C. David Anderson with Classmate Roberta Ramo at their 50th Law School Reunion

Editor’s Note: David Anderson was one of several members of the Class of 1967 at the University of Chicago Law School who also was a college classmate of mine. After our 55th Law School Reunion, David wrote me about his Air Force tour of duty as a lawyer and what some other University of Chicago Law School graduates did as military lawyers after graduation. It turns out none of them were bored.

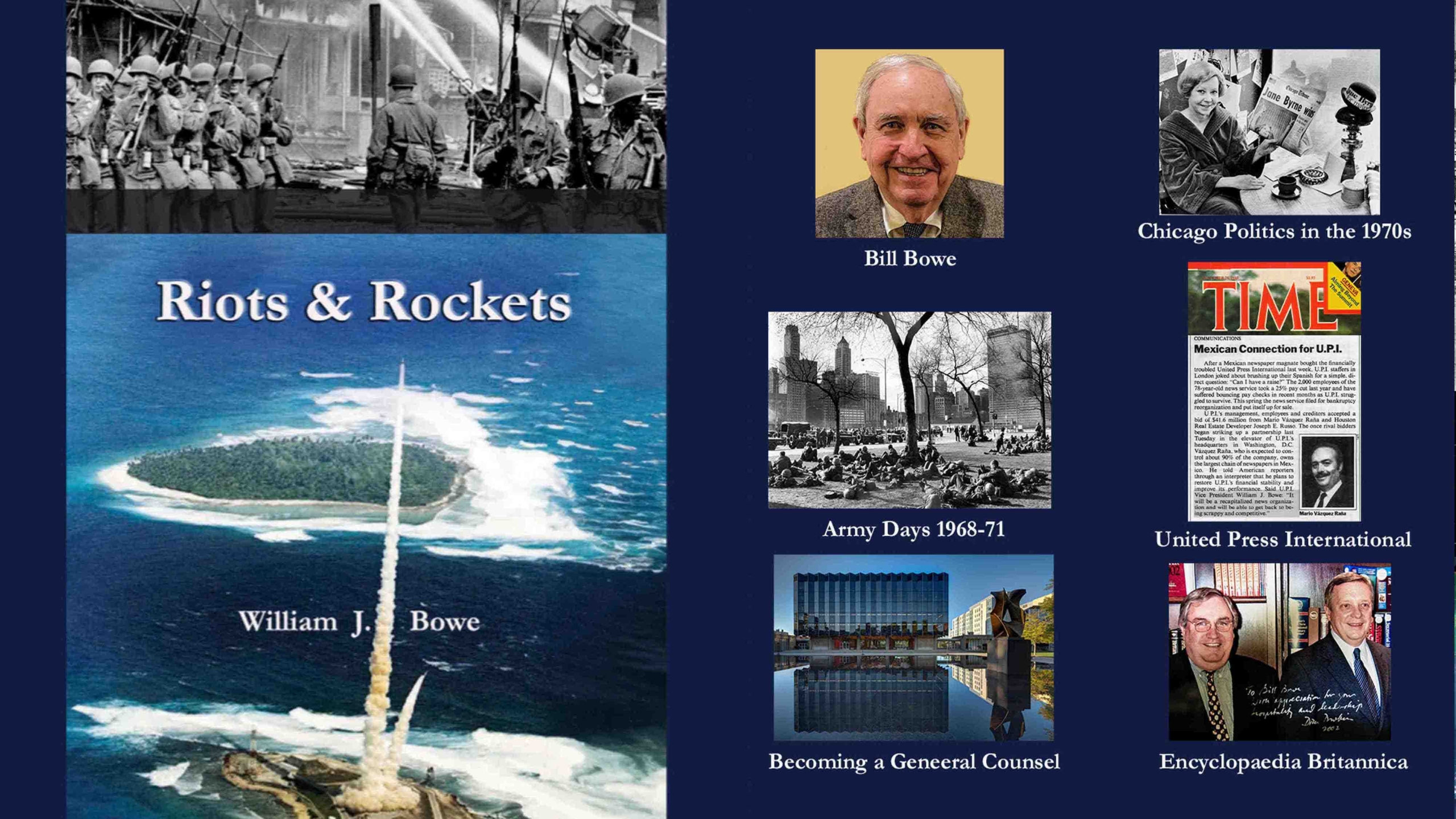

Bill —

The pictures in the 7-minute Reunion video were wonderful, and I very much enjoyed your stories about your time in the Army. I really look forward to seeing the video you made at the presentation by Bernadine and others at the Reunion last week.

