Kurtis Meyer on Hamlin Garland, Founder of The Cliff Dwellers

Editor’s Note: At The Cliff Dwellers on June 4, 2024, Kurtis Meyer, President of the Hamlin Garland Society presented “Hamlin Garland, Tending Trails,” an overview of Garland’s diverse club-related activities. Garland, the novelist and founder of The Cliff Dwellers, often employed the term “Trails” in his books: “The Long Trail,” “Trail Makers of the Middle Border,” and “Joys of the Trail.” Meyer lives in North Iowa, some

15 miles from where the Garland family lived during Hamlin’s boyhood years. In his talk, he focuses on his research into the many clubs Garland either founded, like the Cliff Dwellers, or those that consumed much of his time and energy. Of considerable interest to current members, Meyer offers a look back at the challenges Garland faced during his years of involvement with The Cliff Dwellers. Meyer has presented other talks on Garland throughout the “Middle Border” states (a classic Garland term) as well as in California, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

Below is the full transcript of Kurtis Meyer’s remarks, Hamlin Garland, “Tending Trails”

Hamlin Garland, “Tending Trails”

“I desire to be remembered by all Cliff Dwellers of today and yesterday.” This is the last sentence of a letter written by Hamlin Garland just days before his death in 1940. It’s on your wall. I am going to broaden the thrust of this sentiment somewhat to include all Cliff Dwellers… of yesterday, today, and TOMORROW. And this evening, my goal is to help us all remember Hamlin Garland.

“I desire to be remembered by all Cliff Dwellers of today and yesterday.” This is the last sentence of a letter written by Hamlin Garland just days before his death in 1940. It’s on your wall. I am going to broaden the thrust of this sentiment somewhat to include all Cliff Dwellers… of yesterday, today, and TOMORROW. And this evening, my goal is to help us all remember Hamlin Garland.

Good evening. My name is Kurt Meyer. I live in rural Iowa, the same county that was home to the Garland family for eleven years, from 1870 to 1881… the setting for “Boy Life on the Prairie”. For several years now, I have served as President of the Hamlin Garland Society, primarily a virtual organization although there are pockets of Garland-related sites and gatherings in both West Salem, Wisconsin, where he was born, and near Osage, Iowa, my county seat, where Hamlin’s family of birth lived after the Civil War.

For the better part of three decades, I have dedicated a small yet significant portion of my time and energy to understanding, interpreting, and presenting to groups such as this the story of Hamlin Garland. In this quest, I have been aided immeasurably by Hamlin himself… after all, he was a writer who wrote often about himself. In autobiography, to be sure, but also in diaries, in letters, and in modestly veiled fictional stories drawn from his direct experience.

