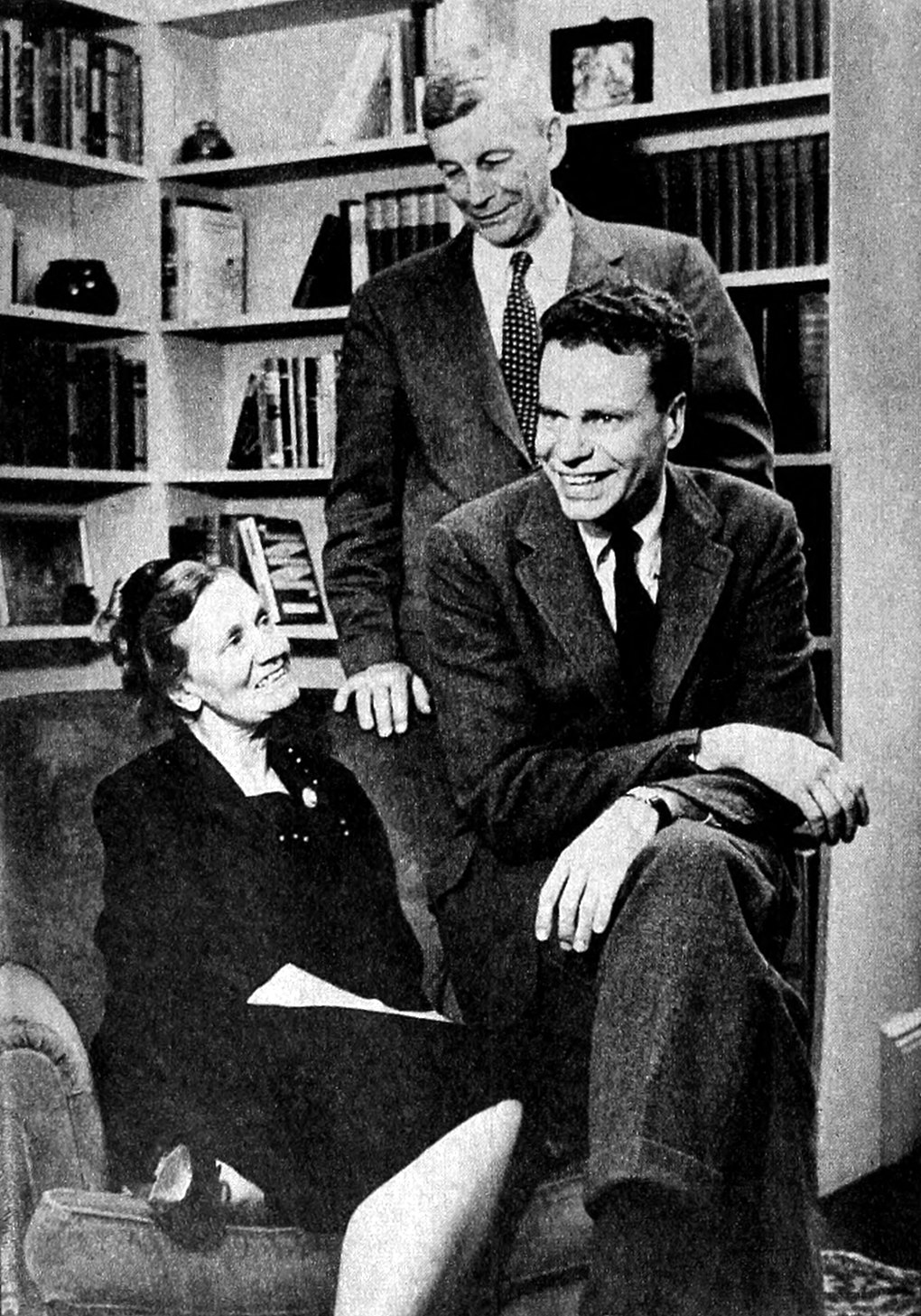

Editor’s Note: Shortly after the publication on Amazon of my memoir Riots & Rockets, Chicago Tribune columnist Rick Kogan asked me to join him in talking about the book on his WGN-720 AM radio show, After Hours with Rick Kogan. I have long admired Rick as he plays an important cultural role in Chicago similar to the pioneering example set by author and interviewer Studs Terkel.

Rick explored the book’s main themes in our conversation and then posted the audio recording on his WGN website with the “fascinating life” title. In retrospect, if I’d known it was going to be fascinating, I wouldn’t have slept a full third of it away.

Above you’ll find a video of the complete interview, together with English and French subtitles, chapters to help with navigation, and a searchable transcript. A full copy of my interview with Rick, together with some illustrations, is below. You can read or download a .pdf copy of the interview transcript here.

