Subchapters

- Riots & Rockets Army Days Map (1968-1971)

- Family in the Military

- The Vietnam War Heats Up

- The Decision to Enlist

- Fort Holabird and Intelligence Training

- CIAD in the CD of OACSI at DA in DC

- The Vance Report

- Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations

- Bernardine Dohrn-The SDS Revolutionaries Then and Now

- The Army Operations Center (AOC)

- The Blue U and CIA Training

- The Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System

- Huntsville, Alabama, and the Army Missile Command

- NORAD and Cheyenne Mountain

- Johnston Atoll and the Origins of Space Warfare

- Kwajalein Atoll—The Ronald Reagan Missile Test Site

- Kent State University and the Aftermath

- Yale, The Black Panthers, and the Army

- The Secretary of the Army’s Special Task Force

- Getting Short—The 1971 Stop the Government Protests

- 1974 Congressional Hearings on Military Surveillance

- Lunch with Gen. William Westmoreland

Bernardine Dohrn-The SDS Revolutionaries Then and Now

Bernardine Dohrn Attends the Class of 1967’s 55th Reunion of the University of Chicago Law School

Bernardine Dohrn Takes Questions from her Law School Classmates in 2022

Family Ties Prove Bill Ayers’ Point

1968 Viet Cong interrogation training exercise at Ft. McHenry, Baltimore

In this short period of time, another major factor began to enter into my professional purview besides the continuing deterioration of race relations in the country. This new factor had a lot to do with what one of my University of Chicago Law School classmates had been up to in her year since graduation.

Assigned to the Pentagon in support of the Directorate of Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations

Bernardine Dohrn had earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and had been one of the small number of women who entered the University’s law school with me in fall 1964. Our law school class had 150 incoming students. While most of the first-year students wore trousers, Bernardine stood out with both her miniskirts and her politics.

The summer after our second year in law school, my brother Dick was working for the City’s Commission on Human Relations. A large rent strike with racial overtones was underway at the former Marshall Field apartment complex in the city’s Old Town neighborhood. I was interested in landlord/tenant law reform at the time, so I took my brother up on his invitation to join him in looking at what was going on. At the site, I found my classmate Bernardine by the picket line.

While I was there out of a largely academic interest, Bernardine explained she was there to directly assist the cause of the rent strikers and show her solidarity with the tenants.

The only other law school contact with Bernardine I recall was when I pulled a group of classmates together to help prepare a traditional third-year spring skit. The goal of the exercise was always to relieve some of the tensions of upcoming final exams by poking fun at student obsessions of the day and making sport of notable faculty. I’m not sure why Bernardine turned up, because she found absolutely no humor in any of the subjects put on the table for discussion and took no further part in the effort.

While I was in no position to conclude from this that Bernardine was humorless, looking back on much of the language Bernardine later came to use, it occurred to me that it might be difficult to find anything to laugh about if you’re a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary committed to using violence to overthrow the U.S. Government because it’s a racist, imperialist, capitalist, misogynist, and xenophobic regime with its white supremacist jackboot on the oppressed necks of the under trodden.

Following graduation from law school in 1967, Bernardine took a job organizing law students for the left-wing National Lawyers Guild and became active in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In June 1968, just as I entered Intelligence School, she became the Interorganizational Secretary of SDS, and just three months later, SDS played a role in the violence that broke out in Chicago during September’s Democratic National Convention. The ensuing battles of anti-war demonstrators with police and National Guard in the Convention’s run-up drew a worldwide television audience.

In December 1968, Bernardine helped lead a celebration in New York City of The Guardian newspaper’s 20th anniversary. The Guardian had a Maoist bent and was then a prominent weekly organ of the New Left. Her co-host at the gathering was Herbert Marcuse, a leading academic philosopher of revolutionary upheaval then teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In her remarks, Bernardine denominated Marcuse as “the ideological leader of the New Left.” Marcuse in his own remarks went on to envision the New Left’s coming “political guerrilla force.”