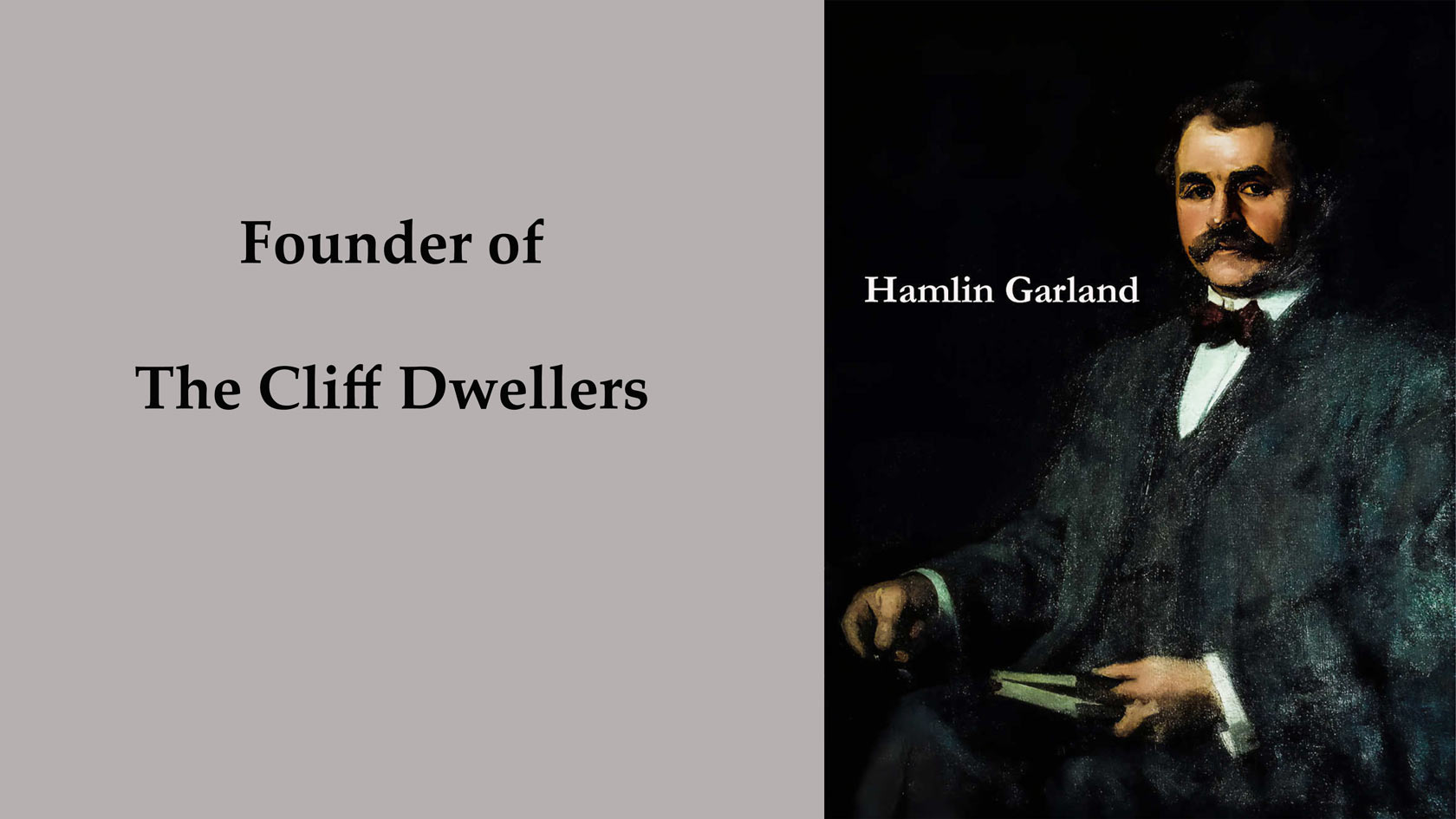

Just as I have devoted a segment of my schedule in pursuit of matters Garland, Hamlin gave generously of HIS calendar, certainly in multiples of what I have contributed, to clubs, primarily social/literary/arts clubs… starting them, sustaining them, advocating on their behalf. Almost every capture of Garland’s life credits him with founding the Cliff Dwellers. You honor him permanently with his prominent portrait… you also honor him by hosting me tonight. I’m most grateful.

If I speak this evening about Hamlin as I might talk about a friend, it’s at least partially because I’ve come to know this person, although he met his Maker almost 14 years before my birth. I hope that through my comments this evening, you’ll also come to know him, or know him a bit better. I chose for my title, “Tending Trails,” because Garland so often employed the term “Trails” in naming his books, “The Long Trail,” “Trail Makers of the Middle Border,” “Joys of the Trail,” etc. AND, because any thriving club or association demands the same vigilant tending that trails require. Garland seemed to grasp this concept, perhaps better than any of us.

Let me briefly introduce myself. I am a retired small-business owner, a consulting practice I began in the late 1980s, working with non-profit organizations, counseling them regarding planning, community relations, and fundraising. Most clients were in the Upper Midwest – Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin – although I first learned this practice on the East Coast: Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey.

Occasionally, I’m accused of being an academic, which I quickly correct, noting I’m an “independent scholar”. When I present on Garland at national gatherings of the American Literature Association, my badge says, “independent scholar,” which is generally translated as “looking for a job.” Trust me. I am not!

My wife and I have been married for 46 years and she would be here this evening but for grandchildren childcare duties. Paula and I split our time between North Iowa and the Twin Cities, “country mouse – city mouse” a two-hour drive apart. We journey often to Chicago, the primary draw being two daughters and their husbands, and four of the world’s greatest grandchildren.

Let me also give you a thumbnail sketch of dear Hamlin. Some of you are already well acquainted, others somewhat less so. He was born in September, 1860, in West Salem, Wisconsin, just east of La Crosse. Two months later, a country lawyer from Illinois was elected to the highest office in the land. Hamlin’s father, Richard, was a restless farmer, a “golden harvest” always just over the horizon, which resulted in frequent moves for the Garland family, which included four children… two boys, two girls.

