On the Way to UPI

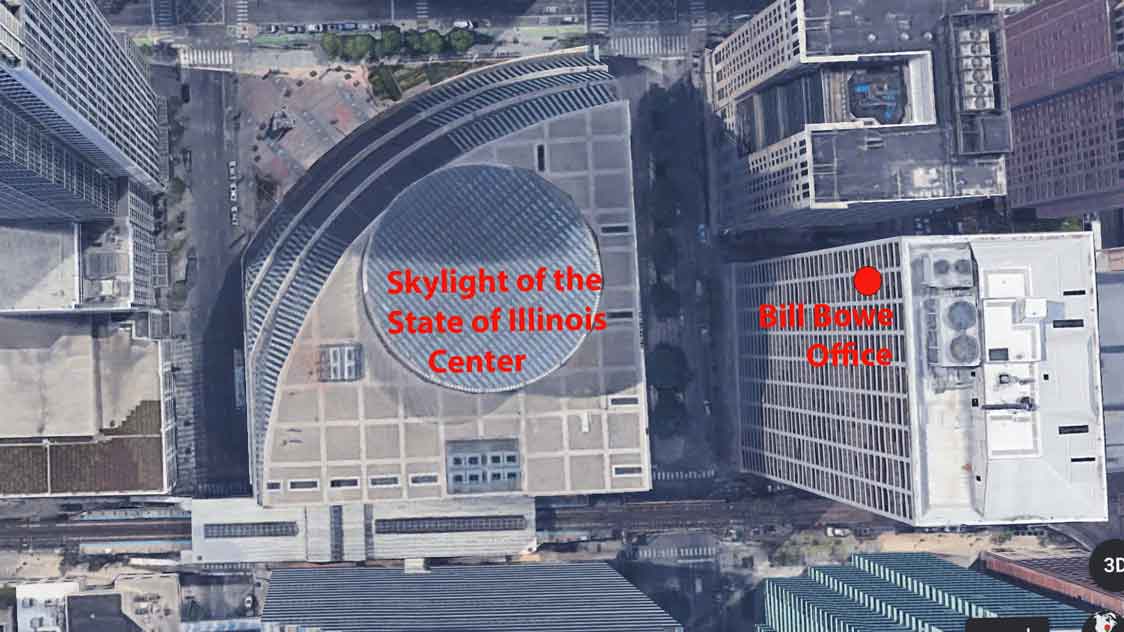

After I left Bradford in 1983, I briefly settled back into the practice of law. Joining several of my former Roan & Grossman partners as Of Counsel, I worked in a LaSalle Street office across from architect Helmut Jahn’s nearly completed State of Illinois Center (later the James R. Thompson Center). My strongest memory of this short period is not the legal work I did but rather being at eye level with the glass dome under construction atop the unique 17-story building. It was impossible not to frequently stare out the window at the steel workers clambering along the yet to be glazed skylight structure above the building’s atrium. Their ballet-like, death-defying, angled tightrope walks were so gripping that anyone watching it for long could fairly be accused of having the morbid curiosity worthy of a Formula One fan.

Notwithstanding this distraction, I continued to do some carryover corporate work for Bradford and general legal matters for other clients. One matter in particular I remember working on was an odd problem that cropped up in the administration of an estate. My friend Arthur Cushman had recently started a long-planned vacation trip across the Canadian Rockies. He was headed westbound to Vancouver from Toronto on a Via Rail Canada train. He never made it. Though only in his early 50s, a contemporaneous police report said he that not long after leaving Toronto he had been eating dinner in the dining car when he suddenly stood up, grabbed his chest, collapsed, and died. I knew he had had heart troubles in the past, but the report of his grand mal seizure and sudden death had come as a shock to me and all those who knew him.

Arthur Cushman wearing Bolo Tie Clasp

The executor of his estate retained me to track down several missing items known to be on his person when he died. Strangely, they had not been on him when his remains were claimed by next of kin. One item was a money belt that he always wore travelling. It was said to have $200 of mad money in it. The other missing item was of more sentimental value, a gold Bolo sheep’s head tie clasp that was always a part of his informal string tie attire.

The train crew had promptly alerted Via Rail’s far away dispatcher, who in turn contacted authorities in the first available stopping place along the route.

Cushman was tall and very heavy and, when I later talked to the local sheriff, I learned that his corpse had been offloaded from the train with some difficulty. The body was put in an ambulance in a sparsely populated location and driven to the nearest mortuary.

The sheriff took my report of the missing items seriously and, amazingly enough to me, he mostly solved the mystery of the missing items. It turned out the ambulance driver and his assistant couldn’t resist temptation. It had been a dark night when they picked up the body after all, and the only other person around them as they drove to the undertakers would never be able to tell the tale of their filching. Confronted by the law, they had given up the gold Bolo tie clasp without ado, disclaiming any knowledge of what might have happened to the cold, hard cash. Although I never found out, my guess is that in return for giving up the clasp, the sheriff let the matter ride.

My priority in this period was to find another corporate law position. In pursuit of this goal, I began to talk to friends and family and other lawyers I knew for advice and pointers to possible opportunities. One of those I talked with was a classmate of mine at the University of Chicago Law School, Linda Neal (then Linda Thoren). One of the few women in the class that graduated with me in 1967, Linda had first worked in the development office of the University and later at the Art Institute of Chicago. At this time, she was an associate in private practice with the large Chicago firm of Hopkins & Sutter. There she was doing legal work for Cordell Overgaard, a partner at the firm who was representing new owners of the United Press International wire service.

UPI – Perennial Second Banana to the Associated Press

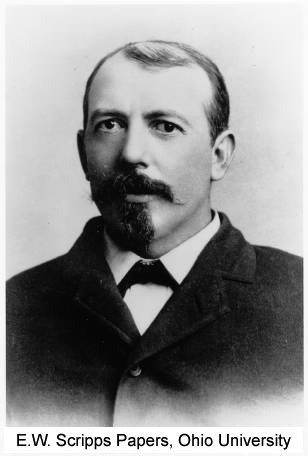

United Press had been founded in 1907 by E.W. Scripps, the owner of newspapers in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo. The papers covered local news in these cities adequately but were at a disadvantage in covering non-local news. The competitors to Scripps had inexpensive access to news stories outside their local markets because they had access to the Associated Press wire service and Scripps did not. AP was a standalone cooperative news gathering organization created and funded at the time by its members, most of the country’s largest newspapers. With these newspapers making all of their own coverage available to their AP cooperative, the AP was able to telegraph these local stories to all the other AP members.

The cooperative newspapers that owned AP had solidified their monopoly on this kind of economic news reporting by making it against AP policy for it to sell to more than one newspaper in each market. This had forced Scripps into the uneconomic step of beginning to put its own reporters in cities in which it had no newspaper or way to offset the cost.

The answer to this problem that Scripps arrived at was to create a competitor to AP. After some years, his United Press had a small number of correspondents in cities that were transmitting about 12,000 words of Morse code over leased telegraph lines to 369 newspapers.

In later years UP grew to be a worthy competitor to the AP, but throughout the decades always remained second in size and scope to the AP. What it lacked in AP’s deeper resources, it tried to make up for with a colorful focus on people and succinct lively reporting. It took pride in its scrappy reputation as the Avis to the AP’s Hertz and continuously over its long competition with AP scored many news scoops.

In the late 1920s, UP’s head briefly met with William Randolph Hearst to discuss merging with the Hearst newspaper chain’s competing International News Service, INS was having its own difficulties competing with the AP behemoth at the time. According to the history of UPI in the book Down to the Wire, written by Gregory Gordon and Ronald Cohen, Hearst is said to have replied, “You know a mother is always fondest of her sickest child. So, I guess I will just keep the INS.” However, in 1954, three years after Hearst’s death, the mother of INS was no longer in the picture. The merger went forward and the United Press became United Press International.