In this increasingly roiled political atmosphere, large scale anti-war demonstrations and anti-government violence in the form of bombings and arson events began to loom large as I prepared my estimates on the likelihood of the President having to deploy Regular Army troops in a civil disturbance control mission. Indeed, in one 18-month period in 1971-72 alone, over 2,500 domestic bombings were cataloged. This new development of broad-scale political unrest joined the extant racial violence as possible contributors that might call for Regular Army troops to supplement police and National Guard forces in a domestic peacekeeping role.

In June 1969, Bernardine Dohrn led a split in the SDS at its national convention in Chicago and, in an accompanying manifesto, Bernardine and her Third World Marxists group in SDS advocated street fighting as a method for weakening U.S. imperialism. The Third World Marxists presented a position paper titled “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows” in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes. The position paper title was taken from a song by Bob Dylan and argued that Black liberation was central to the movement’s anti-imperialist struggle. It explained the need for a white revolutionary movement to support liberation movements internationally.

The manifesto became the founding statement of the SDS Weatherman faction. The Weather Underground, as the hard-core group soon called itself, quickly became responsible for what it called the Days of Rage violence in Chicago in October 1969.

The premise for this mayhem was the commencement of a criminal trial of the Chicago Seven, leaders of the Chicago Convention violence the prior year. Not long after this, the Weather Underground followed with bombings of the United States Capitol, the Pentagon, and several police stations in New York, as well as a Greenwich Village townhouse explosion in New York City that killed three Weather Underground members. Along the way, Bernardine was quoted as announcing, “I consider myself a revolutionary communist.”

With these events unfolding, Bernardine appeared as a principal signatory of the Weather Underground’s “Declaration of a State of War” in 1970. This document formally declared “war” on the U.S. Government. Having confirmed the group’s dedication to revolutionary violence, Bernardine went on to record the declaration and send a transcript of it to The New York Times. In my role providing intelligence support to DCDPO, among other open and classified materials, I read a steady flow of Federal Bureau of Investigation reports on internal security matters. For decades the FBI had focused its counterespionage and countersubversion resources on the Communist Party of the United States.

By the late 1960s, however, CPUSA, as the acronym had it, had faded in the priority list of targets. It had been displaced in importance by what was termed by the FBI as the New Left. So it was that a little over a year following my law school graduation, fat FBI dossiers on my classmate Bernardine Dohrn and her later husband, Bill Ayers, landed on my desk in the new Army Operations Center.

These reports on Dohrn and Ayres were typical background compilations. As the pair’s bent towards violence increased, so did the FBI’s surveillance activities. In a major embarrassment for the FBI, the government’s misconduct and overreaching in this regard resulted in them escaping punishment for the serious criminal charges they faced.

The Weather Underground Days of Rage battles with police in Chicago in October 1969 had produced a count of three shot and more than three hundred demonstrators arrested. Ready to plan next steps, Bernardine helped organize a “war council” for the group in Flint, Michigan, at the end of the year. Not surprisingly at this point, the FBI had been able to infiltrate a confidential informant into the proceedings.

In remarks attributed to her, Bernardine is said to have made passing reference to the recent Los Angeles murders of movie director Roman Polanski’s wife, Sharon Tate, and four others by cult followers of Charles Manson: “Dig it! First, they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them. They even shoved a fork into the victim’s stomach! Wild!”

In a further sign of how far out revolutionary fantasies were becoming, the FBI informant reported on conversations on the need down the road to establish post-revolution reeducation centers in the Southwest when the time came to turn recalcitrant capitalists into right-thinking supporters of the new order.

About the same time the Flint war council was going on, I had the duty as agent for my law school class to solicit my classmate Bernardine for an alumni contribution. Under the circumstances of the day, I’m sure you can appreciate why I thought this was likely a bridge too far. Nonetheless, I dutifully wrote to her at her last known address and made the only argument I thought might elicit a contribution. I told her any amount she could afford would go to buy out the teaching contract of a widely unpopular law professor. My ploy failed when my Dear Bernardine Letter was returned as undeliverable.