The Fascinating Life of Bill Bowe

After Hours with Rick Kogan

WGN-720 AM

Transcript of Rick Kogan Interview with Bill Bowe

5:00 p.m., Sunday, July 28, 2024

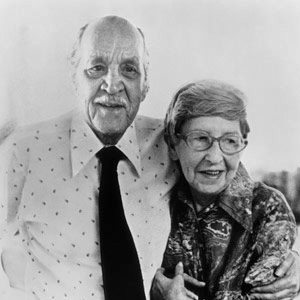

Bill Bowe & Rick Kogan

Introduction

Welcome to the latest edition of After Hours with Rick Kogan. This entire first hour is devoted to a friend of mine, but also a noted author with his first book. You had another book, Bill, but this one is your story. It’s titled Riots & Rockets, A dash of the army, A dose of politics, and A life in the law. Welcome.

Thank you very much. I appreciate it.

There’s so many things. We went to the same high school. You went to the University of Chicago. My father went to the University of Chicago. You were married to my great friend, your first wife Judy Royko. You spent a lot of time working politically in the 43rd Ward. That’s where I was born and raised. You went to Encyclopaedia Britannica, about which my father wrote the history. We kind of like brothers.

Like many people, you had retired and suddenly the pandemic arrives and you had some time on your hands. This book is one of the manifestations of that time, is it not?

It is. It begins, as not all stories do, with a terrible self-realization. I was becoming crabby early on in the lockdown and I thought in March of 2020, I thought this is just plain unfair to the dogs, and if it’s unfair to the dogs, it’s for sure unfair to my wife Cathy. At first, I thought the solution was to build a website. I had fooled around trying to learn how to build a website maybe 20 years before, very early on. I didn’t get very far, but I did register a simple name for the website back then that I kept. And so I got back at that.

What did you want to do that for? What did you want a website for?

Mostly photographs. I’ve taken photographs all my life and I had thought for many decades that eventually, at the way in which databases and computing was developing, it was certain that the images would someday be able to be stored and accessed electronically.

Of course, and we’ll get to all of this, when you worked for Encyclopaedia Britannica, you were really in on the early pioneering levels of what eventually became this vast world known as the internet.

Absolutely. Yes, my time there really overlapped with the era of what they call “Big Iron,” the big IBM mainframes that were needed in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, both in the university communities and in businesses. Of course, there were no personal computers until the early ’80s.

So how was it trying to start your website?

Well, I was delighted because the tools were better as I looked around. Important tools were free like WordPress. The underlying structure is a complicated piece of software, but it’s fairly easy to begin to get to get to know. So, the tools to actually do something are better And I discovered that I was able to upload all these family trees that my mother had created that I had digitized. She’d been a great genealogist. So, I got it all up on the website when a cousin said, “You know, this is terrific for the family, there’s so much stuff here, you ought to talk to somebody that can help you build a better website.”

So, you had done writing in your in your legal career. You’ve done a some— most lawyers do a lot of writing, but you’ve done some writing that was not legally based. You had done some writing during your life.

Yes, and I remember having one of the best periods of learning how to be a better writer. I recall when I took a leave of absence from my law firm to work on Bill Singer’s campaign against Richard J. Daley back in the ’70s, the fellow running the PR at the time for the campaign was a Channel 2 news reporter.

What is his name?

Don Ramsell

Don Ramsell.

Yes, I remember.

He’d been a street reporter for television Channel 2, and then he was editing. I was doing, position papers and speeches, and he was the only person around to edit it and make sure it was going out properly. And the grand lesson that he taught me with his red pencil was when he attacked and murdered lots of my adjectives. He was good at finding one word that could replace three other words. My learning was the skill to compress the writing and not be wordy. I got a great postgraduate, post school education from that television editor, because he was writing succinctly for the TV news.

So it certainly paid off when you decided build this website and after gathering all these pictures, you said, “Wait a minute. I may want to tell my own life story.”

When I ran out of family trees —and I have to give thanks to my mother’s work back in the ’50s and ’60s—I had 47 families that I pretty well covered.

Good Lord!

But when I ran out of the family trees, I was still kind of stuck in the lockdown that was still going on. I thought, “Well I’ve got a lot of pictures from my strange period in the Army ’68 to ’71. I’ll write just a short history or framework for that.” And once I just started that it just kept going and going and when I said, “Well that that does it.” I had about 12,000 words.

Wow! Yes, the book covers that period intensely and it gets into all the other periods and Bill Bowe’s fascinating life. The website he is talking about is wbowe.com. The book is titled Riots & Rockets. You can get it on Amazon. We will continue on. We barely touched on what you did. I mean the Army stuff is fascinating. Working for the MacArthurs is fascinating. Working for United Press is fascinating. Working in politics— you were in politics in one of the most vibrant, riotous periods in this city’s history. We’ll carry on after a short break.