Some of Richard Garland’s restlessness may have transferred to his son for, as an adult, Hamlin moved from the Midwest to Boston, then to Chicago, eventually New York, and finally, Los Angeles. Hamlin married, had two daughters, and supported his family solely though his writing, something he pursued with persistence and determination. Garland was a literary trail-blazer… ahead of his time in several ways.

For example, Garland was among the first authors providing a realistic portrayal of farm life, an agrarian realist… who depicted rural life as it was, as he experienced it directly, in Wisconsin and Iowa. (Bear in mind, a century ago, one-third of the US population WAS rural. Today, this figure is less than one percent.) Garland’s stories were a counterbalance to the stereotypical “happy farmer,” whistling while headed out to slop the hogs.

Garland told the truth about frontier farmers, men AND women. Rooted in a deep connection with his mother, he was unusually sensitive to the plight of farm women. Garland’s rural views were those of a native: (quote) “I see life from the working side of the fence, not from the buggy of the visiting city novelist. … The beauty of the scene is there truly enough, but beneath it all are pain and squalor.” Hamlin’s first book, “Main-Travelled Roads,” published in 1891 – six fictional, short stories written while living in Boston – drew extensively on his Midwest background. Many critics regard it as his finest work… it propelled him into the literary world while barely in his thirties.

According to literary historian Carl Van Doren, before Garland, authors wrote about the frontier from the perspective of its VICTORS; Garland featured lives of its VICTIMS: the soldier returning from war, a tenant squeezed by his landlord, a son neglected by parents, (quoting Van Doren), “and particularly the daughter whom a harsh father or the wife whom a brutal husband breaks – the most pitiful victims of them all.”

Let me make a point you’re unlikely to hear from other Garland scholars. Garland has not yet received his literary due for his pioneering work in developing arguably America’s most distinctive contribution to world literature: the western. Garland’s fictional novel, “The Eagle’s Heart,” featuring a cowboy hero, is a quintessential western, preceding by several years Owen Wister’s “The Virginian,” a book more well-known and often referred to as “the first western”. I seek to correct this impression… stay tuned.

Summing up Garland’s achievements as an author, Garland scholar Joseph McCullough observes that (quote) “Garland was a capable (not an outstanding) writer, admired for his powerful style, for the vivid impressions he created, and for the moving and sensitive treatment of his themes. He could create pictures and scenes and capture feelings and attitudes in memorable ways. Garland reflected in his works the most vital intellectual, social, and aesthetic ideas of his time, responding as a zealous reformer to such issues as the rise of Populism, Indian rights, women’s rights, evolution, and impressionism.”

Of course, I’m not here tonight to talk about Garland’s literary merits, but rather his diverse and sustained “clubbing” activities. As the world’s foremost living Garland scholar, Keith Newlin, notes in his definitive Garland biography, “He was the founder of many influential literary organizations that still exist, among them the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Author’s League of America, the Society of Midland Authors, the Cliff Dwellers’ Club, and the MacDowell Colony…His accomplishments reveal (among other qualities) a genius for friendship and a rare talent for organization.”

[I note with special appreciation the relationship between the Society of Midland Authors and the Cliff Dwellers. I believe Hamlin would be pleased.]

Probably the FIRST organization Hamlin came to know, he encountered in my rural neighborhood: the Grange, officially The Patrons of Husbandry, an organization founded in 1867 to advance the economic, social, and intellectual station of farmers. The local Grange chapter held regular meetings – monthly, semi-monthly, sometimes weekly – and, as Newlin notes, “farm families eagerly embraced the Grange’s social mission. At these meetings, (teenage) Hamlin learned a lesson he never forgot: that social organizations, formed to improve the lot of others while also providing pleasant company can do as much for the social good as any overt political activity. This principle would inform every one of the many organizations he would eventually found or join.”

Let me note here, the constraints of time – and perhaps minimal interest on your part – keep me from listing (or discussing) all the many organizations Hamlin founded or joined, attended or advocated on behalf of. By loose count, there are five-dozen-plus such entities. Writing is a solitary profession. No easy water-cooler chatter… no comfortable camaraderie at the copier. Accordingly, Garland connected with almost every arts and letters group where two or more were gathered. Of course, many of these entities he helped launch or, at a minimum, served faithfully in a leadership role.