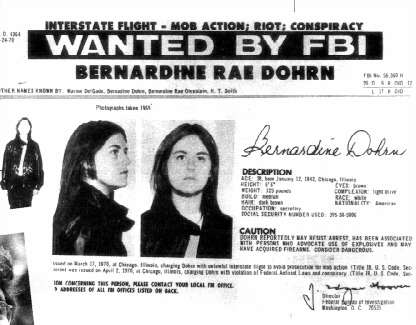

I was not the only one trying to get in touch with Bernardine at the time. On March 17, 1970, a federal arrest warrant was issued charging her with interstate flight to avoid prosecution for mob action, riot, and conspiracy. Though FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover put her on the FBI’s 10 most-wanted list, Bernardine was nowhere to be found. She had gone to ground.

Though Bernardine was on the lam and out of sight, she made sure the Weather Underground was not completely out of mind. In 1974, she, Bill Ayers, and Jeff Jones published 40,000 copies of their manifesto, Prairie Fire, so called from Mao Zedong’s revolutionary slogan, “a single spark can start a prairie fire.”

Distribution was made through college bookstores, left-wing organizations, and similar outlets likely to reach their most sympathetic audience. Prairie Fire laid out the then-radical idea that the underlying principles of the American Revolution were capitalism, racism, sexism, imperialism, and colonialism. It also explained that white supremacy was being perpetuated “by the schools, the unemployment cycle, the drug trade, immigration laws, birth control, the army, the prisons,” and “white-skin privilege.”

With the bombing of government targets a then-failed strategy for the revolution, the new strategy laid out in Prairie Fire was to focus on America’s educational system. The manifesto called on radical teachers to coalesce as an “anti-racist white movement” within the educational system to radicalize other teachers and bring about a completely new educational environment for the students in their charge.

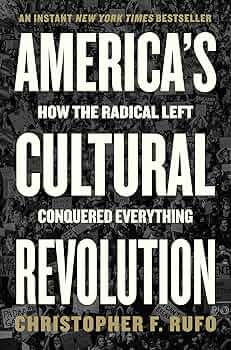

In his book America’s Cultural Revolution, conservative author Christopher Rufo observed that though the Prairie Fire tract didn’t revive the fading New Left in the 1970s:

In his book America’s Cultural Revolution, conservative author Christopher Rufo observed that though the Prairie Fire tract didn’t revive the fading New Left in the 1970s:

Over time it would become the entire vocabulary of American intellectual life: “institutionalized racism,” “white supremacy,” “white privilege,” “male supremacy,” “institutional sexism,” “cultural identity,” “anti-racism,” “anti-sexist men,” “monopoly capitalism,” “corporate greed,” “neocolonialism,” “Black liberation.”

The next year Bernardine surfaced again, this time as the author of a Weather Underground magazine article “Our Class Struggle.” It was said to be based on a recent speech given to Weather Underground cadres. While some precincts of the New Left had tended by this time to play down some of the traditional communist party rhetoric as beginning to sound out of step and old fashioned, this article was certainly a reversion to the older Marxist-Leninist argot:

“We are building a communist organization to be part of the forces which build a revolutionary communist party to lead the working class to seize power and build socialism. … We must further the study of Marxism-Leninism within the WUO [Weather Underground Organization]. The struggle for Marxism-Leninism is the most significant development in our recent history. … We discovered thru our own experiences what revolutionaries all over the world have found—that Marxism-Leninism is the science of revolution, the revolutionary ideology of the working class, our guide to the struggle …”

By 1980, Bernardine and her Weather Underground cohort Bill Ayers were raising children and were tired of the underground life. They surrendered. Bernardine pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of aggravated battery and jumping bail but served no time for these offenses. Bill Ayers faced more serious charges, but they were dismissed on grounds of government misconduct.