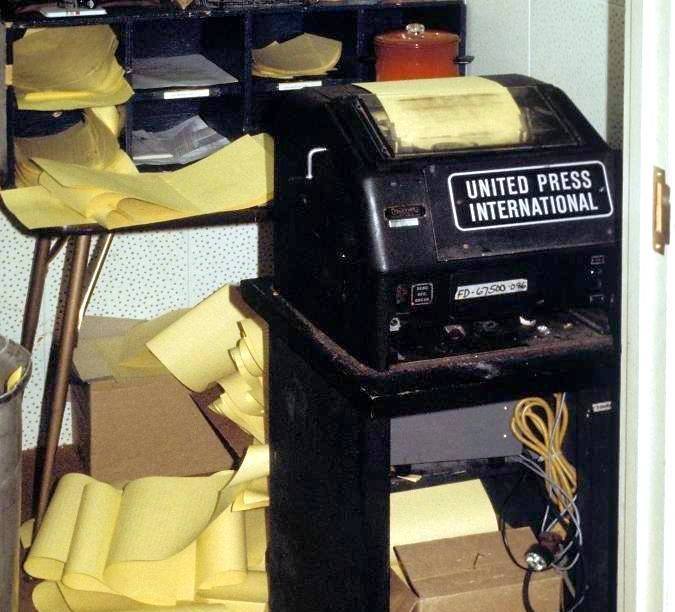

In the next two decades, UPI thrived. By 1975, it counted 6,911 customers. Its main revenue producers then were 1,146 newspapers and 3,680 broadcasters. Technology advances in computerization had brought teletype machine advances, but cost-saving satellite technology was still in the future.

After 1975, the continuing movement of advertising dollars from newspapers to television had begun to sharply reduce the number of afternoon newspapers in the country. This had an increasingly negative effect on UPI’s finances. In the late 1970s, UPI merger talks with CBS, National Public Radio, and other possible buyers went nowhere and Scripps’ executives went public with news that it was interested in a sale or other divestiture of UPI. By 1980, a quadrennial year with extra news expenses for both the presidential election and the Olympics, the Scripps chain was forced to underwrite a $12 million annual operating loss at its UPI subsidiary.

220 East 42nd Street NYC Newsroom 1981

With no responsible parties in the news business stepping up to the plate with an offer to take UPI off its hands, the E.W. Scripps Family Trust, which owned the newspaper chain, began pressing for a sale of UPI on any basis. Beneficiaries of the Trust were Scripps family heirs. Trustees of the Trust, owing a fiduciary duty to the heirs, were increasingly concerned that it the Trust continued to own UPI, at some time in the future the trustees might be subject to up to $50 million in unfunded pension liabilities. They were also worried that lawsuits could also be brought by the heirs against the trustees for wasting the Trust’s assets by continuing to fund the losses of a wire service that no longer was essential for the Scripps newspapers to own.

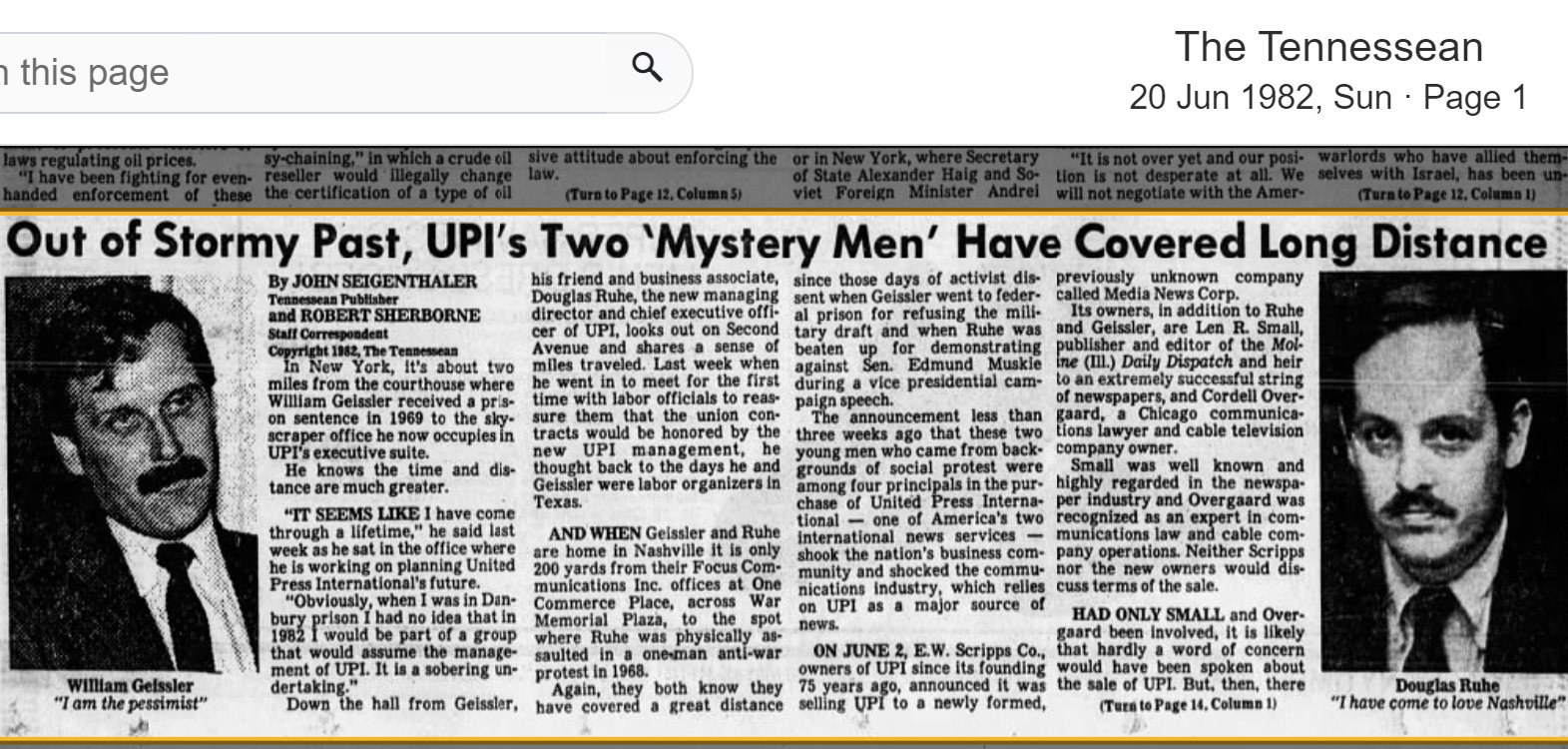

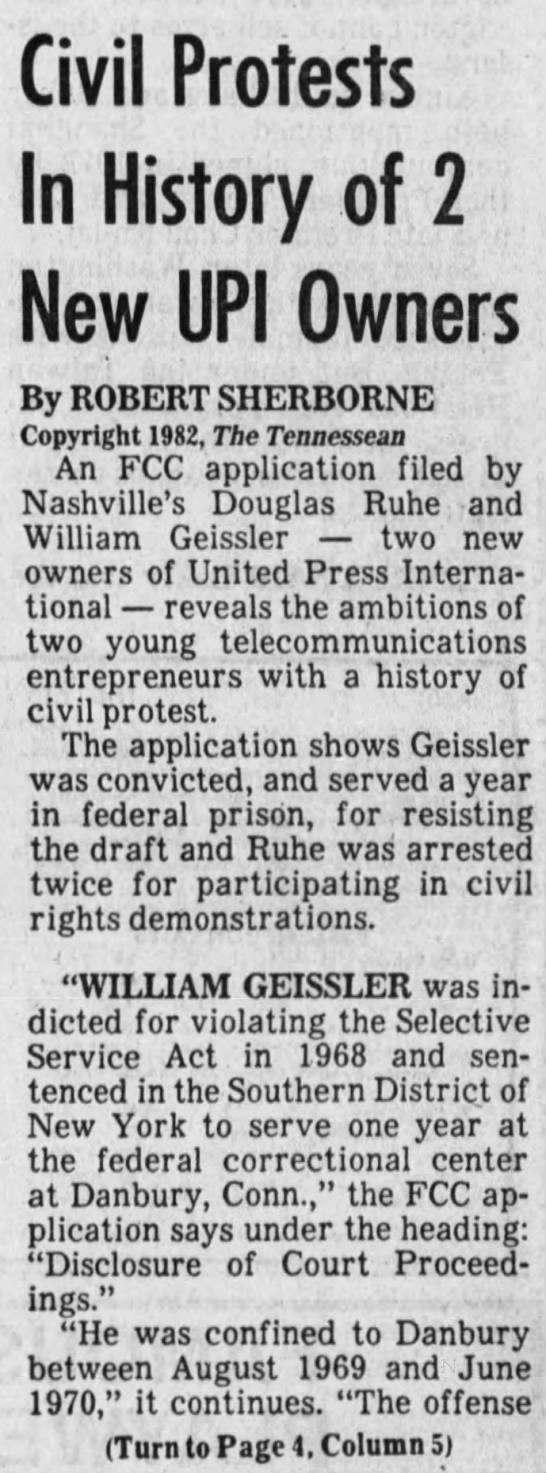

Enter at this propitious moment, Douglas Ruhe and William Geissler. They bought UPI from Scripps for $1 in June 1982.

