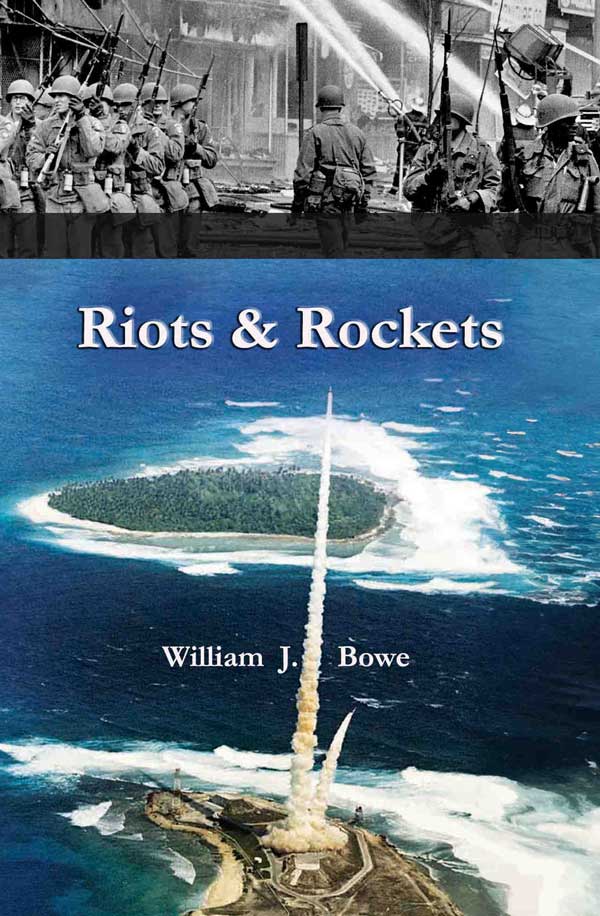

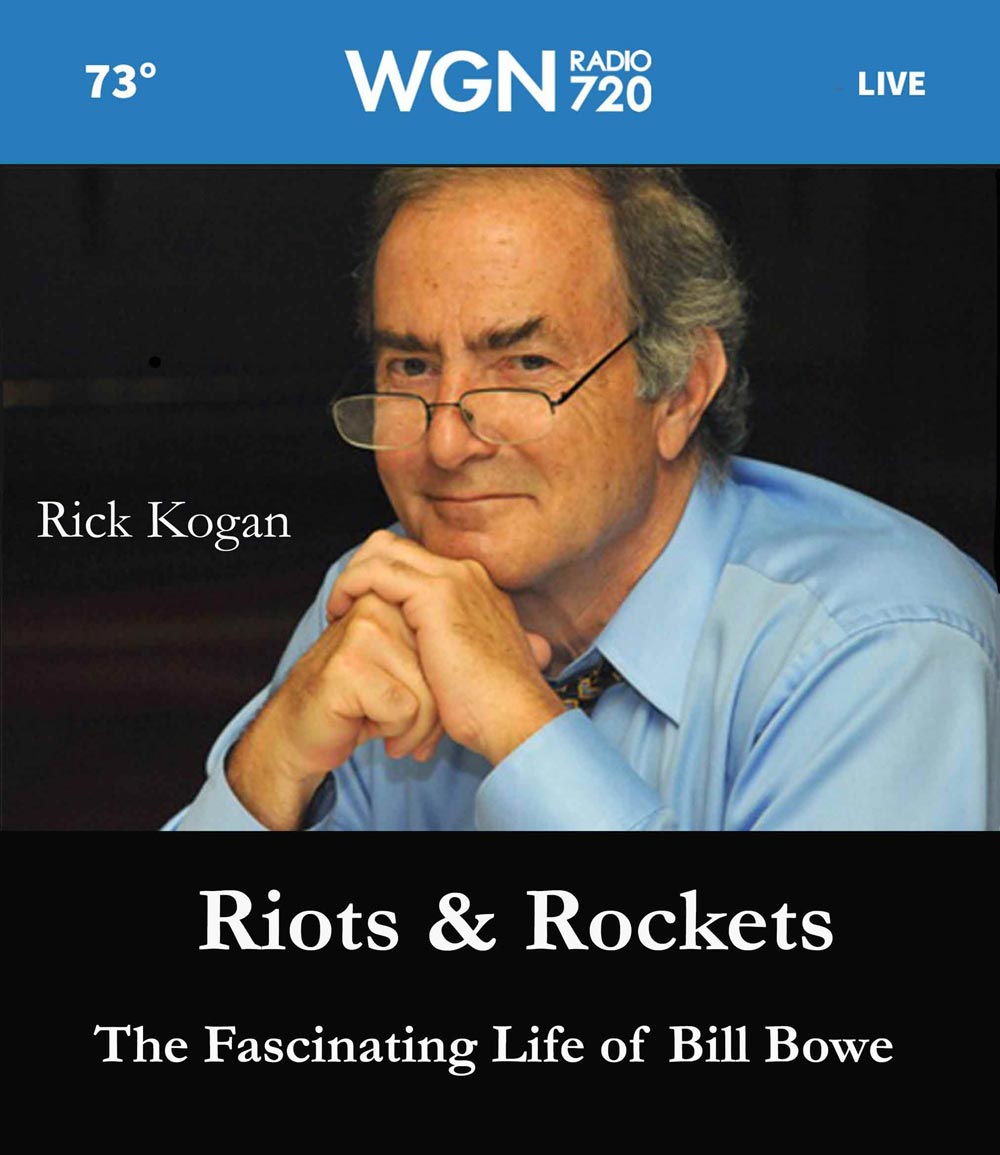

For more than a half century, William Bowe’s legal career took him to places and situations of enormous historical and cultural magnitude. His access as a military then corporate lawyer with expertise in counterintelligence then intellectual property meant he knew these stories, inside and out. Bill tells these stories in his fascinating memoir, “Riots and Rockets: A Dash of the Army, A Dose of Politics, and A Life in the Law.” Bill expertly documents and explores major events, movements, and people, drawing out the history in vivid, precise prose. Throughout this memoir, the author amplifies our understanding of particular moments, such as intellectual property rights in the new internet age, while entertaining us with insider observations. Bill is more participant than bystander in many of these stories, but his style, underscored with humility, beckons us to view our past in clearer terms.