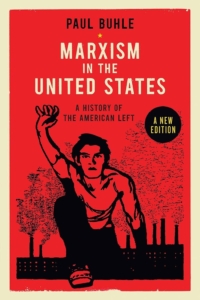

The later career trajectories of Dohrn and Ayers put truth to the observation made by Paul Buhle, a scholar from the left. In his book Marxism in the United States: “To the question: ‘Where did all the sixties radicals go?,’ the most accurate answer would be: neither to religious cults nor yuppiedom, but to the classroom.”

The later career trajectories of Dohrn and Ayers put truth to the observation made by Paul Buhle, a scholar from the left. In his book Marxism in the United States: “To the question: ‘Where did all the sixties radicals go?,’ the most accurate answer would be: neither to religious cults nor yuppiedom, but to the classroom.”

True to this form, though never admitted to practice law in any state, Bernardine went on to teach in the clinical practice of Northwestern University Law School in Chicago. Bill Ayers went on to teach in the education department of the University of Illinois Chicago. They receded from the public eye for years but roared back into the headlines in 2008 when Barack Obama ran for president, and it was revealed that one of his early backers was Ayers.

Both were retired teachers in spring 2022 when Bernardine unexpectedly turned up with Ayers at the 55th reunion of our University of Chicago Law School’s Class of 1967.