But I do wish to focus on a short list of these groups, guided in part by Garland himself. So, the clubs most important to Garland at one point in his life (admittedly, a somewhat arbitrary choice): “The Players,” the “MacDowell Club,” and the “National Arts Club” in New York. And in Chicago, the “Little Room” and the “Cliff Dwellers,” plus the “Eagle’s Nest,” a camp/club, one-hundred miles west of the city.

Long before Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, Hamlin Garland was the quintessential networker: friend and colleague to many of the public figures of the day… in the world of arts and letters to be sure, but also in such realms as politics, academia, business, and industry. I will say a bit about these various entities before concluding with thoughts on WHY, what motivated Hamlin Garland to engage in club-related activities… what he SOUGHT, what he BROUGHT, and, importantly, what he left and what he took away.

I quote from a framed note on Cliff Dwellers’ walls, written by Garland just days before his death in 1940 about Chicago three-plus decades before: “I had long perceived its lack of any literary association. It had no club where writers and authors could habitually lunch or dine. In New York City, where I had lived for several years, and in which I still spend part of my time, I enjoyed membership in the Players, the National Arts, and the MacDowell Club. In truth, I had helped to form both the National Arts and the MacDowell Club.” This guided my choice of New York clubs upon which to focus. First, The Players.

———————-

THE PLAYERS

“We do not mingle enough with minds that influence the world,” Shakespearian actor Edwin Booth said of his colleagues. “We should measure ourselves through personal contact with outsiders…I want my club to be a place where actors are away from the glamour of the theatre.” Shortly after Booth wrote these words, he and fifteen of his professional friends incorporated The Players in New York City.

In 1888, Booth purchased a building on Grammercy Park and deeded it, plus his works of art, his theatrical memorabilia, and an extensive personal library to The Players. In its first hundred years, club membership was limited to men. Then, in 1989, on Shakespeare’s birthday, thirty women of the theatre, arts and letters, and journalism were inducted. Today, The Players, in its own words, “thrives as place to meet and mingle with artists and arts lovers in an atmosphere of good-natured fun. It is singular among New York clubs in its warmth and high spirits and is treasured by its members and the creative communities with which it has long been associated.”

The Players (often inaccurately called The Players “Club”) is reportedly the City’s oldest social organization in its original facility. Players’ members consist of local pillars of society, prominent bankers, lawyers, business men and women, as well as those identified with the arts – actors, writers, journalists, sculptors, architects and painters. Long before he lived in New York, Garland was accepted into membership, which not only provided gentlemanly conversation with writers and artists, something Hamlin longed for, but also enabled him to use the club as a mail drop and a temporary office – assets for one traveling often to the City.

And yes, it provided contacts. For example, quoting from a Garland biography. “The Players was practically deserted in the post-holiday doldrums as Garland sat brooding in the lounge. Suddenly the clouds rifted as George Brett, of Macmillan and Company approached and drew up a chair. He proposed that his firm pick up three of the old Stone & Kimball titles with an advance of $500 against future sales.”

Simply stated, “cutting deals” requires access and opportunity. AND a venue where it can all take place.

Unlike many of the clubs I’ll discuss tonight, Garland was not a founder, an officer, or an especially significant member of The Players. Eventually, he grew a bit weary of organization and its membership and moved his allegiance to The Century Club. But that change was still decades into the future.

MacDOWELL Club of New York

The MacDowell Club of New York City was founded in 1905 in honor of composer Edward MacDowell to foster appreciation of the fine arts. The Club became a significant force in the artistic and cultural life of the City in the first half of the 20th century, finally disbanding in 1942. And yes, Garland, a friend of MacDowell, regarded himself as a founding member.

The purpose of the club, as set forth in its articles of incorporation, was: “To discuss and demonstrate the principles of the arts of music, literature, the drama, painting, sculpture, and architecture, and to aid in the extension of knowledge of works especially fitted to exemplify the finer purposes of these arts, including works deserving wider recognition, and to promote a sympathetic understanding of the correlation of these arts, and to contribute to the broadening of their influences; thus carrying forward the life purpose of Edward MacDowell.”