Douglas Ruhe and William Geissler

UPI’s new owners, Douglas Ruhe and William Geissler, were young Nashville entrepreneurs. Though they had started out with little business experience or capital, their small Nashville company, Focus Communications, had successfully taken advantage of a minority set- aside program of the Federal Communications Commission and had been issued one low-powered television license in Illinois and had several others pending.

Ruhe had grown up in an unusual family. His father, Dr. David Ruhe, was appointed the first professor of Medical Communications at the University of Kansas Medical School in 1954. Dr. Ruhe was a medical educator who made more than 100 training films. A member of the Baha’i Faith, he was later elected Secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahais of the United States. As the Baha’i Faith has no clergy, it is governed by elected spiritual assemblies. Then from 1968 to 1993, the senior Ruhe served as one of the nine members of the representative body of the global Baha’i community, the Universal House of Justice of the Bahai Faith resident in Haifa Israel. Dr. Ruhe had also long been active in civil rights, working in Atlanta in the 1940s to increase the hiring of African American police officers, and in Kansas City in the 1960s in protesting segregation.

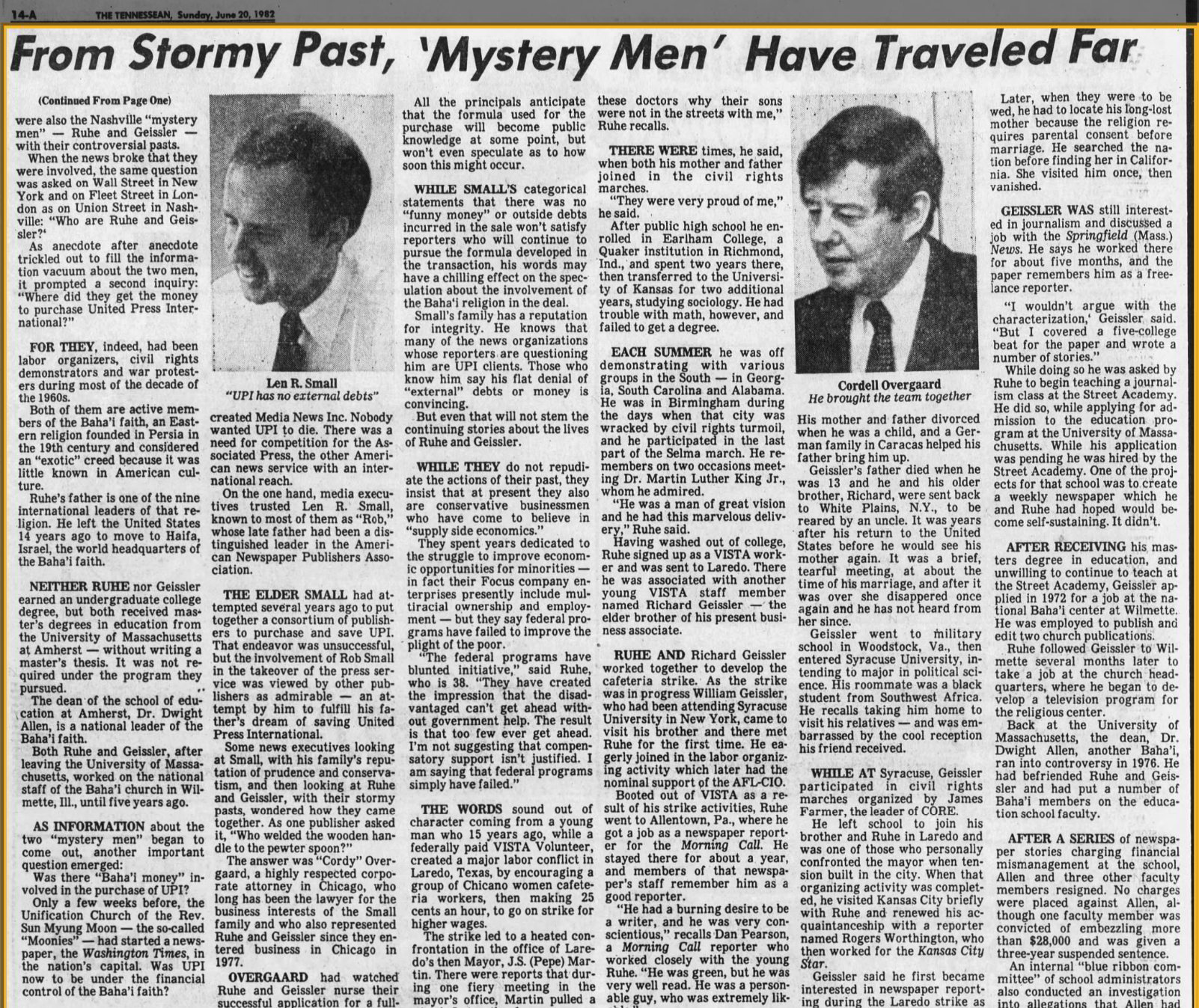

His son Doug had followed his father in the Bahai faith. He had met Bill Geissler when both attended the University of Massachusetts. When they bought UPI in 1982, a lengthy profile of the pair was published in Nashville’s newspaper, The Tennessean. The Tennessean reported that neither Ruhe nor Geissler had ever received an undergraduate college degree. Ruhe explained to the Tennessean that he had studied sociology for a time at the University of Kansas but left without his degree because he was “bad with math.” Oddly, they had nonetheless both received master’s degrees in education from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. This likely was related to the fact that the dean of the education school, Dr. Dwight Allen, was a national leader of the Baha’i faith and the program had no requirement for a master’s thesis in order to earn the degree.

After receiving leaving school, both Ruhe and Geissler worked together on the staff of the Baha’i denomination in the 1970s at The Bahai National Center in Wilmette, Illinois near where Dr. Ruhe lived. In 1977, with a loan from Ruhe’s mother-in- law, the two joined with a Korean-born graphics designer they knew from their Baha’i work and started a small public relations firm in the attic of Ruhe’s home in nearby Evanston.

In 1980, under President Jimmy Carter, the Federal Communication Commission had launched a program to “let the little guy” get into commercial television broadcasting. The idea was to ease licensing requirements and financial hurdles for low-power TV stations that would have a small range of 15 miles, rather than the average 50 miles for full-power stations. The thinking was that these stations would be cheaper to build and minorities and more single station owners would be able to get a broadcast license. Applicants for low-power stations also would no longer have to prove they had the financial wherewithal to actually make a go of it.

By 1985, many of the 40,000 applications received were for overlapping geographic areas. In these cases. licenses had been awarded in over 300 lotteries. To steer more applications to minority applicants and increase their chances of beating out non-minority applicants, minority applicants were given more lottery numbers. With Doug Ruhe married to a Black, and their Korean-born partner married to a Native American, enough boxes were checked for several low-power licenses to be pending or issued to their Focus Communications enterprise. The issued license at the time was for Channel 66 in Joliet, Illinois near Chicago. The then chief of the FCC’s low-power TV branch, Barbara Kreisman, estimated that minorities, with given extra numbers to play with in the lottery, had won about two-thirds of the lotteries they had participated in.

At fandom.com, the self-described “world’s largest fan wiki platform,” I found a brief history of Ruhe and Geissler’s Joliet station WFBN. In its early days its scrambled signal gave low-power television stations wide programming latitude to attract a paying, subscription audience.