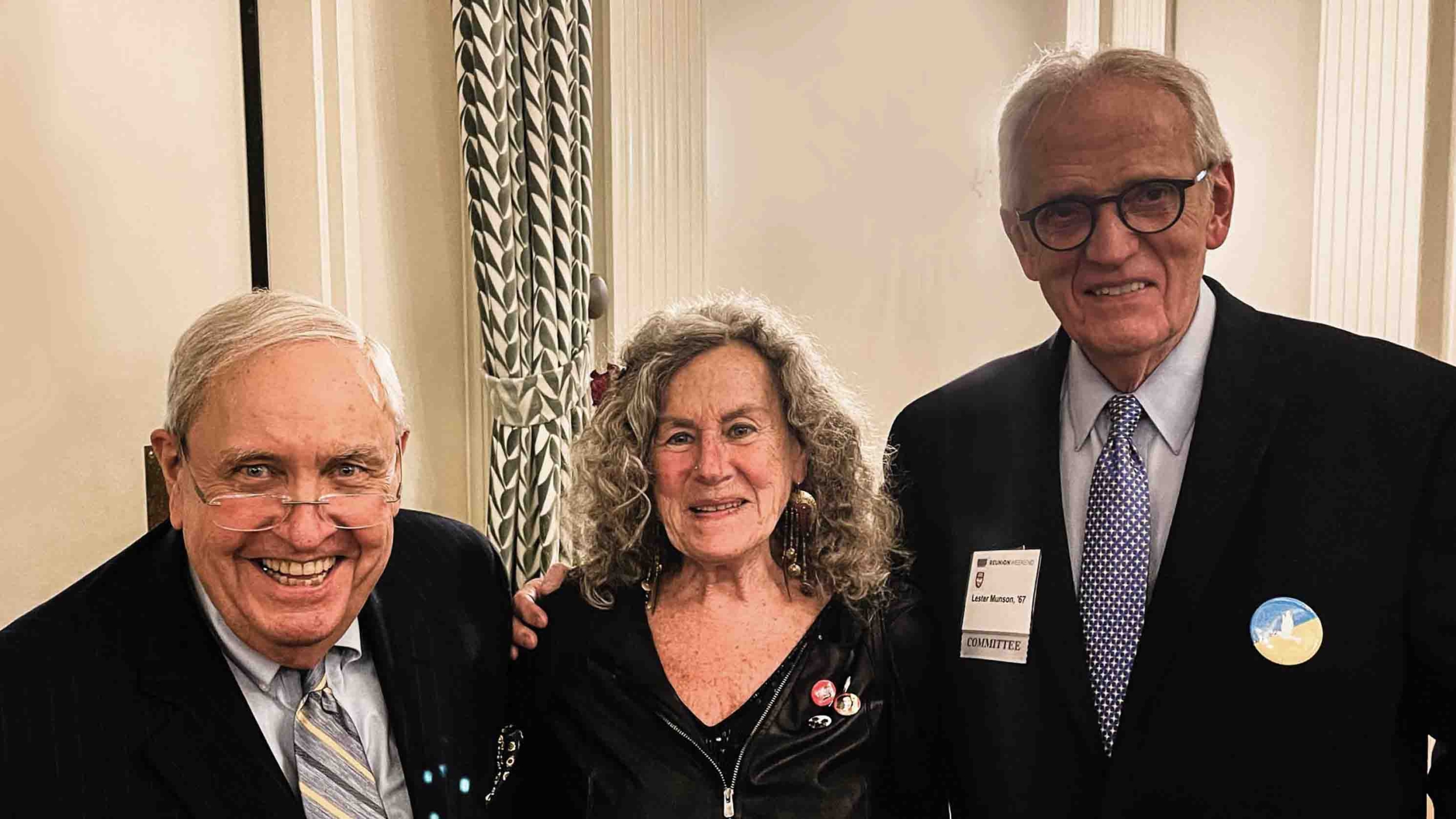

2022 Bill Bowe, Bernardine Dohrn and Lester Munson, Jr. at their 55th Law School Reunion

As the frequent emcee of these gatherings over the decades, it fell to me to introduce Bernardine as the main speaker. Bernardine talked about her career at Northwestern law school and then took questions from her classmates.

Still present in the answers to her classmates’ questions was the woman who saw white supremacy and racism as primary causes of her world’s ills.

However, for those classmates paying close attention, there was something new to be heard: hints of misgivings. In a late in life stab at self-abasement, Bernardine even allowed as how perhaps she might have done some things that weren’t “perfect.”

Arrogance and white supremacy?

“I’m saying we were part of the problem. I was, I think, by that arrogance, and by that sense that we could will our way into a changed society. But I also think that the depth and virulence of white supremacy is very much here right, right at our hands.”

Consequences and self-righteousness?

“I was so certain about some things that I forgot to stop and look at what the consequences were of what we were doing. I think we pulled back from the brink. We, you know, that part of the movement. But I think that the cost of self-righteousness is certainly high.”

Risky business and not exactly sorry?

“You know, I made the decision that waking up the American people about particularly the war in Vietnam … But I felt that the other piece about white supremacy wasn’t getting the same amount of attention. … So, we felt that that it was essential to kind of hurl ourselves into solidarity. I’m trying to think of the language that we used and what I felt at the time. And in a way, I’m not exactly sorry for that. I think that we were lucky. We tried to be very careful. We didn’t kill anyone, but what we did was dangerous. I don’t know what other word to use for it. We worked very hard to make it about property damage, and kind of a scream and wake-up to what was happening, but not to hurt anyone. And you know, I realized as an old lady how risky that was. And I don’t claim that it was even the perfect thing to do, just saying what we thought we were doing.”

It has been 60 years since Bernardine Dohrn and I entered the University of Chicago Law school in 1964. Most law school students by the time they graduate understand that one role of lawyers in society is to serve as conflict resolution professionals helping to work through human disagreements peacefully within a system of laws. In an unusual way after law school, Bernardine took the opposite path and became a prominent instigator of broadly based social violence aimed at destroying our democracy and replacing it with an authoritarian Marxist state.

In her answers to the questions of her reunion classmates, she couldn’t seem to bring herself even to clearly acknowledge that the bombing of Congress, and police stations was wrong. Bernardine explains in justification of her actions, that you had to understand there was a war going on she didn’t agree with, and “white supremacy” was afoot. The most she can say as to the error of her ways is that she doesn’t claim that what she did was “even the perfect thing.” She also goes so far as to say she participated in “risky business,” but “I’m not exactly sorry for that,” and “we didn’t kill anyone.”

In her middle and later years, Bernardine worked in a more productive way by engaging with young people involved in the criminal justice system. Fair enough, but for me it didn’t reset the scales in my opinion of her earlier political radicalism. I believe her life of violence in the 1960s and ‘70s badly damaged the country at the time, and that some of the scars of her excesses are present with us still.