A Lawyer in the Vortex

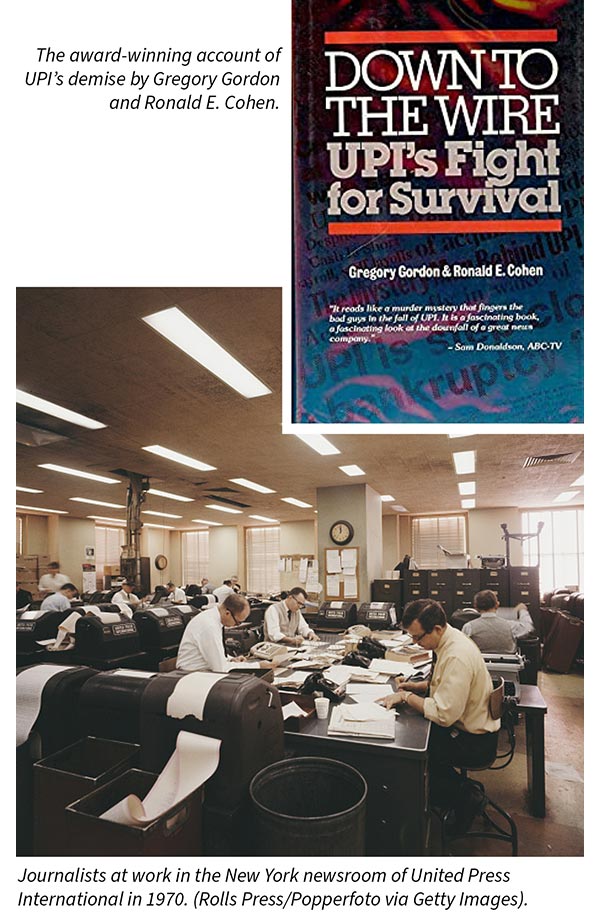

Rockets & Riots is a testament as to how lawyers find themselves in the vortex of events that define an era. As a recent law school grad in counterintelligence, William Bowe helped to deal with the scary business of both rockets and civil disorder. In Chicago, he labored to elect a new mayor who opposed the reigning machine politics. He saw one media giant, the UPI, collapse as times and ownership changed, while another, Encyclopaedia Britannica, remade itself with innovations that pointed to the digital future. The management of change and the control of intellectual property were his stock in trade. We can be grateful for these fascinating reflections.5.0 out of 5 stars