(Although founded near the same time, by some of the same people, the MacDowell Club of New York remained a separate entity from the MacDowell Colony, its name recently shortened to just “MacDowell”, a prominent artist’s residency program in Peterborough, New Hampshire, still in existence today.)

Edward MacDowell (1860-1908) was among the first American composers to attain international fame. After studying music abroad, he returned to New York, the city of his birth, serving as the first professor of music at Columbia University in 1896. He left Columbia eight years later in a dispute about the role of the music department. Shortly thereafter, his mental and physical health declined abruptly, and MacDowell died in 1908 at the tender age of 48. Prior to his death, MacDowell colleagues formed the MacDowell Club of New York City to support the composer and advance his ideals.

The club offered performances, recitals, exhibitions, and lectures. The New York club’s roster included well-known writers, artists, musicians, actors, and architects, including Garland, Richard Watson Gilder, John Dewey, Robert Henri, and George Bellows. In addition to the New York City chapter, there were active MacDowell groups chartered throughout the country. At its peak, just prior to World War II, there were approximately 400 independent MacDowell clubs in the U.S.

NATIONAL ARTS CLUB

A third New York City group, the National Arts Club was founded in 1898, under the guidance and leadership of author and poet Charles De Kay, literary and art critic for The New York Times. And again, Garland was involved, part of a coterie of distinguished artists and patrons who envisioned a gathering place to welcome artists of all genres plus art lovers and patrons. The mission of The National Arts Club is to stimulate, foster, and promote public interest in the arts and to educate the American people in the fine arts.

At the turn of the 20th century, American artists began to look to our own country rather than to Europe for inspiration – something strongly advocated by Garland – and the American art world was vibrant. Within a decade, the newly-formed group had outgrown its first facility and moved into more spacious quarters, the Victorian Gothic double brownstone that once belonged to former New York governor and presidential candidate Samuel Tilden, very near The Players.

Club members have included Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Early members included American artists Robert Henri, Frederic Remington, and William Merritt Chase; collectors Henry Clay Frick and J. Pierpont Morgan; writer Mark Twain; and photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Daniel Chester French, and Paul Manship were also members.

From its inception, the National Arts Club admitted women on a full and equal basis; as the Club notes, it distinguishes itself through inclusivity. De Kay and other founders always acknowledged the importance of female artists. The Club was also early in recognizing innovative art media, including photography, film, and digital media. I was struck by a quote attributed to one of the Club’s longtime members, the late artist Will Barnett: “Big cities need organizations that bring people together with similar interests.” I’m certain Garland would concur.

It’s worth noting, Garland’s investment in the three aforementioned organizations all took place while he lived elsewhere, in Boston until the early 1890s and then in Chicago, moving here in 1893, relocation prompted by both personal and professional reasons. Foremost, he sought to be closer to his aging parents, as he helped them relocate to West Salem, Wisconsin, reachable via an overnight train from Chicago.

Garland was also responding to the distinct professional lure of Chicago. In the aftermath of the Columbian Exposition, there was a fresh dynamism in the city, a stimulating atmosphere, a readiness – an eagerness – for the next century, which Garland intended to play a part in. But dynamic futures require institutions to support them. As Garland turned toward Chicago, he set out to help guide and assist the city’s literary trajectory.

THE LITTLE ROOM

Garland arrived in Chicago in his early thirties, a time of increased recognition as an author with considerable promise. Soon, he was invited to give a “salon lecture” in a socially prominent home, where he spoke on the topic of “Impressionism in Art,” a movement then emerging in the U.S. art world. Garland had already done his homework on this topic while living in Boston.

This gathering was significant in Garland’s life path, for at the conclusion of his remarks, an attendee approached and introduced himself. Lorado Taft was primarily a sculptor but lectured broadly on the arts to groups like the one assembled that evening. Taft was eager to connect with Garland… and vice versa. Nurtured by mutual admiration, this friendship would endure for four decades, until Taft’s death in 1936. Importantly, within a handful of years, in 1899, Garland would marry Lorado sister, Zulime.

At the time, new thinking was sweeping through Chicago, a surge of positive energy, starting before the new century and extending shortly thereafter… quoting one analyst: “Darwinism, Progressivism, Social Gospel (and its antithesis, Fundamentalism), Modernism, Realism, Imperialism and, on the lighter side, Jazz. Law was moving away from the Absolute and the concept of Individualism was predominate.” More than most, Lorado Taft was tracking on these changes, inviting his new friend Hamlin Garland to “come over and discuss these ‘isms’ with me.”