“Independent station WFBN. Originally owned by Nashville- based Focus Broadcasting, it initially ran local public-access programs during the daytime hours and the subscription television service Spectrum during the nighttime. By 1982, WFBN ran Spectrum programming almost 24 hours a day; however, by the fall of 1983, Spectrum shared the same schedule with that service’s Chicago subscription rival ONTV. The station as well as ONTV parent National Subscription Television faced legal scrutiny because of its lack of news or public affairs programming and was faced with class action lawsuits because of the pornographic films aired by ONTV during late-night timeslots, with some of these legal challenges continuing even after ONTV was discontinued; however, a ruling by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) permitted broadcast television stations to air content normally considered indecent through an amendment to its definition of what constituted “public airwaves” declaring that “broadcasts which could not be seen and heard in the clear by an ordinary viewer with an ordinary television” were exempt, as long as the signal was encrypted.”

Having vaulted into the ownership of several active and pending television station licenses, Ruhe happened to see a Wall Street Journal article in 1982 that E.W. Scrips, Co., having failed to sell UPI to other buyers, was considering selling the company to National Public Radio, a private and publicly funded not-for-profit company. Ruhe immediately focused on his next goal, buying UPI.

Knowing that they lacked experience in the news business, they contacted the lawyer for their earlier public relations firm, Cordell Overgaard, a partner in Linda Neal’s law firm of Hopkins & Sutter. Overgaard put them in touch with Rob Small, another client of his and a publisher of several small Illinois newspapers. Ruhe and Geissler thought Rob Small would be a good partner and agreed he would be Chairman of UPI after the sale. This choice lent a needed patina of credibility to their bid to buy UPI. Also, joining their effort to buy UPI was a fresh Baha’i graduate of Harvard Business School, Bill Alhauser. He became UPI Treasurer. Ruhe and Geissler initially had a 60% interest in UPI, Rob Small and Overgaard got 15% each, and Alhauser and another financial advisor, Tom Haughney, 5%.

Scripps had diligently been trying to sell UPI for five years at this point and was ready to throw in the towel. To finally get rid of it to Ruhe and Geissler, they offered to loan UPI $5 million interest free in working capital and put another $2 million plus into its pension funds. For their part, Ruhe and Geissler put up the proverbial $1. On June 3, 1982, UPI was theirs.

What they had bought was the second largest generator of news on the planet, with more than 200 bureaus around the world and over 1,500 employees writing, editing and distributing over 12 million words of news daily.

The purchase by Ruhe and Geissler got a rough reception once its customer base of newspaper publishers heard of the sale. Their unease was accentuated when The Nashville Tennessean newspaper reported that both men had previously been arrested, Ruhe in a civil rights demonstration and Geissler for draft evasion. Geissler had even served a year in federal prison as a result.

Following their purchase of UPI, operational chaos was quickly the order of the day in upper management. UPI’s carryover President was shown the door and a former news executive with NBC and CBS, Bill Small (no relation to Rob Small), arrived as an expensive replacement. Small had no experience in the wholesale news business, but he at least gave Ruhe and Geissler a known figure in the news business to be the public face of UPI.

After the purchase UPI’s owners commissioned International Management Consultants in New York City to assess the long-term strategy for UPI. With losses on the order of $1million a month, time was clearly of the essence. The firm’s considered recommendation was to immediately and substantially reduce the number of editorial employees. Ruhe rejected the advice, citing internal pushback from UPI’s managers and with dissent being registered by minority owners Rob Small and Overgaard, UPI’s Treasurer Alhauser directed the company’s Controller to stop sending Overgaard and Small monthly financial statements.

The upshot was reported in the article UPI’s Disaster – What Went On and What Went Wrong by Katharine Seelye and Lawrence Roberts that appeared in the September/October 1985, edition of Columbia Journalism Review:

To Rob Small and other executives, this was just one more indication that there was no realistic strategy for putting UPI on track. Ruhe and Geissler “had tenacity, energy, street smarts, charisma, and some classic entrepreneurial skills,” says Small, who is back behind his desk at the Moline, Illinois, Daily Dispatch, of which he is editor and publisher. “But the key was that they lacked a sense of organization, of priorities, a sense of urgency. They didn’t know the big problems from the little problems, and we had a big problem the meter was running.” The company was losing $1 million a month. In mid-January 1983, Small and Overgaard decided to confront Ruhe and Geissler with what they saw as the company’s problems and to vent their dissatisfaction. On January 26, at a meeting in Ruhe’s room at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York, they told Ruhe and Geissler that the company needed between $6 million and $15 million. Ruhe disagreed. Then, Small recalls, “I tried to get across to Doug (Ruhe) that he was a creative, imaginative guy but that we needed a more methodical person to run things. He wasn’t interested. He just shook his head. There wasn’t that much dialogue. Cordy and I said we would step aside. There wasn’t a big fight. “Says Overgaard: “I think their reaction was one of relief.”

Gordon and Cohen’s Down to the Wire provide a similar account of Small’s and Overgaard’s reaction to what had happened in the short time that had elapsed since the purchase of UPI:

Ruhe and Geissler, they felt, were lost in dreamy idealism that distorted their business judgement. If their partners were going to run UPI into the ground, Small and Overgaard wanted no part of it.

Other major changes in management followed in 1983. Australian Maxwell McCrohon, the Chicago Tribune’s Vice President for News came in as UPI’s Editor-in-Chief and Luis Nogales, a Vice President in Gene Autry’s Golden West Broadcasting, arrived as Executive Vice President.

Other major changes in management followed in 1983. Australian Maxwell McCrohon, the Chicago Tribune’s Vice President for News came in as UPI’s Editor-in-Chief and Luis Nogales, a Vice President in Gene Autry’s Golden West Broadcasting, arrived as Executive Vice President.

Moving to Nashville as UPI Assistant General Counsel

Ruhe and Geissler had made Linda Neal UPI’s General Counsel after their purchase of UPI. They also had decided to save money by moving UPI’s news headquarters from Manhattan to Washington, D.C., and the company’s corporate headquarters from Scripps’s offices in Cincinnati to Nashville, where both Ruhe and Geissler then lived.

UPI Office, 1400 I Street, Washington, DC

With UPI having moved out from under the Scripps administrative umbrella, the company needed to create a standalone internal law department for the first time. Linda had a varied practice at Hopkins & Sutter and had no desire to fill this role by moving to Nashville. She remembered that I was looking for a corporate law position and that I had already created one law department from scratch at Bradford. She asked me to think about starting UPI’s law department in Nashville and serving there as the company’s Assistant General Counsel.

On the plus side, this sounded like a good opportunity, though on the negative side it would entail moving with Cathy and our three-year- old son Andy to Nashville. It was certainly worthy of a serious look on my part, so I travelled to Nashville to meet with Ruhe, Geissler and Alhauser to learn more about UPI’s plans and finances.

I first met with Ruhe in the pie-shaped Focus Communication office in the Union Bank of Commerce in downtown Nashville. Ruhe was a whirlwind of upbeat blather, who presented himself as a know-it- all, “I see the future!” business wunderkind. He explained to me more than once that owning a television station was like having “a license to make money.”

My dinner meeting with Geissler was, in a Pythonesque way, something entirely different. Geissler had been born in Venezuela and was fluent in Spanish as well as English. During dinner, he strangely had little to say in either language about anything. For whatever reason, he remained largely catatonic throughout our meal.

Since Linda had little direct knowledge of the company’s current financial condition, she had steered me to UPI Treasurer Bill Alhauser for the straight dope. I was entirely focused on the state of UPI’s finances when we met and my questions to the mild-mannered Alhauser about the company’s financial position were very direct. As I later found out, I was not the only one he regularly misled. As a result, while I had met the three principal operating managers of UPI, and was generally aware of its turnaround posture, I hadn’t a clue the company would crater in the next 18 months and that I would get the post-graduate education in bankruptcy law that I never got in law school. Contrary to the rosy picture painted by both Ruhe and Alhauser, UPI actually ended 1983 with a loss of $14 million and was facing debts of $15 million. Peanuts today perhaps, but a lot of money in 1983.

Though I didn’t know it at the time I was meeting with Ruhe, Geissler and Alhauser, UPI was regularly having a hard time meeting payroll. Fortunately for UPI, Tom Haughney found that Los Angeles-based high-risk lender Foothill Capital Corporation was willing to lend UPI

$4 million. The loan would cover payrolls for a period of time and would help deal with arrearages due AT&T and RCA. Unfortunately for UPI, the loan carried an interest rate of 14.25%, three points above prime in that period of still high inflation.