A Remarkable Story of Events that Shaped Contemporary America

Riots & Rockets is an entertaining and intriguing exploration of critical events that helped shape the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. It further enters the fascinating world of Chicago politics and offers a provocative look at the early developments of information technology.5.0 out of 5 stars

For more than a half century, William Bowe’s legal career took him to places and situations of enormous historical and cultural magnitude. His access as a military then corporate lawyer with expertise in counterintelligence then intellectual property meant he knew these stories, inside and out. Bill tells these stories in his fascinating memoir, “Riots and Rockets: A Dash of the Army, A Dose of Politics, and A Life in the Law.” Bill expertly documents and explores major events, movements, and people, drawing out the history in vivid, precise prose. Throughout this memoir, the author amplifies our understanding of particular moments, such as intellectual property rights in the new internet age, while entertaining us with insider observations. Bill is more participant than bystander in many of these stories, but his style, underscored with humility, beckons us to view our past in clearer terms.

A Lawyer in the Vortex

Rockets & Riots is a testament as to how lawyers find themselves in the vortex of events that define an era. As a recent law school grad in counterintelligence, William Bowe helped to deal with the scary business of both rockets and civil disorder. In Chicago, he labored to elect a new mayor who opposed the reigning machine politics. He saw one media giant, the UPI, collapse as times and ownership changed, while another, Encyclopaedia Britannica, remade itself with innovations that pointed to the digital future. The management of change and the control of intellectual property were his stock in trade. We can be grateful for these fascinating reflections.5.0 out of 5 stars

A Remarkable Story of Events that Shaped Contemporary America

Riots & Rockets is an entertaining and intriguing exploration of critical events that helped shape the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. It further enters the fascinating world of Chicago politics and offers a provocative look at the early developments of information technology.5.0 out of 5 stars

Author’s Note

“In early 2020, I feared my increased irritability during the ensuing lockdown could be a telltale sign I was descending rapidly into curmudgeonhood. Thinking this would be unfair to the dogs, not to mention my wife, Cathy, I decided I needed a project to keep my head straight. I started thinking and writing about several of the strange periods I had lived through in the years since my graduation from law school in 1967."

Shortly after the publication on Amazon of my memoir Riots & Rockets, the distinguished Chicago Tribune columnist Rick Kogan asked me to join him in talking about the book on his WGN-720 AM radio show.