Don Evans is the founder of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. He reviewed my guest Bill Bowe’s book. It’s William Bowe on the cover of the jacket. He’s Bill to me. Don has written:

“An intriguing tour of 20th century American history from a lawyer who by happenstance sat in the first row of our most harrowing dramas. Bowe seems to have been the Forrest Gump of the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and even on. He was a young intelligence officer during Vietnam. He was not spying on Viet Cong, but homegrown radicals like law school classmate Bernardine Dorhn. He then came into politics in his attempts to reform the machine. Then he was in on the demise of the United Press International’s wire service, the super-rich MacArthur family, and an invention of the internet.”

That’s a nice review. I know Don knows you, but yes, he’s right. about all this. You went to Latin school for high school. Where did you grow up, Bill?

I grew up on Elm Street on the Near North Side. Okay.

My parents lived there, and my father’s brother and his family also lived in the same building.

So a little compound. Yes, very good street and you went to Latin which was nearby at the time.

Yes. I’ve always been indebted to the school because I had a scholarship as I went through.

That’s great and it was a block or so away.

Yes, and I was close by.

Enlisting in the Army’s Intelligence Branch

Vietnam War Draft

Then you went to the University of Chicago for law school. Then where’s your… I’m trying to look… I’ve got… you should see this book. It’s got like a million notes here. When did you decide to join the Army if that’s the right word, it was at the height of the Vietnam War. Were you scared about getting drafted? I find that very interesting. Very few people I know– you’re a little older than I– but very few people I know said, “Hey, it’s 1968. I think I’ll join the Army.”

You’re right. It was the height of the War.

And the protests against the War.