8245 Frontier Lane, Brentwood, TN

With this background that I knew nothing about, in early 1984 Cathy, Andy and I settled into our new home in the Nashville suburb of Brentwood, not far from UPI’s new business headquarters there.

UPI Begins Its Descent into Bankruptcy

In scrambling for cash to meet payrolls, UPI at this time was awash with highly paid consultants. Disadvantaging UPI’s growing legion of creditors, Baha’i friends and acquaintances of Ruhe and Geissler increasingly began to propose and execute purchases of UPI assets on extremely favorable terms. Major staff cuts and salary reductions and sweetheart asset divestitures were the order of the day.

Ruhe and Geissler also continued to siphon cash from the company through payments to their Focus holdings. Though not seen in financial statements, under pressure to deliver a life-saving loan to the company, Alhauser later revealed the Focus had been receiving $150,000 to $200,000 a month from UPI. This was far in excess of Ruhe and Geissler’s salaries. According to the book Down to the Wire in 1984:

UPI was sinking in debt, swamped by its staggering communications burden, by the costs of the moves, by fees to a proliferation of highly paid consultants, and by costly joint-venture deals. Compounding the problem was the owners’ secret transfer of cash from UPI to Focus. During 1983, it would total $1.434 million.

The dire straits the company was in could be seen in the explosion of trade creditor debt. AT&T and RCA Service Company were several of UPI’s largest trade creditors. UPI was getting way behind in paying the monthly cost of leasing the telephone lines and teletype machines that were essential to running its offices and carrying news stories to its customers.

The Richard Harnett and Billy Ferguson book Unipress, a history of UPI in the 20th century, reports that the UPI Controller in this period couldn’t convince Ruhe that UPI was running out of money and was regularly disparaged by Ruhe as a “bean counter” for his efforts. The Treasurer Alhauser was said to be either oblivious to the problem or not willing to confront Ruhe and Geissler about money. The exceptional rise in accounts payable produced a bizarre administrative fiasco.

To ensure a smooth transition, Scripps had agreed to handle UPI’s payables for a period of time after the sale to Ruhe and Geissler. At a later point, UPI’s finance department needed to manage the task of sending checks to vendors and suppliers. When the cutover came, UPI’s computer was duly programmed to print out these checks as soon as the invoices for these expenses were approved. However, UPI’s Controller was in no position to mail checks if the funds in the company’s checking account wouldn’t cover them.

Payroll, rent, telephone and teletype service were all top priorities, but even here arrearages began building up. When a lower-priority check would produce an overdraft if cashed by the payee, it would be held

back and the check would be put in the Controller’s desk drawer until later. In a sign of impending disaster, at one point nearly $1 million in checks had piled up in the Controller’s desk.

These financial problems continued to be ignored and Ruhe and Geissler shortly threw a lavish party to celebrate the opening of its new Washington, D.C. news headquarters. For a company headed down the tubes, an inexpensive press release announcement might have been more sensible alternative than an over-the-top, costly blowout. In the 9th floor executive suite of a newly constructed 12- story building above the subway station at 14th and U Streets, hundreds of high mucky- mucks from Congress and media organizations milled about the new space feasting on tray after tray of hors d’oeuvres and drinking case after case of spirits and champagne. Gordon and Cohen in Down to the Wire succinctly said of the party, “Ruhe and Geissler spent money as if they had it.”

The main newsroom had been successfully moved from Manhattan to the new building but moving the New York radio studios for UPI’s news reports on the hour and half-hour proved to be a major problem and caused a massive cost overrun in the budget for the move. It turned out no one had thought about recreating the necessary soundproofing for the Washington studios. Part of the new offices had simply been partitioned off with glass walls and fitted with desks and microphones.

Site of Washington, DC Broadcast Studio Debacle

Immediately the many radio stations across the country dependent on retransmitting these reports complained that the voices of UPI’s commentators were hard to hear. The problem was low frequency background noise from the heating and air conditioning fans in the ceiling ventilation ducts. Fixing this was a complicated tasks that both disrupted the broadcast part of the business and cost an arm and a leg as well.

UPI Sells Its Crown Jewel Picture Service to Reuters

Reuters Headquarters, 85 Fleet Street, London

By spring 1984, UPI was again running out of cash. Desperate to stave off the loss of control that would come with bankruptcy of UPI, Ruhe had decided to sell off UPI’s crown jewel, its newspicture service. This was an international enterprise that sold pictures of breaking news from around the world to all UPI’s newspaper clients. Mike Hughes, UPI’s head of the picture service, thought the estimated cost to recreate the asset would be on the order of $25 million. Ruhe began secret sale negotiations in Brentwood with Peter Holland, an executive of the London-based Reuters.

Holland must have seemed certain he would shortly strike a deal with Ruhe. Reuters was about to go public in a stock offering and in a June 4, 1984, sale prospectus stated that it would soon enter into a five-year joint venture agreement that would obtain UPI’s overseas picture business for $7.5 million. This was even before Holland got on an airplane to Nashville to firm up the details of the deal.

Not long after he arrived, Ruhe called me into his Brentwood office where he was meeting with Holland and told me to memorialize in a memo the terms of the agreement they had just struck. UPI was to get an immediate infusion of $3.3 million in cash, with another $2.4 million in 60 monthly installments. In return, Reuters would acquire UPI’s foreign photo staff and send Reuters pictures of American news events. UPI would receive the non-U.S. pictures of the expanded Reuters service but would have to let Reuters gain a foothold in the U.S. by permitting its output to be sold to such large papers as the Washington Post, Baltimore Sun and New York Times.

Shortly after news of the deal leaked, Linda Neal and Bill Alhauser met Ruhe for breakfast. When both raised questions about the deal. Down to the Wire reports Ruhe shut them down saying, “Look, the deal is done! Just get the thing signed!” At that point, I got on the next plane to London to negotiate the formal terms and legal details of the agreement that both parties would sign. Not surprisingly, this turned out to be a very one-sided affair.

Normally in a contract negotiation there is always some back on forth as the secondary business terms are put to paper. Holland was quite smart and new that there was little leverage on the UPI side to negotiate even minor points. Nonetheless, Holland and I closeted ourselves in the Board of Directors room of the Reuters headquarters at 85 Fleet Street in London and started our discussions. Watching over our negotiation across the large boardroom table was a portrait of founder Paul Reuter staring down at us.

Paul Reuter (1816-1899)

We had made some progress during the daylight hours when the unexpected occurred. After a knock on the door, we were served with papers issued by a New York court stating that signing the agreement and going ahead with the transaction was prohibited.

Once the shock wore off, we began assessing this development. We ultimately decided to ignore the development and proceeded to finalize the agreement. This took hours and had us spending the night in the board room. Then, we not only had to wait for the papers to be typed up in final form, but we had to wait for Ruhe to fly in from Nashville to sign them. Holland relieved the boredom of our board room siege in the early morning hours by breaking out a bottle of Scotch from a hidden Reuters liquor stash. He proved to be a delightful and convivial business opponent as we took a break waiting for the typing to finish, still on the opposite side of the table.

Back in Nashville, Jack Kenny, the newly hired financial operating officer brought in at Foothill’s insistence to cover for the inexperience and befuddlement of Alhauser, was beginning to clear some of the most pressing vendor invoices. He was being helped by a new Controller, Peggy Self, who had also been brought on as his assistant. They had been hired after Foothill, worried about UPI defaulting on its $4 million loan, had assessed Alhauser as inadequate to the task of managing the company’s finances.

When Kenny and Self arrived in spring 1984, they were immediately confronted with a host of angry creditors and little cash to pay them with. Both were quickly appalled by Ruhe’s instructions to pay his consulting friends and cronies ahead of critical UPI suppliers.

With the $3 million of cash immediately in hand from the Reuters closing, Kenny quickly covered the immediate payroll due, followed by checks to the creditors that were by that time threatening lawsuits for nonpayment. By the time Ruhe had returned to Nashville from signing the Reuters agreement in London, the Reuters cash was completely gone.