About Riots & Rockets

About Riots & Rockets

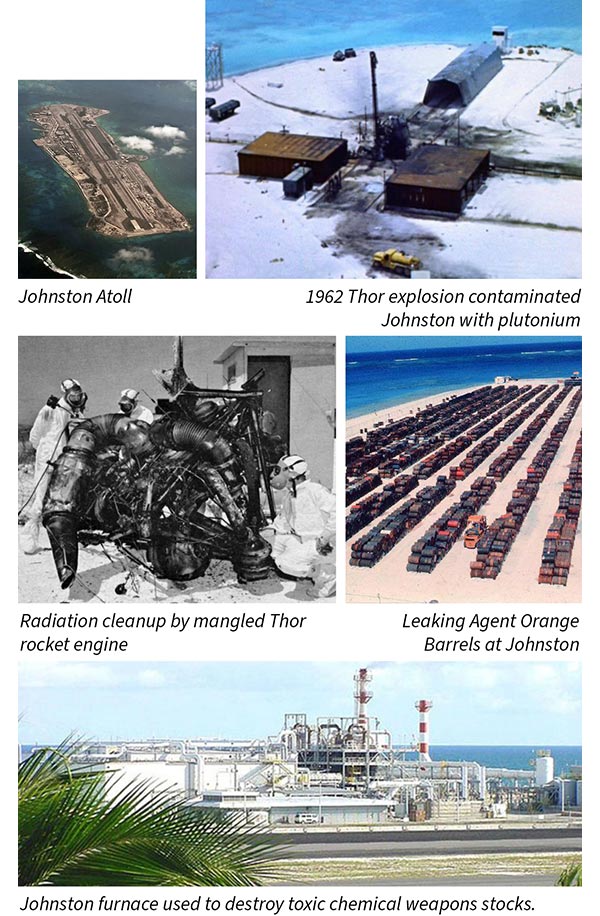

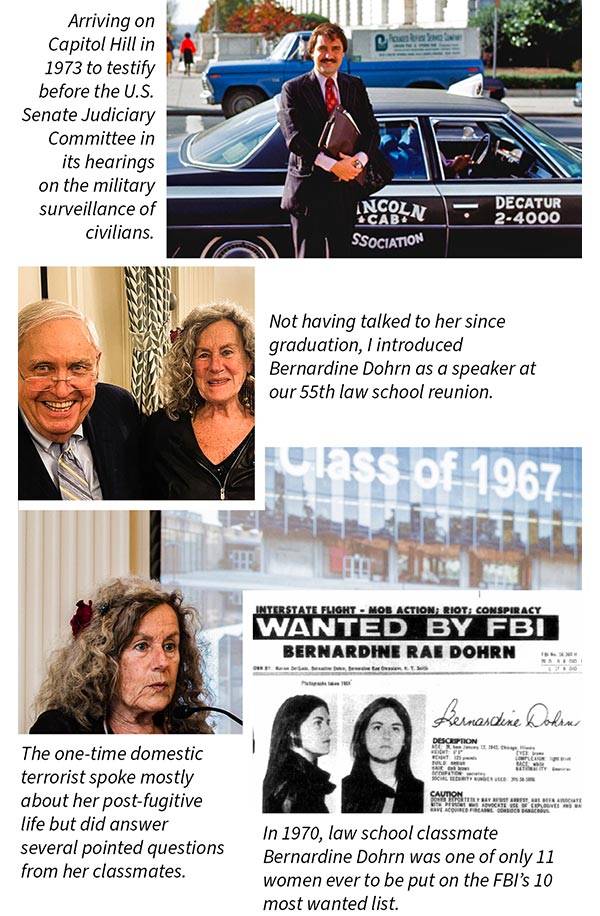

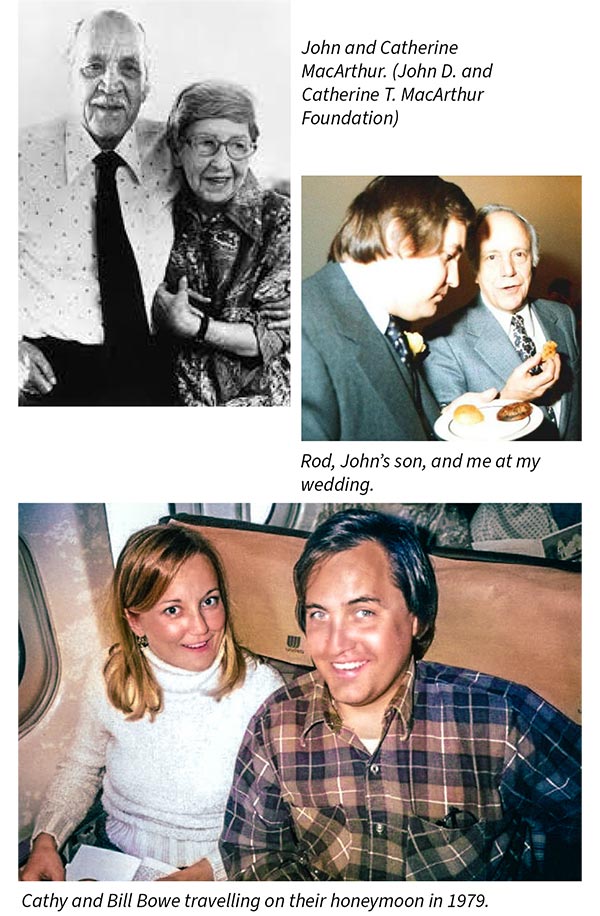

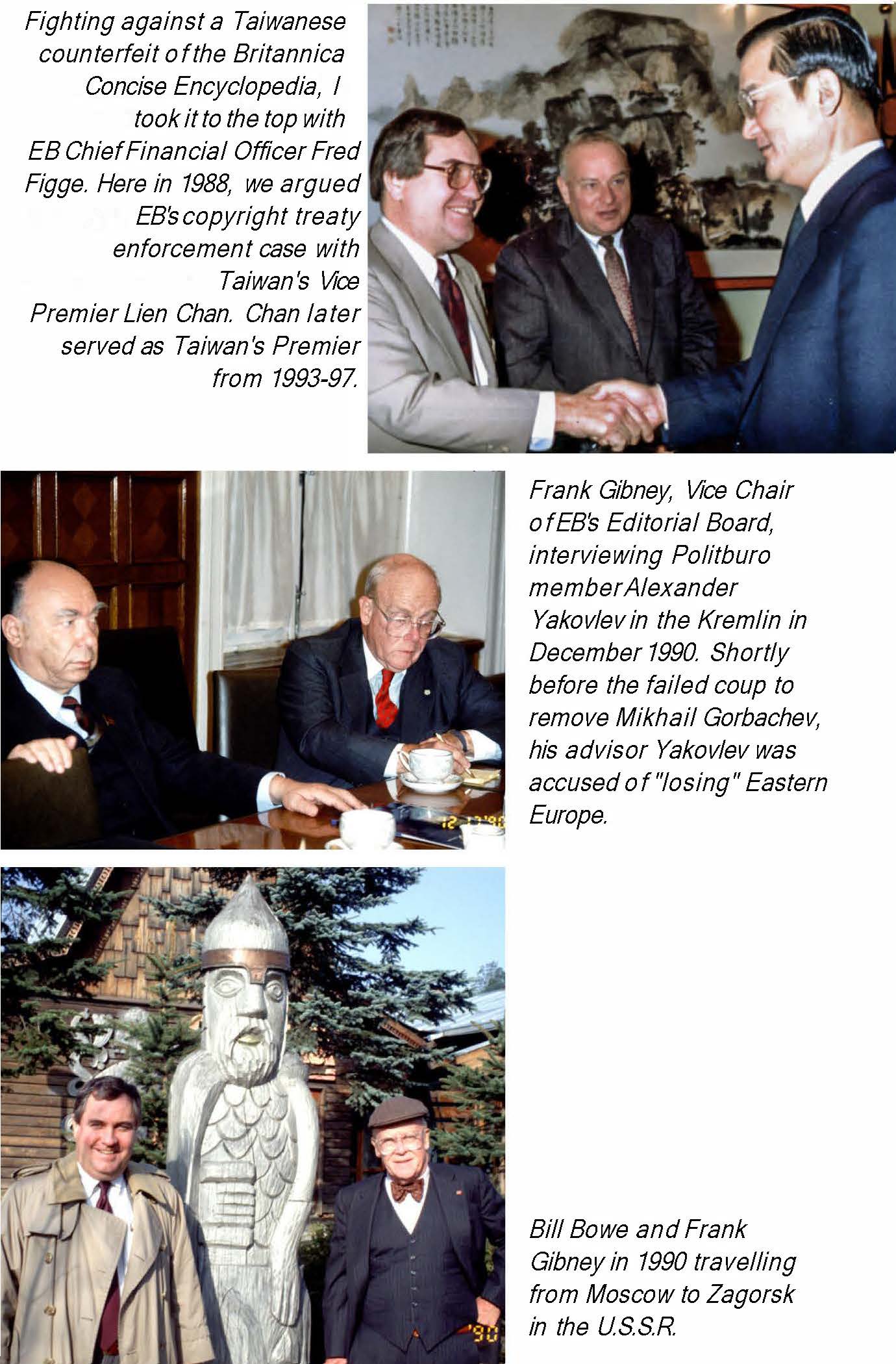

After retiring from a long career as Encyclopaedia Britannica’s Executive Vice President and General Counsel, William J. Bowe started thinking and writing about several of the strange periods he lived and worked through in the years since his graduation from law school. While the five stories in this collection are very different from one another, together they all tend to reflect some of the larger historical forces that define their periods. The title of the book Riots & Rockets is taken from the first story and comes from the Vietnam War era. During that fraught time, while cities burned amid racial unrest, would-be revolutionaries plotted and bombed. As an Army counterintelligence analyst at the Pentagon, he found himself assessing this tinderbox and keeping track of a former classmate turned domestic terrorist. Separately he probed espionage and sabotage threats to the country’s first anti-ballistic missile system. As a political activist, he later worked to unseat Chicago boss Richard J. Daley. As a lawyer, he represented one of America’s richest scions and fought for a historic news organization before arriving at an unlikely adventure. Musty old Encyclopaedia Britannica pioneered the multimedia search system ─ a keystone of the internet ─ and Bowe’s job was to shepherd this invention to fruition. All these stories are about battles won and lost in an America upended and range in time from the political upheavals of the 1960s to the societal revolution brought by the Digital Age. As is true with all battles won or lost, these tales offer up a host of winners and losers. Most show us an America at its best. When human failings take the lead, we occasionally see that part of America as well.