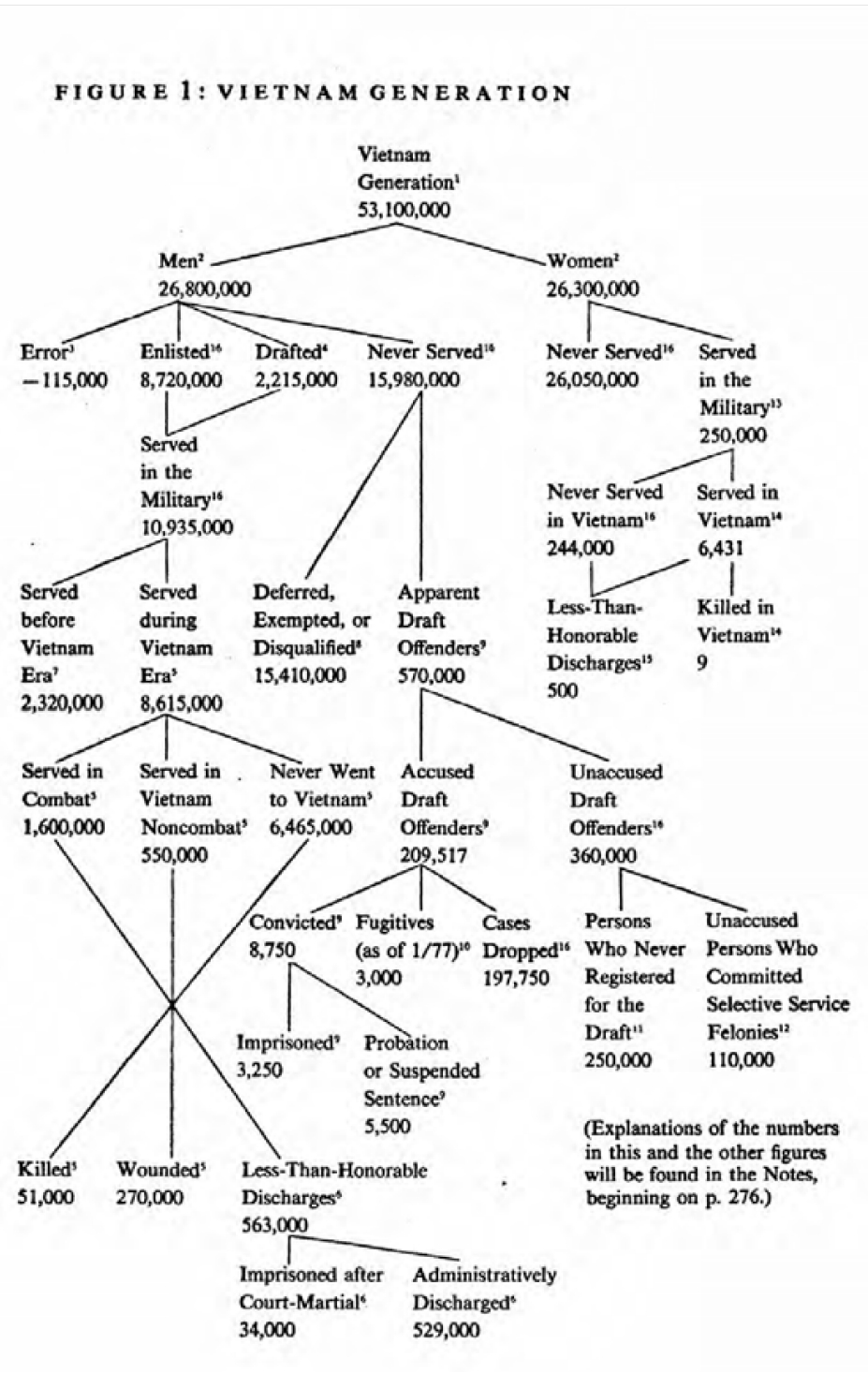

Yes, and they were picking up the steam shortly after I entered the Army after enlisting. The draft was one of the things that was uppermost on my mind. Women weren’t being drafted then, and this was pre-lottery, so I was at risk. But the problem was not just for me, but for everybody– this pool of draft age men was [about 27 million] over all the Vietnam years.

Wow!

That was the pool of males of the day that could be called. But the requirement to call wasn’t that close or remotely that close. There were only about two million, about ten percent of the [27] million, that were actually drafted. So how did it happen that they were the lucky ones that had a chance to lose their life?

The answer was, as you may remember, is that there was a whole series of complicated draft deferment categories. I found myself protected as a graduate student because the War really started when I was in the middle of law school. So they weren’t yanking you out, but I could have been drafted right after.

You grew up in a family where there was an older bunch of soldiers.

Yes, including a great-grandfather, father, brother and uncle. I was a late child, so my father was young enough to go to France in World War I. He was in the Illinois National Guard. He’d enlisted before the Great War I came along and went over with the doughboys. He lost part of his foot, so that amputation got him home after the War was over. He was in a hospital in France. It wasn’t enemy fire that did him in. He was trying to get on a troop train, and he slipped.

But also, one of the fascinating things is that later in his life his nurse from the War came to visit.

Yes, so here’s his nurse in Orleans, France who cared for him for about a year, and the healing was a terrible problem, very lengthy in those days. And she turned up as an old woman in Chicago and I met her. And my father had just died the year before she shows up. She’d missed him, but she’d come to Chicago to kind of get reacquainted.

So what did you expect when you enlisted. What did you expect to get out of the Army or to do in the Army?

Well, I thought I could go in as a lawyer. I was through law school and had a year of practice right before I enlisted. Because there was a war on, that was regarded as a safer choice. You could be a lawyer,r but you had to sign up for four years.

Right, right, right, right, right.

If you were drafted, you’d be in in for two years, but you might be in Vietnam. So that was not on my list of to-dos. I found kind of an intermediate choice. I enlisted for three years in the Army’s Intelligence Branch. I thought that was probably going to be more interesting, whatever it turns out to be, than the infantry or an artillery position. So that’s kind of what brought me in.

Civil Disturbance Planning & Operations Directorate

It did turn out to be interesting— being a word with a big umbrella under it. Talk about the “what” you did. What were you charged with doing, Bill?

Well, after basic training and the Army’s intelligence school at Fort Holabird in Baltimore, I got assigned late in 1968 to the 902nd Military Intelligence Group. This was part of the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence of the Army at the Pentagon. When I finally figured out where their offices were because it wasn’t obvious—

Yes, right, right, right because there wasn’t a big sign out front “Army Intelligence, Come On In.”