As summer 1984 wore on, another Baha’i friend of Ruhe, continued to chase payment for enormous consulting fees for an automated accounting system he promised UPI but never delivered. When I joined Kenny and Self urging Ruhe to further postpone payment to this non-critical vendor, Ruhe was adamant in ordering immediate payment. For Self, it was the straw and broke the camel’s back. She shortly departed for the more pacific world of the Baptist Sunday School Board.

Luis Nogales in his role as UPI’s Executive Vice President in New York increasingly became aware of the dire financial straits the company was in. I had no sooner returned to Nashville from concluding the sale of UPI’s photographic business in London, than Nogales had concluded employee layoffs and salary cuts needed to be immediately negotiated with the Wire Service Guild union if UPI was to avoid going under.

Gordon and Cohen in Down to the Wire report that Geisler was blind to this reality and wrote an angry letter to Nogales ordering him out of the negotiations with the wire service union, saying along the way, “All you MBAs think the only way to solve problems is pay cuts and layoffs. The way to do it is sales and marketing and increasing revenues.”

By early August 1984, Ruhe and Geissler could no longer keep the company’s imminent collapse from the union. Wire Service Guild President William Morrisey was astounded when informed of the peril facing the union’s entire membership. UPI owed creditors $20 million and was losing $1.5 million each and every month going forward. Initially, all concerned believed that UPI should do everything it could to avoid bankruptcy, since such news would have an immediate adverse effect on UPI’s customers and many newspapers would no doubt not renew their subscriptions. Ruhe and Geissler in particular understood that, while not a certainty, UPI filing for bankruptcy could wash them out of any continuing management role and render their ownership interest in the company worthless.

Notwithstanding the fact that UPI President Bill Small continued to turn up in UPI’s New York office every day, as a practical matter in the emerging crisis, Luis Nogales was the person running the operations of the company day to day.

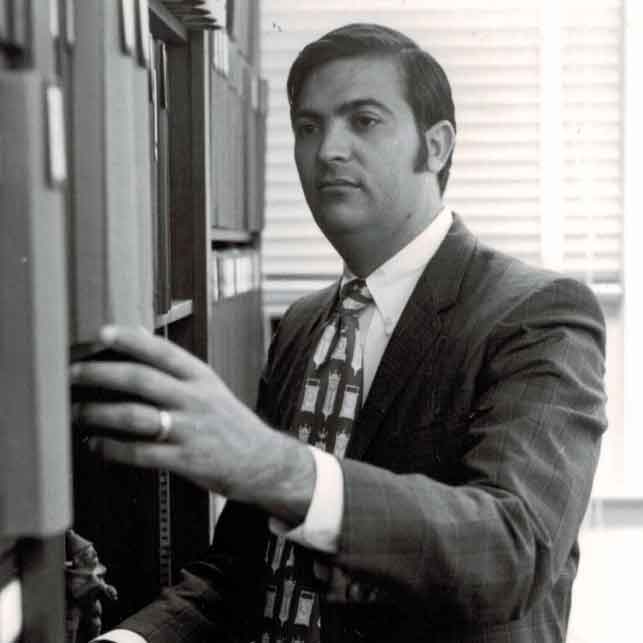

Luis Nogales, Special assistant Stanford University’s President 1970

Coming from humble immigrant origins, Nogales grew up in the agricultural valleys of California near Calexico working as a farm worker. He was able to attend college at San Diego State University and, in 1969, he graduated from Stanford University Law School. When he was inducted into Stanford University’s Multicultural Hall of Fame in 2004, his profile had this to say about him:

Mr. Nogales has had a full and active career in the private sector and public service. He served as CEO of United Press International and President of Univision, among senior operating positions; in addition, he has served on the board of directors Levi Strauss & Company, The Bank of California, Lucky Stores, Golden West Broadcasters, Arbitron, K-B Home, Coors, and Kaufman & Broad, S.A. France. He also served as Senior Advisor to the Latin America Private Equity Group of Deutsche Bank working in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico. On corporate boards he has been an advocate for diversity of the workforce and senior management. While assuming leadership positions in the private sector, Mr. Nogales continued participating in public service by serving, among other activities, as a Trustee of the Ford Foundation, The Getty Trust, The Mayo Clinic Trust, and Stanford University. He also served on the board of directors of the Inter-American Foundation, The Inter-American Dialogue, The Pacific Council on Foreign Policy and The Mexican and American Legal Defense Fund, (MALDEF) where he served as president of the Board.

Not surprisingly, as the company’s financial condition deteriorated, I worked increasingly with Luis both before and after I became UPI’s General Counsel. As his dispute with Ruhe and Geissler came to a head as to who should be managing the company, it wasn’t hard to see what the better outcome for the company would be. With Ruhe and Geissler, you had would-be boy wonders who had briefly gamed the minority lottery set aside program of the FCC to transitory wealth. Though poor in cash, good sense and management experience, they were possessed with a high energy impetuousness and good luck. This had permitted them to leverage their position beyond anyone’s wildest expectations into the ownership and control of UPI. However, having won a prize they were ill-equipped to deal with, they had in short order run UPI into the muck with a speed fast enough to make your head spin.

With the fate of UPI now hanging in the balance, you didn’t have to be a seer at this point to recognize that the company would be better off having its debt and management reorganized under the federal bankruptcy laws. In contrast to Ruhe and Geissler, you had in Nogales the exact opposite choice of someone to carry the company forward in trying times. Trained as a lawyer, and possessed of exceptional leadership and political skills, early in his career he was already a accomplished business person with the experience and intelligence to manage a large, global media company in trouble. My sympathies naturally lay on his side as the management conflict with Ruhe and Geissler came to a head. As our lawyer-client relationship unfolded in this period, we became good friends. On my side, I admired Luis and was proud to know him.

After some effort, and with the grudging consent of Ruhe and Geissler, Nogales was able to open the books of UPI to the union and made sure there was transparency with the union as to the company’s ownership structure and finances. Pursuant to his direction, Linda Neal and I spent a long day with the union negotiators in UPI’s Brentwood office unveiling the strange corporate structure of companies Ruhe and Geissler had erected to serve their interests, if not UPI’s. Morrisey and the others were both shocked and angry at what they learned. With bankruptcy still a real possibility in the short term, the union agreed to job cuts and wage givebacks. The final agreement with the Wire Service Guild called for the wage cuts to expire before the end of 1984.

UPI wasn’t the only thing going south for Ruhe and Geissler at the end of 1984. The use of minority set-asides had indeed brought them success in the early ‘80s with the FCC lotteries granting them multiple low-power TV licenses. If the stations were built, the business model at the time was to acquire paying viewers through subscriptions. This early form of Pay- TV got Channel 66 off the ground in Joliet, Illinois and Ruhe and Geissler’s Focus Broadcasting Company got outside investors interested in putting up the capital for several other small markets. What Ruhe and Geissler hadn’t counted on was the nascent growth of cable television eating into what they thought would be a long- term income stream for such low- power channels. As 1984 unfolded, the program provider for Channel 66 pulled out and the channel began to fill its airways with soft-core porn content and music videos. Ruhe and Geissler began trying to switch the channel to a regular commercial station format and sell it to another operator. If a sale couldn’t be accomplished, Ruhe and Geissler’s entire world might crumble around them.

Down to the Wire describes the period this way:

Nogales’s own illusions about the TV sale were short-lived. Not long after he had delivered to employees the owners’ pledge of a cash injection, he recalled later, he was chatting with Ruhe when the subject of the owners’ investing money from Channel 66 came up. “I wouldn’t risk a dollar in UPI,” Ruhe said firmly. Nogales couldn’t believe what he was hearing. He had just put his reputation on the line for the owners. “Doug,” he said, bristling, “ I went down and told the staff after clearing it with you that you would put $10 million or $12 million from the proceeds of the [TV] sale into UPI.” Ruhe stiffened. “No, I’m not going to put in a dime,” he declared. On many occasions Nogales had gone out of his way to excuse the shortcomings of the owners, who had hired and promoted him. But now, he thought, Ruhe had betrayed him. And betrayed UPI.

With operating cash non-existent, Ruhe decided to borrow from Uncle Sam by not paying the Internal Revenue Service $3 million in employee payroll taxes owed for 1984’s fourth quarter. I had been careful to make sure Ruhe and all the senior executives were aware of the enormous personal exposure this could bring them. Shorting the IRS is one of the great no-nos of running any business, because the owners or executives responsible for making this decision can end up assuming personal liability for the shortfall if the company itself can’t make good on the debt.