Author’s Note

“In early 2020, I feared my increased irritability during the ensuing lockdown could be a telltale sign I was descending rapidly into curmudgeonhood. Thinking this would be unfair to the dogs, not to mention my wife, Cathy, I decided I needed a project to keep my head straight. I started thinking and writing about several of the strange periods I had lived through in the years since my graduation from law school in 1967."

Take a peek inside Riots & Rockets

Kwajalein Missile Range was then the western terminus of the Pacific Missile Test Range. Today it is formally known as the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Test Site.

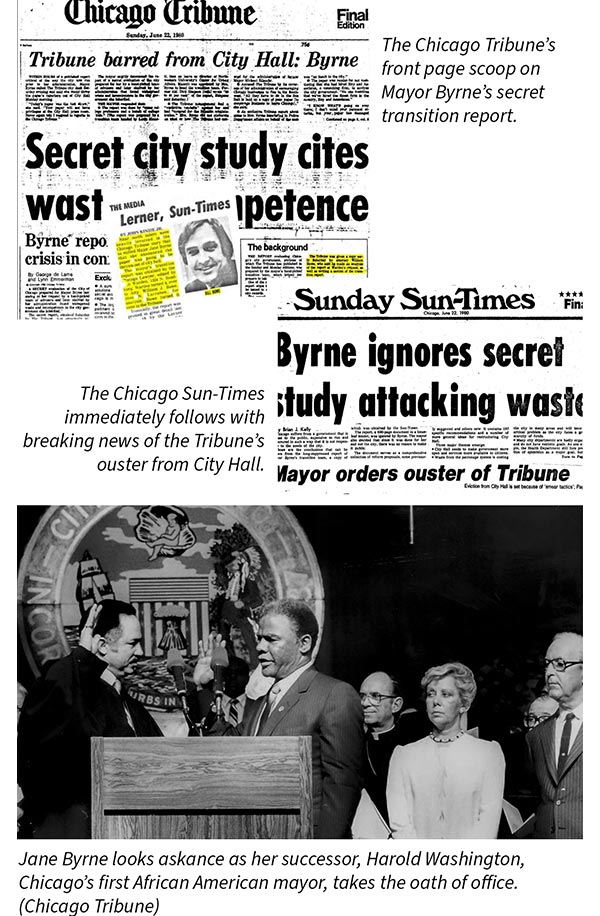

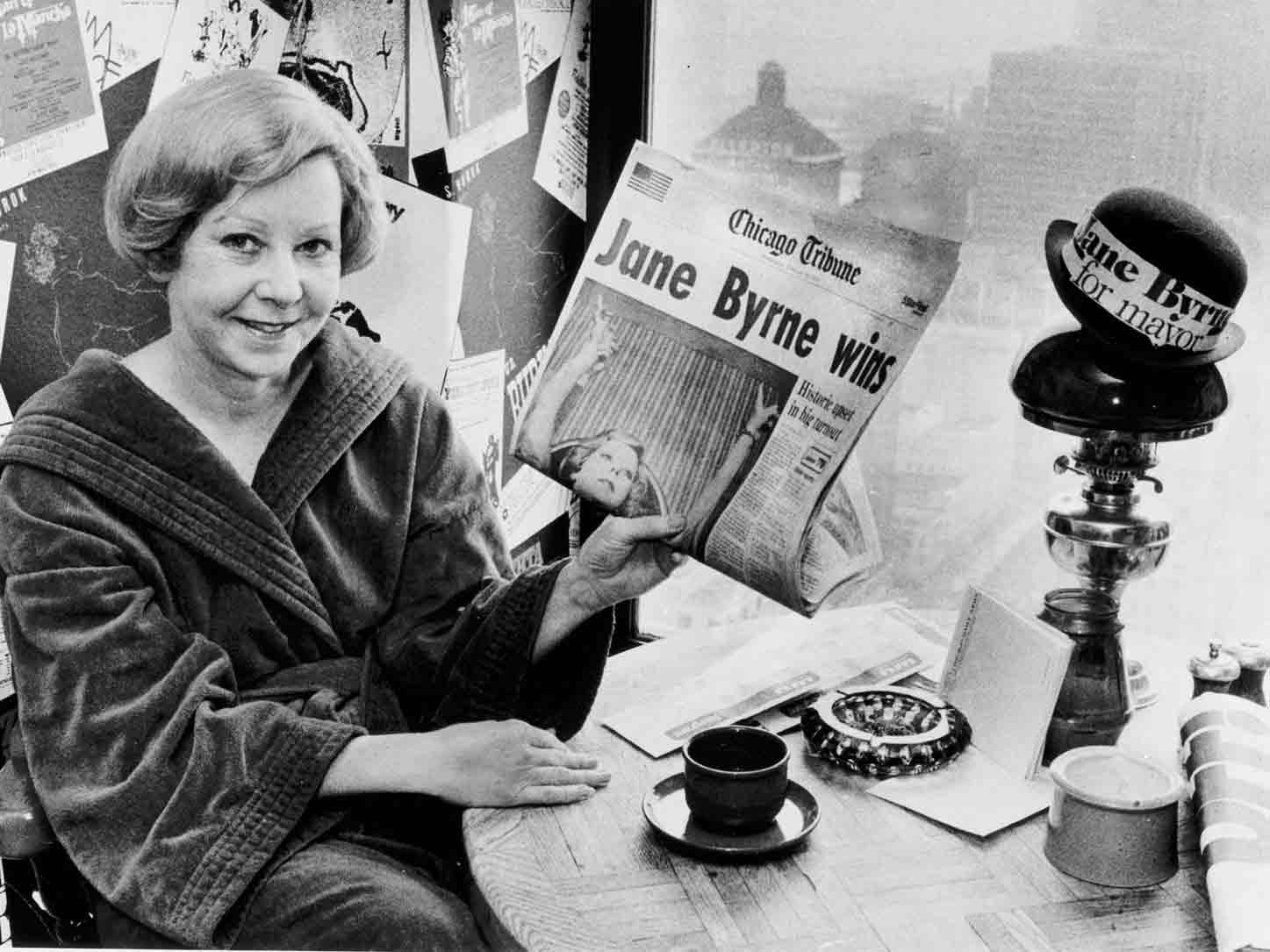

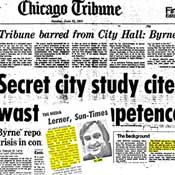

An unusually prominent front page story appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Sunday, June 22,1980. It reported details of Mayor Jane Bryne’s transition team report and revealed me to be an author of part of the previously secret study, as well as the immediate source of its startling revelations.

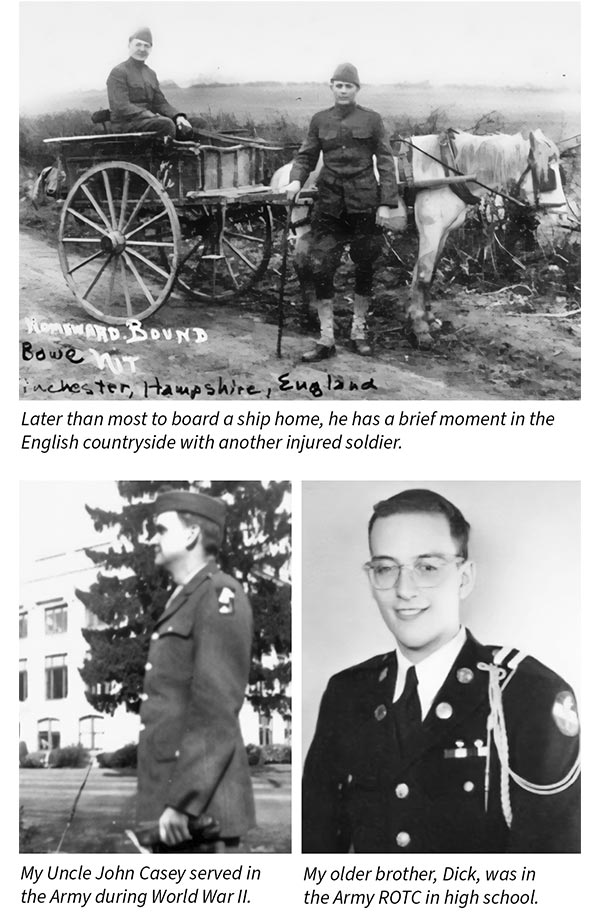

Riots and Rockets – Army Days (1968-1971)

Becoming a General Counsel

Jane Byrne Burned – Chicago Politics in the 1970s

Before the Deluge – United Press International