiles launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Air Force crews, plucked at random from Montana or other ICBM installations, would be trucked with their Minuteman missiles to Vandenberg. At Vandenberg, their launch proficiency would be tested, and the missiles were regularly topped off with instrument packages instead of warheads before being launched at a predetermined point in Kwajalein’s lagoon.

As the Meck Island manager took me into the outsized computer room that formed the base of the large radar, he smiled, and, in a voice like that of a proud father talking about a child bringing home a good report card, he said that there was more computing power in that room than existed on the entire planet in 1955.

Roi-Namur Island

As I digested the meaning of that, the thought occurred to me that he might in fact be telling me the truth.

From Meck, I flew up to Roi-Namur Island on the north end of the atoll. There were different radars and instrumentation issues I needed to learn about at that location as well. With my fieldwork complete, I was ready to go home to Washington, D.C., and write my report. I quickly caught the last commuter flight of the day at Roi-Namur and flew the 50 miles south back to my Bachelor Officers Quarters (BOQ) accommodations on Kwajalein Island. Without delay, I was on the next red-tail Northwest jet that came through Kwajalein to shortly begin a week’s leave from the Army in Honolulu visiting a college classmate and his family.

Roi-Namur radars

Upon my return to the Pentagon, I spent several weeks doing further research. Then I turned for several more weeks to writing up my report on the Safeguard System’s espionage and sabotage vulnerabilities and the steps necessary to further harden the System’s operational weaknesses. In late fall 1969, I completed my assignment by providing briefings on my report to the Safeguard Security Working Group, other senior Army officers, and various civilian technical and scientific advisers.

My effort must have met with approval as the Commanding Officer of the 902nd Military Intelligence Group awarded me at year-end a Certificate of Achievement for “exemplary duty” for this work. To me, that meant that the report had probably been more useful than anyone had imagined it would be when I was first assigned the task.