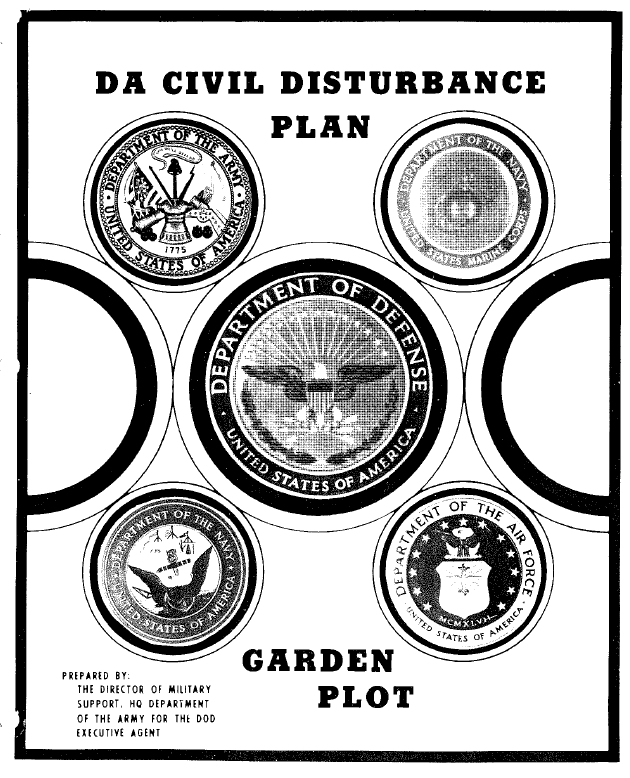

They needed a counterintelligence analyst to support the newly established Department of Defense joint service group called the Civil Disturbance Planning and Operations Directorate. The group arose from what they’d learned from the race disturbances in Detroit in ’67, and then Chicago. But after Detroit, the Secretary of the Army took a look at what happened in Detroit. The Army was not remotely prepared at that time for the domestic civil disturbance control mission where they’re getting involved because not only the local and state police, but also the state National Guards can’t control a situation.

Exactly.

And after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in April of ’68, suddenly the National Guards in Baltimore, Washington, Chicago were insufficient and federal troops, which is an extremely, historically an extremely rare intervention, came into Baltimore, Washington, Chicago all at the same time. So in the after-action report, the Army people responsible for the mission thought they’d better reorder their thinking in a big way, because this was a problem that was not going to go away.

I just happened to get there at the time this new organization was set up. They wanted a flexible organization that would only expand once there was a problem. So, you had a central group of managers at the Pentagon that I was assigned to support, DCDPO. The Pentagon has got more acronyms in it than any place else.

Did you enjoy your time?

Well, the work was absolutely fascinating because the job was. And this wasn’t the only thing I did. Most of the job, most of my time, was reading the internal security production of the day. The Army had its own problems. There were new draftees that were trying to organize unions in the Army, which the Army never thought was a very good idea. So, they were trying to keep track of that kind of thing internally in the organization. Mostly though it was external agencies, non-military agencies like the FBI and other federal agencies.

Were you happy to get out?

After three years, are you kidding? No, I was delighted. I was not ever cut out to be a lifer.

Leaving the Army, Bill Singer & Chicago Politics

Then what were your thoughts? “I’m getting out in like a month or two.” What did you want to do?

Well, I first thought I didn’t have to come back to Chicago where I’d started practicing. I thought, well, maybe I’ll go out to San Francisco. I’d seen that a little bit, thought that was a great place and interesting. And Washington DC was also interesting. But at the end of the day instead of coming back to the larger Chicago firm that I’d started with right after law school, a spinoff of it had given rise to a new smaller law firm. They asked me if I’d jump ship and join them. So I did.

You met Bill Singer in law school in your second year?

During law school, I met him because I was a summer clerk at the Ross, Hardies law firm, and he had been newly graduated from Columbia Law School. We had gotten to know each other then, and he was also one of the founding partners of the smaller firm that I joined when I got out of the Army.

And then he said to you, and we’ll carry on the political life, he then said, “Hey, I’m the Alderman of the 43rd Ward. I think I’m gonna run for mayor!” I remember that vividly, and you joined the campaign full-time.

Yes. He asked me if I take a leave of absence from the law firm and be the General Counsel of his mayoral campaign. Also, he needed a Director of Research for the campaign for the policy work.

Did you think he had a chance?

I certainly hoped he did, though I don’t think I had stars in my eyes that this was some easy task.

Yes, because he was running against Richard J. Daley.

That’s right. Now what’s interesting is that the way that election turned out was very different from the norm. Usually, Daley could run up vote totals in the Democratic primary from 70 percent to the low 80s. But that year that Singer and a couple of others ran against him there was a shocking comedown. He only got 55% of the Democratic primary vote. He didn’t even get a majority of the Black vote, which was the first time that had happened ever.

I jokingly like to think that as a result of my hard work in that campaign I was able to hold Singer’s vote total to under 30 percent.

You also got to meet the one and only Don Rose. We will continue on.

With Bill Bowe once again, the website is wbowe.com and you can buy his book titled Riots & Rockets. We’ve only touched on some of the things that Bill has done in his remarkable life. Go to amazon.com, and you’ll find it there. After the news, we’ll be back.

Welcome back. We’re continuing our conversation with Bill Bowe, the author of Riots & Rockets. It is intensely, I know it goes a little far, afield, but it’s an intensely wonderful recollection of a time in Chicago — some very raucous life altering times.

When you wrote this book Bill,— it’s so wonderfully detailed— I’m looking at one page: I see Don Rose, Basil Talbot, Mike Royko, Ron Dorfman and a bunch of other people. Did you trust your memory when writing this book?