This properly scared the bejesus out of Nogales, Kenny, and others. So, when Ruhe and Geissler still hadn’t been able to sell Channel 66 in early 1985, the proverbial excrement began to hit the fan when it became apparent UPI would be unable to pay the now past due taxes. Kenny’s proper response was to promptly inform UPI’s lender Foothill. Foothill executives were not amused, since in a bankruptcy the IRS would have a higher priority for being repaid than even a secured lender like Foothill.

The Los Angeles Blow Up

For some time, it had been the view of Nogales and Kenny that the time had come for Ruhe and Geissler to either sell UPI or send it into bankruptcy court for a restructuring. Now Nogales was making the argument directly to both owners. Recognizing that in either event, they would likely not only lose operational control, but would also walk away with nothing further to gain financially, this was the last thing Ruhe and Geissler wanted to hear. Ruhe had concluded now that he had to get rid of Nogales. In parallel, Nogales had concluded Ruhe and Geissler had to be removed from operational control of the company if it was ever going to recover from the current crisis.

With the owners now at loggerheads with the top managers of UPI, the two factions agreed to meet at the Los Angeles airport on Sunday, February 24, 1985. Foothill had summoned Nogales to be briefed on UPI’s financial status and recovery plan the next day. With primary lender Foothill, UPI’s senior management, creditors, and newspaper subscribers all having lost faith in reign of Ruhe and Geissler, Nogales hoped that they would come around in their thinking given the inability to meet the next payroll coming due. Not to be. Ruhe and Geissler still thought they would somehow muddle through.

John Nickoll, Foothill

When Nogales and UPI’s outside financial advisor Ray Wechsler met with Foothill the next day, things didn’t go well. Foothill executive John Nicholl told them:

“You’d better get the owners back out here. We’re at a crucial point. You guys don’t own the company. You’re managers not owners. Owners need to make the decisions.”

Ruhe and Geissler might ignore Nogales, Wechsler. or Kenny, but they couldn’t have UPI’s prime lender going wobbly on them. When Ruhe and Geissler turned up on Wednesday, they got the following blast from Foothill executives:

“We don’t have confidence you can turn it around. We’re not going to fund the company with its present ownership. Often, in situations like these, management takes over. If you want to work out an agreement where management takes over, we’ll work with you.”

For Ruhe and Geissler that meant giving up any further dismemberment of UPI and swapping their UPI stock in return for creditors forgiving their debts. After dickering Thursday with Nogales and Wechsler, Ruhe and Geissler agreed to the basic outlines of a plan and shook hands on it.

While all this had been going on, I had been in Brentwood and was unaware of the details of what had been going on in Los Angeles. However, as they flew back to Nashville for Los Angeles, Ruhe and Geissler were already cooking up a new Plan B for Nogales.

Down to the Wire records the next chapter in the Los Angeles blow up.

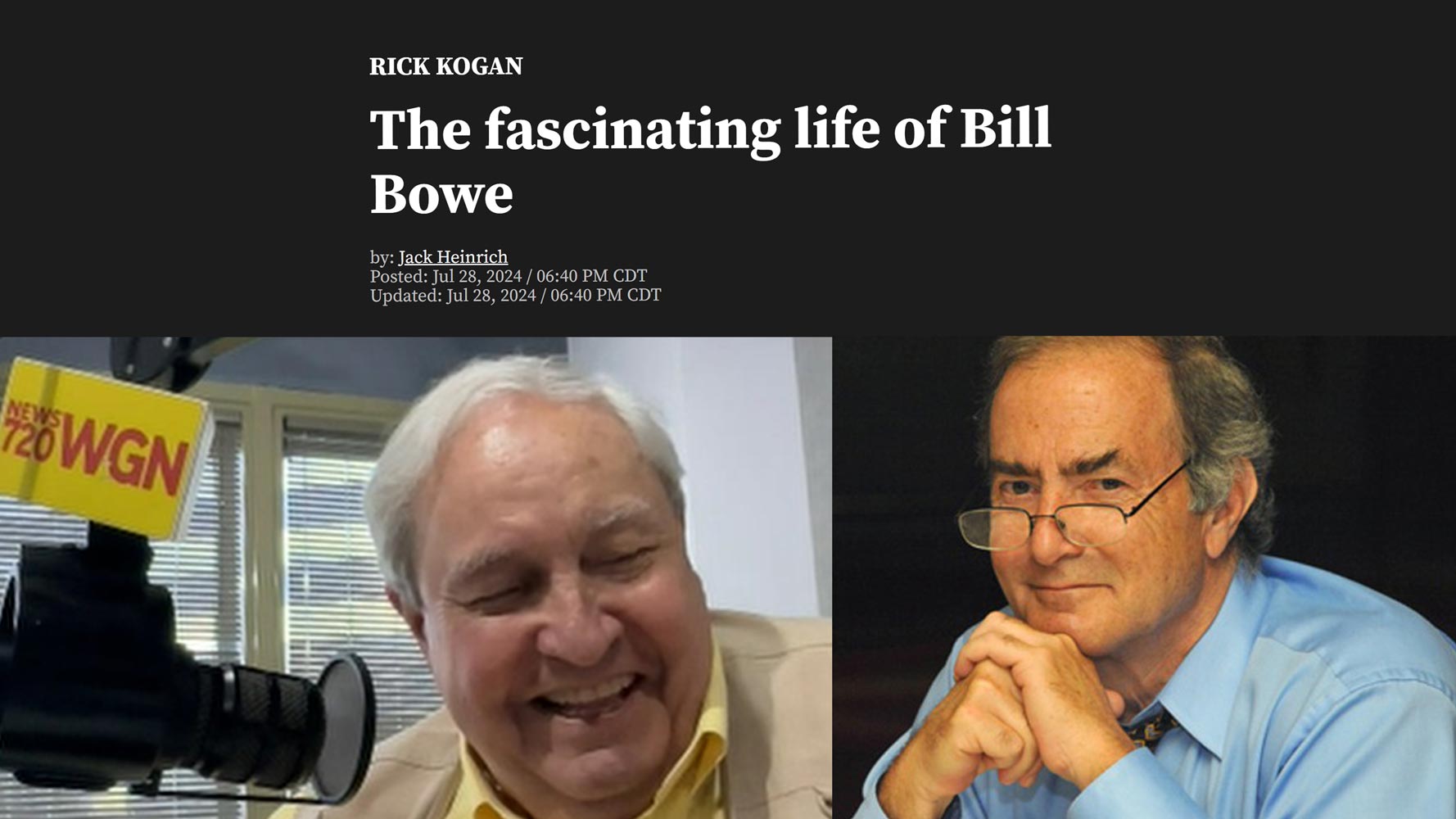

As Ruhe and Geissler headed home, Wechsler phoned Kenny in Nashville and told him to hop a plane to Los Angeles. Kenny, in turn, called new General Counsel Bill Bowe and excitedly broke the news. “I’ve made reservations for you to fly to Los Angeles,” he told Bowe. “An agreement has been reached that will result in a change of control, a sale of the company, and a working out of the creditor problem.” Bowe’s assignment was to put into ironclad writing, for presentation to Foothill Sunday night, the agreement removing the owners from control of the company. Nogales should have known it wouldn’t have been that easy. Although they had shaken hands on the deal, Ruhe and Geissler were bitter that the men they had hired had just dictated the terms of their surrender. Flying back to Nashville, they craftily plotted strategy.

Back in Nashville Saturday, March 2, Ruhe had decided to welch on the deal and fire Nogales.

I had immediately flown to Los Angeles and hired local lawyer Lisa Greer and her law firm Lawlor, Felix to provide legal assistance and office support for me all Saturday and Sunday.

Lisa Greer Quateman

I was trying to understand and document the agreement for the change in control of the company. Usually this wouldn’t be any different than documenting any other arrangement between parties. The parties on both sides of an agreement are usually represented by separate counsel. With Linda Neal recently leaving her role as UPI’s General Counsel as she prepared to marry, I had succeeded her as General Counsel. This happened to occur at a time when ownership and management were no longer aligned. In fact, they were at each other’s throats. With management of the UPI about to shift from Ruhe and Geissler to Nogales, I was still reporting to the former, but about to the follow directions from the latter. This is a very uncomfortable position for a lawyer to be in because of the expectation on both sides of the equation that you will document an agreement in their favor.