I had a military experience whose beginning was quite similar to yours. I was 23 when I graduated from the law school, and thus faced a more than two-year exposure to the draft. Soia [Mentschikoff, a University of Chicago Law School professor. She had earlier been Harvard’s first woman law professor, and late became Dean of the University of Miami Law School] had wonderfully arranged a clerkship for me on the Second Circuit for the fall of 1967 which I had accepted. But on a whim I had earlier applied for one of the two military slots in the Air Force General Counsel’s office despite having no chance of getting it. Then my sister died at Christmas 1966, with me acting as the night nurse for nearly a month. Horrible experience, leaving me devastated.

Not wanting to be in the Army, and not wanting to expose my parents to the loss of another child, I started talking to my draft board about how they would treat a clerk for Judge Waterman on the Second Circuit. The guy I was able to get in touch with at the draft board kept saying “Out-of-state you say?” “You say this judge is in New York?” “Not a Wisconsin judge?” I got the picture that federal appellate clerkships might not be a viable path, and anyway, even if I got a follow-on Supreme Court clerkship, I would still have been 25 at the end of the 2nd clerkship.

Then to my amazement, in January I actually got accepted for a direct commission in the Air Force, with a three-year assignment in the Pentagon! Judge Waterman was very understanding, and also didn’t want to risk having a clerk drafted away in the middle of the clerkship. So I decided I could accept the Air Force appointment.

Several months later, my draft board contacted me officially, making clear that they were putting me in process to get drafted. I called the draft board and said “But I’m going in the Air Force!” They replied “Good, if you get in the Air Force before we get you in the Army, then you’ll be in the Air Force. Otherwise, you’ll be in the Army.” This was significant, because I had to actually be admitted to the bar to be sworn into the Air Force. Fortunately, Wisconsin had a system which allowed you to take the bar exam starting on Tuesday, and you would find out by Thursday afternoon whether you passed, and could be sworn in the next day!

So when I got an order to report for Army induction in early August, I had the great pleasure of writing a letter to my draft board on Secretary of the Air Force letterhead, declining induction, and signing it “First Lieut. USAF(R), serial number FV3199842.”

Tom Morgan (Class of ’65) was also in our Air Force office, and we had a great time working together on the F-111 Mk II avionics contract, a complete mess.

Seeing that you worked on civil disturbances in the Washington area, you might remember or have been part of the official reaction to the March on the Pentagon. I happen to remember it clearly because it was on a Saturday and I was coming into the office dressed as usual in my civilian clothes. I decided to take a walk around the Pentagon, walking outside the line of airborne troopers stationed there with fixed bayonets, backed by young lieutenants who looked at me with angry eyes. I was clutching my Pentagon pass and Captain’s identification in my pocket, but it was a spooky moment. and I didn’t want to have to see if I could pull rank on the young lieutenant.

By the way, your efforts to get into the JAG might have led to a rewarding experience. My roommate Frank Wohl from the class of ’66 was quite antiwar, but joined the Navy JAG and volunteered for Vietnam because he wanted to find out what was really going on over there. He did a lot of trial work in the first Marine division, which involved flying out to remote bases for interviews and trials, and taking some considerable risks doing so. He really found the experience rewarding however, and perhaps that led to his distinguished subsequent 10 year career as a prosecutor in the Southern District.

Three other Pentagon oddities — when I got to SAF-GC, the older guys told me that the officers in the best part of the Air Staff, “Plans & Operations”, were quite strongly anti-war by 1966. It turns out the Air Force fights with officers, their friends were rolling in hot on dirt trails in Laos, and getting killed in the process. And these hotshot pilots in Plans & Operations – where you had to get your ticket punched if you wanted a star – had seen the North Vietnamese repair the trails overnight — and really didn’t think bombing dirt trails was doing any good. Hence, they were antiwar. But, they were fairly quickly told to shut up, and as a result I didn’t hear anything like that from Air Staff while I was in the Pentagon.

What I did hear directly was from a girlfriend who worked for IBM, and compiled the statistical reports for the Strategic Hamlet program from the data sent from Vietnam. She said that when you were watching the numbers every week it quickly became obvious that the numbers were fake – completely unchanging for weeks, and then, when some report had to be made, magically amended to support whatever conclusion the report needed. This was in ’67 and ’68.

Third — While I was in SAF-GC, Frank ZImring was the staff director of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. He asked me to write a summary of the Army Civilian Marksmanship Program. This program was being held up by the NRA as an example of the fact that civilians needed gun training, so they could better satisfy Army requirements for soldiers to be able to shoot straight. Frank wanted me particularly to work on this, because I had a top-secret clearance, and the Army couldn’t stop me from looking at their records by claiming that the records were “secret.” The interesting conclusion which came out of the study was that the Army cared so little about marksmanship that they ignored basic training marksmanship results in assigning people to military specialties that required marksmanship, like “infantry.”

As we frequently remarked, the Pentagon was a Puzzle Palace.

Thanks again for the pictures, and I hope to see you soon.

C. David Anderson

May 16, 2022