Absolutely not.

Because I’m stunned by the detail and love the detail.

The detail is a genetic advantage I have. My mother was a packrat. In her lifetime, she kept track of all the paper she ever ran across and was highly organized. She wrote late in her life as a widow a lengthy genealogy of her husband’s family and her own family. I watched her do this and the paper that she had that she’d been carrying around forever in files. I think that’s the gene that I caught.

When I retired, I’d been carting around with me a couple of file cabinets. So, when I retired, I started going through it. Of course, when you throw stuff out, you wonder why you’d carried it around for a lifetime in the first place. But the nuggets that were left really permitted me to do the research for the book.

Did you ever sit back and say to yourself, Good Lord, I’ve had an interesting life!

Well, I think maybe once I retired. Also, when the lockdown came, I began thinking at first about what I didn’t write when I got out of the Army. I thought I’d write a book at that time, but it wasn’t in me back then.

But at this time, I thought I should write about the Army. That was just fantastic, in a weird way, particularly the whole part of that experience which had nothing to do with civil disturbances, anti-war demonstrations and riots. It had to do with really the dawn of the Space Age. Just barely a decade after Sputnik in 1969 the Army sends me out to Kwajalein Atoll in the far western Pacific, South Central Pacific out west of Hawaii, to do a study on the espionage and sabotage threats to the anti-ballistic missile system.

Wow!

There was that part of the Army experience, too. So when I sat down to write kind of a short account of my Army days, it quickly grew to 12,000 words. When that finished, the lockdown was still going on. I thought, well now, what else did I see in my life that was a little bit interesting.

It’s just so striking and stunning to me. You do a really wonderful job when you’re back in Chicago with Bill you were in one of the most exciting and crazy times in the newspaper business here, too.

Absolutely, absolutely.

Rod MacArthur & the MacArthur Foundation’s Genius Grants

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

How did the MacArthurs come into your life?

I was practicing law most of the ’70s after the Army and there was a lawyer at the firm one day who said, “You know, I was talking to one of my former law professors at Northwestern and he said that he knows someone who’s looking for a general counsel of their company. I was doing that kind of work in a private law practice for companies mostly, so I looked into it. It turned out to be the Bradford Exchange. It was owned by the son of John D. MacArthur and the company had had its origins in the senior MacArthur’s enormous Bankers Life and Casually Company insurance combine. John D. MacArthur had built the business into an enormous behemoth that ultimately was sold. The billions of dollars from MacArthur’s estate went primarily to the MacArthur Foundation.

Did you like the MacArthur’s? I’ve heard many many things about that.

Well, I never knew the father who died I think in [1978]. By all accounts he was cantankerous and foul-mouthed.

Like many Chicago millionaires.

And he had a very rotten relationship with his son Rod. who was my client. Roderick MacArthur was John MacArthur’s only son. Rod had worked for his father through to middle age and for him it was just elder abuse — by the elder of the youngin.

You weren’t there when they started these so-called genius grants, were you?

Yes, and in fact, this was one of the great contributions that Rod made. Although he was spending most of his time when I was working for him fighting with his fellow directors on the new MacArthur Foundation. But where he really contributed in a completely positive way was in being the lead director really to root for and figure out the details of what became their Fellows Program. But the media has called it always the genius grants

That happened right away. And I remember everybody who wanted one of those things and still do I suppose. Bill Bowe, you have a wonderful personality. You seem to have gotten along with a wide variety of people. Did you, do you give yourself credit for that?

I suppose I was just brought up that way —put your hand out and shake somebody’s hand. Put your hand out there first and be honest. In a law practice, you’re really trading on your judgment and good sense. I always looked at practicing law as applying highly refined common sense.

United Press International

UPI Teletype Machine

Interesting, interesting. Talk to me about United Press International. That’s another chapter ladies and gentlemen.

Well, UPI was founded in 1907 as a competitor to the Associated Press. Early in the last century, there was a terrible problem for the news business. The people that were running newspapers were hiring reporters locally. It was a city by city basis. There weren’t many newspaper owners at that time that could afford to have reporters in a faraway city like Washington.

Like our Colonel Robert R. McCormick, like the Tribune.

Exactly. These individual paper owners created a cooperative called the Associated Press. It hired reporters all over the country. They had one basic rule though. All this news from all over the country, the feed of the AP wire service and then later the world, could only go to a single paper that was a member of the AP in any given city. So, the UPI got started by E.W. Scripps in Cincinnati to compete with AP.

You know, this is a time ladies and gentlemen when many cities in this in this country had more than one paper.

Yes, the olden days.

We still have two here. What was that like with a couple of idiots running UPI.