As I increasingly recognized being caught in the vise of these conflicting pressures, I began to ask myself who my client really was. My sympathies were completely with Nogales as I had seen Ruhe and Geissler were rank amateurs recklessly pursuing their own self- interest as they sluiced cash and assets out of UPI. Nogales on the other hand was smart, professional and a born leader. He was likely to have success in leading UPI into an inevitable bankruptcy proceeding and out. Although you don’t normally have to think about who you client is as a corporate lawyer, in this case I had to. And the answer was simple. I was now General Counsel of UPI, and UPI was my client. My client was not one or the other of the feuding parties, my client was UPI. My loyalty and duty were to the enterprise and its current and future welfare, and my role was to simply to assist it in any way I could in surviving a crisis that could kill it.

The earlier verbal agreement between Ruhe and Geissler and Nogales had been short on substance and I spent a fair amount of time Saturday trying to understand what Nogales thought the agreement was. On Sunday, I called Ruhe back in Nashville to make sure his understanding matched up with what I’d learned from Nogales. Ruhe abruptly told me there was no agreement and he wouldn’t be signing anything.

With everything coming to a head, I would be joining Nogales that Sunday night to meet Foothill officials for a briefing at the home of Foothill executive John Nickoll’s Beverly Hills home. The stage was set. Foothill would learn Ruhe and Geissler would not be stepping aside, they would pull the plug on its loan to UPI, and shortly the checks going out to its 1,000 plus employees, including me, would bounce.

Nogales, Wechsler, UPI financial advisors from Bear Stearns, myself and Lisa Greer of the Lawlor, Felix law firm represented UPI when we met that evening in the home of Nickoll. Besides Nicholl, several other Foothill executives were present. When the news of Ruhe and Geissler’s about face was discussed, there really wasn’t much anyone could say. Everyone knew UPI would go down the tubes. It was now merely a question of how and when.

Ann Landwirth Nickoll

Then the phone rang. Nickoll’s wife Ann answered the call in a bedroom and said it was for Nogales. When Nogales got to the phone, it was Doug Ruhe. The conversation was a short one on Ruhe’s side, “Luis, you’re fired!” He then told Nogales he wanted to speak with Ray Wechsler. Nogales returned to the group and reported on his conversation with Ruhe. Wechsler said, “Luis, just tell Doug I’m too busy, I’m in a meeting right now. What do I want to talk to him for and get fired?”

Everybody had a good laugh except me. I did my unwelcome duty as General Counsel and went into the bedroom and picked up the phone. Ruhe immediately shouted, “Go in there and fire Wechsler, fire Lawlor Felix, fire Bear Stearns, fire Levine!” Levine was Boston bankruptcy attorney Rick Levine. Though not present, he had been advising me on the finer points of a possible bankruptcy proceeding.

John Nickoll and the others sat quietly as I returned from the bedroom. Though I took a stab at it, it’s hard to publicly fire half the people in a large room with any degree of dignity. Based on accounts of those present, the reporting in Down to the Wire records the scene this way:

Watching Bowe uncomfortably playing the role of angel of death, John Nickoll feared for both his company’s substantial investment and the fate of UPI. Nogales’s leadership had inspired confidence among the very employees and clients Ruhe had so badly alienated…. Nickoll was simply not going to stand still while Foothill’s investment was in jeopardy. He went to the bedroom and picked up the phone. Ruhe was still on the line. “Doug, you’ve got to be crazy! UPI has no management. Foothill has nobody to deal with. You’d better get out here immediately and talk to Nogales and come to some sort of agreement.”

UPI’s Bankruptcy Unfolds with a Shock

It has never sounded quite right when I tell people that as a result of my legal advice, UPI declared bankruptcy. But that’s what happened in short order. Kenny and other UPI senior executives followed Nogales’s abrupt departure and resigned. As predicted, after many previous close calls, paychecks around the world finally began to bounce. Correspondents in Asia and Europe lit up the internal UPI wire with queries and to how they would get back to their homes in the U.S. if the company could no longer afford to buy their tickets home. UPI Bureau rent parties were organized.

Luis Nogales, UPI CEO

In late March 1985, the dust had settled sufficiently so that Time Magazine reported recent developments this way:

In the nearly three years since Nashville Investors Douglas Ruhe and William Geissler acquired ailing United Press International from E.W. Scripps for $1, they have slashed costs, reduced staff and cut wages 25%. For a time, the medicine seemed to work. When U.P.I. announced a $1.1 million profit in the fourth quarter of 1984, its first gain in 23 years, the owners predicted profits of $6 million in 1985. That view was overly optimistic. Last week, with payroll checks bouncing and losses again mounting, Ruhe and Geissler agreed to step aside as part of a deal to save the firm. Under the new plan, they would retain some 15% of the stock but relinquish all control of the news service. U.P.I. President Luis Nogales, who was fired by Ruhe just four days before the agreement, will return to run the company. The terms also call for U.P.I.’s trade creditors to forgive the bulk of its $23 million debt in exchange for a 30% to 40% interest in the firm; most of the remaining shares will be divided among the staff. The creditors, however, may not accept the deal. And even if they do, further cost-cutting moves will be needed if U.P.I. is to survive in the lengthening shadow of the Associated Press.

I had my own personal concerns. Five years before our son Andy had been born prematurely and his medical bills had topped $100,000. Fortunately, most of this amount had been covered in the ordinary course by my then employer’s health insurance policy. Cathy was pregnant again, and again at risk of giving birth early. As feared, our second son Patrick was born prematurely in mid-April 1985, and by the end of the month UPI filed a bankruptcy petition in the federal district court in Washington, D.C. With Pat in an intensive neonatal care unit, Cathy and I were again watching enormous medical expenses pile up daily. When I learned that UPI had stopped paying its health insurance premiums and that the insurance carrier had cancelled its policy coverage, I had thought for some time that the company might go belly up, but I had never thought it might take me with it.

UPI Austin Bureau Rent Party

We were not the only ones potentially out of a safety net. Among the hundreds of UPI employees caught short by the bankruptcy filing, some were in the midst of cancer radiation treatments and others were facing necessary surgical procedures they couldn’t pay for. While all of the UPI employees had suffered financial hits from UPI’s descent into bankruptcy, the trade creditors of the company really took a bath. Thankfully, not all humanity was lost in the proceeding. U.S. Bankruptcy Judge George Bason stepped up to the occasion with the creditors later and sufficient funds were set aside so that the health insurance of all the employees was retroactively reinstated. God bless them!

Prettyman Federal Courthouse

With the bankruptcy proceeding unfolding in the E. Barrett Prettyman Federal Courthouse in Washington, D.C., I began flying every Monday from Nashville to the Courthouse and to UPI’s new offices at 14th and U Streets, NW. Saturday and Sunday would be a welcome family weekend back in Brentwood, notwithstanding the fact that for many weeks much of this time would be spent in the neonatal intensive care unit at Vanderbilt Medical Center.

This travel went on during the summer as the Bankruptcy Court looked into the many questionably dealings of Ruhe and Geissler. By September, a Mexican newspaper owner named Mario Vazquez-Rana emerged to buy UPI out of bankruptcy.

With the seemingly successful reorganization of UPI just completed, I got a call out of the blue from a Chicago headhunter who was looking for a lawyer with publishing experience to head up Encyclopaedia Britannica’s law department in Chicago.

I pursued the job for the great opportunity it was and ended up being chosen for the General Counsel opening. I later learned that over many months there were more than 20 other candidates considered for the position before EB settled on me as their final choice. As 1986 began, I was flying from Nashville into Chicago during the week instead of to Washington, D.C. Until my family joined me, I lived in a one- bedroom apartment not far from EB’s offices near the Art Institute of Chicago. That spring we bought a house in Northbrook, a suburb north of Chicago. It was well located to take advantage of the special needs schooling Andy was about to embark on.

With the family settled, I was ready to dig in my heels and take on the much bigger challenge of Encyclopaedia Britannica.