Scripps had owned UPI throughout most of the 20th century, but by the 1970s the newswire service was losing money. The heirs of Scripps said, “Hey get rid of this thing. You know, cash out, cash out.” And there were legal liabilities if they continued to lose money like that. So, they tried to sell it to NPR radio and to CBS, but none of the logical media buyers wanted to buy a second banana wire service. Finally, they were so desperate to sell, they sold it to two young Nashville entrepreneurs. They’d made a little bit of money by getting some FCC television licenses for low-power television stations, and they suddenly popped up and said, “We’ll buy it.” Of course, they didn’t have enough money to actually run the business, and they didn’t know what they were doing. Scripps was so desperate to unload it, they sold it for a dollar. And then Scripps also put in about $5 million of operating capital and said, “Good luck.”

Internet Disruption of Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Newspaper Industry

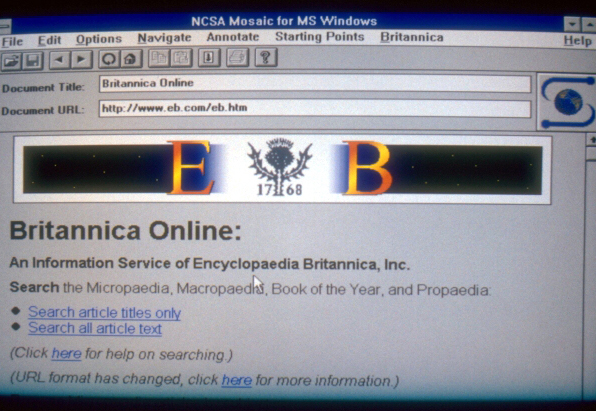

1994 Britannica Online

That is desperate to sell. That is desperate to sell. Did you around that time, did you sense what has happened to newspapers. It would be impossible to have known that.

Well, Yes, and no. What I remember very vividly particularly in the in the ‘90s, when the internet was beginning to get started, an early victim if you will, forced into a transformation was Encyclopaedia Britannica, where I was Executive Vice Present and General Counsel. It was buffeted wildly from a financial standpoint, and indeed Britannica changed ownership as a result in the mid-’90s. At the time, the newspaper industry hadn’t at all been touched by the internet in that way. Reporters in the industry looked askance at a victim of the new internet like Encyclopaedia Britannica, which is an odd survivor today. More than surviving, Britannica is thriving today over the internet.

That’s amazing. I want to talk about that.

In any event the newspapers didn’t realize the internet was coming after them too. I had been going through it earlier, seeing the great shock to a company when you’re being displaced by a major technological change, a true secular change in the business environment. It’s going to just upend anything and everything. Now, we often think about artificial intelligence as perhaps having the same effect.

Yes. When we come back after a short little break, we will finish off this hour with Bill Bowe. Again, the book is titled Riots & Rockets. You can go to Bill’s website, which is fabulous. Want to see pictures? Go to Bill’s website to wbowe.com, wbowe.com. We’ll be back in a couple minutes to talk to Bill about Britannica, which he says is thriving now. Yes. It’s amazing, amazing, amazing. We’ll be back.

The Writing of Riots & Rockets

Bill Bowe has been on this since five o’clock talking about his life and his book. His life is really captured in vivid, vivid pages in his book Riots & Rockets. His website which you can visit is wbowe.com, and you can go to Amazon to buy his book.

It goes far afield from Chicago here and there, but basically, I like to think of this as a real Chicago centric book. You must be pleased with it, Bill Bowe. It’s an accomplishment to write a book and it’s a different kind of a compliment to write a book about yourself.

Yes. Actually, one of the things that was concerning me a little bit was that I had these five stories that were, for me at least, very interesting. They all were historically important in some respects, or they spoke to some larger historical development. I’d been exposed to them only because it was the nature of my work. I was in the middle of these events. When I started my research and writing, I wanted to be able to make sure the historical context was rich and full, well beyond what was my immediate experience. I didn’t want to write something boring. And to me, almost by definition, that is the greatest danger in any lawyer’s memoir.

Yes, it would tend to be.

Not that I wouldn’t read an autobiography of John Marshall, but I think that my concern helped produce a book more about these events and times than about me. I think a better, larger picture of the period has resulted.

I do too. Your wife of many years, Cathy, was she your first reader or did she did she care about this before you finished it?

I was mostly sequestered throughout in my office. I was not handing out drafts along the way. It was just really grinding away with the research and filling in the historical gaps.

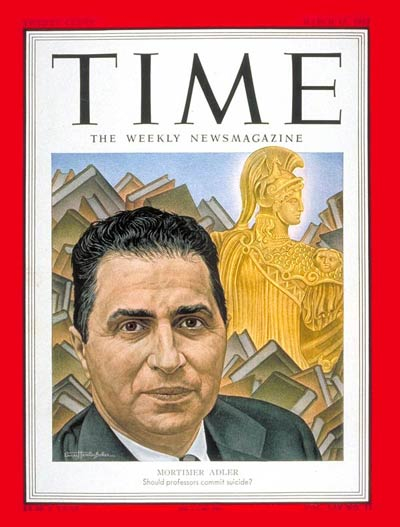

Charles Van Doren, Encyclopaedia Britannica & Aristotle on Happiness

Dorothy, Mark & Charles Van Doren

1952 Mortimer Adler on the Cover of Time

Seeing your life and putting your own life between covers can be very, I think a very, very empowering thing. Was it for you?

Yes. To be able to have the time and the concentration to go back over your life and look at it in detail, you have to revisit moments that aren’t so happy as well as look at the good times.

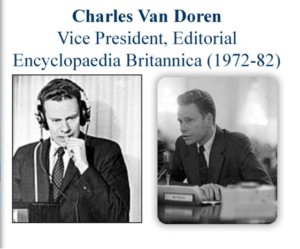

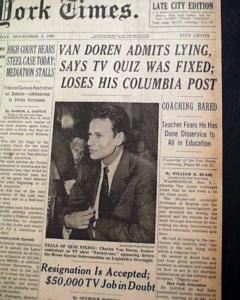

I got to Britannica a little bit after Charles Van Doren. In the late ’50s, he was the most notable figure involved in the television quiz show scandals. He was fed answers to questions ahead of time without the public knowing it. He later had to admit all of this before Congress in later hearings. If you remember, after winning big, he was on NBC on its nationally televised Today program. He was a big star. So here he was a college professor, an English professor at Columbia, son of a distinguished poet, and here he becomes this national pariah. It kills his career in academe, to say nothing of his new television career. Shortly afterwards, he goes to work for Encyclopedia Britannica. When he got to Britannica, he was helping to write books that Britannica commissioned.

In answer to your question about taking a look back at your life, I think of Van Doren. As a young man, he had to live the rest of his life with this cloud that followed him wherever he went.

Before the scandal, he had taught English at Columbia University. Late in life, a class that he had taught asked him to come back and speak to them at their 40th Class Reunion. This is in the book and it’s quite poignant. He asks them if they remember reading with him 40 years before about Aristotle’s idea of happiness. He says, “In case you’ve forgotten…”, and goes on to quote Aristotle to the effect that it’s really at the end of a life when you look back that you can find true happiness. It’s not some fleeting moment of pleasure or a feel-good instant. It’s at the end of a life and being able to look back and feel this emotion. And when Van Doren concludes this remarks that I was paraphrasing, he says, “It makes sense, doesn’t it.”

So, here he is talking to his class of former students, all of them, like everybody else, must know how difficult it is for him to allude this way to his checkered life.

It’s kind of haunting. Yes, kind of haunting.

I met him once when he came back for Mortimer Adler’s funeral at St. Chrysostom’s on the Near North Side. In his remarks, he really described Adler very well. I went up and chatted with him afterwards. I told him what a good job he’d done capturing Adler. He had said that when he’d fallen in the mud, Mortimer Adler had picked him up, brushed him off and gave him a job at Britannica writing books, a job that you’d enjoy even if you weren’t being paid for it.

He was quite a quite a figure and I had recently been doing work on a project he had started involving a Greek translation of the Britannica. When I talked to him about it, he got a big smile. He was remembering his past and you could see that the several decades he spent with Britannica out of the limelight was really what gave him the chance to say in effect, “I’ve had a happy life.”

What do you say?

I’d say I’ve made it, and I’m not done with it either.

Afterthoughts

Exactly. Do you think you might have another book, because there are parts of this book where you might have— not an 800-page book like Barbara Streisand’s biography— but where you could have expanded. You could write a book I think only about local Chicago politics.

Yes, and what a fascinating subject, no question. The part of my book that deals with the ’70s and the ’80s of Chicago politics, that was such— that whet my appetite. It was so much fun to be involved in politics in that period. It was a crazy period, and we had a full range of magnificent personalities. Jane Byrne, Jay McMullen, and others.

Bill, it’s a wonderful book and it’s a wonderful read and you’re a good, fine, fine writer. Don Evans is right about everything he said. Again, ladies and gentlemen, the complete title of the book is Riots & Rockets, A dash of the Army, A dose of politics, and A life in the law. It’s very, very focused on Chicago, but travels all over the place. It’s dedicated to your wife and kids.

And my genealogy loving mother.

That’s right, genealogy loving mom. Bill, great success with this.

You can get it on Amazon easily, and write another one, Bill. All right. We’ll be back after the news.

[The transcript has been edited for clarity.]