Hamlin was a most willing participant. Perhaps as an outgrowth of his solitary work, Garland sought camaraderie when not placing words on paper. He reveled in Taft’s companionship and gravitated to Taft’s studio late afternoons. Before long, others joined in, finding an accepting community among like-minded individuals. One often stopping by was Henry B. Fuller, then, a writer of novels set in Europe. Over the years, Fuller and Garland formed an unusual but enduring friendship important to both men, which, like Garland’s relationship with Taft, lasted until Fuller’s passing in 1929.

Shortly after they began spending time together, Garland, Taft, and Fuller formed an organization they called, “The Little Room”. Ostensibly, the group’s purpose was to provide a setting for artists, writers, and intellectuals to socialize, formalizing what these men sought and found in Taft’s studio. Its members included reformer Jane Addams, architects Allen B. and Irving K. Pond, dramatist Anna Morgan, painter Ralph Clarkson, illustrator and publisher Ralph Fletcher Seymour, and at least five writers of note: George Ade, Henry Blake Fuller, Harriet Monroe, Edith Wyatt and… Hamlin Garland, an impressive array of painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, architects, and others engaged primarily in arts-related professions. Note: both genders welcome.

The Little Room provided a much-needed sense of community, a place to share ideas, resources and fun, an inkling of what an urban culture of letters could be. Deriving their name from a short story by Madeleine Yale Wynne — “the story of an intermittently vanishing chamber in an old New England homestead.” Little Roomers gathered in different studios located in the Auditorium Hotel and, eventually in the Fine Arts Building for afternoon teas and midnight dramas, fostering an atmosphere of aesthetic playfulness and serious intellectual engagement, a platform to discuss arts-related AND complex social issues, that lasted until the club’s demise in 1931.

Sometimes the coterie met on Saturday afternoons for potluck “camp supper.” This was the genesis of “Eagles Nest,” which I will discuss momentarily. Guests were always welcome at the Little Room and generally would be asked to create or perform, a dance, a vocal solo, or some such.

Little Room records from the early 1900s include an emerging proposal to form a separate entity, a men’s organization, initially called The Attic Club, a step that took place in 1907. Two years later, this start-up entity assumed a new name: The Cliff Dwellers. My intent is certainly to give the Cliff Dwellers and Garland’s role in it the attention it deserves. But first, I wish to deviate slightly and follow up on the camp/club that Little Room stalwarts gave birth to… out in the country.

EAGLE’S NEST

Before traveling further down the trail of Garland’s Chicago activities, we must note an entity that came together among those seeking an escape from city life. As noted, in its early days, in addition to their regular gathering time, the Little Room group would assemble periodically on Saturday afternoons for a potluck “camp supper”. Seeking a way to sustain this atmosphere, members soon embarked on an effort to find a permanent campground, in this instance, at a location one-hundred miles west of the city.

In the late ’90s, efforts to take The Little Room out to the country led to formation of “Eagle’s Nest Camp” near Oregon, Illinois, 13 acres of forest on a Rock River bluff. Unlike the Cliff Dwellers, where Garland is prime founder and Taft, a founding member, at Eagle’s Nest, Taft is principal founder and Garland, a founding member.

In addition to Taft and Garland, charter members included attorney Wallace Heckman, the property owner; artists Ralph Clarkson, Oliver Dennett Grover, and Charles Francis Browne, authors Henry B. Fuller and Horace Spencer Fiske, editor James Spencer Dickerson, architects Allan B. and Irving K. Pond; and composer Clarence Dickinson – trustees dedicated to pursuit “of the fine arts, literature, and the professions.” Note: like Garland, artist and Eagle’s Nest founder Charles Francis Browne also married a sister of Lorado Taft, in Browne’s case, Turbulance Doctoria Taft, a name generally shortened to “Turbie”.

Campers staged outdoor plays, lectured, and contributed paintings to exhibitions at the local library. Members were responsible for at least two lectures a year, either on the property or in the nearby community, an intentional effort to promote art education, which was always central to Taft’s thinking. In its early years, camp was an accurate description… basically, city dwellers “roughing it”.

Initially, camp staff consisted of Taft’s sister, Zulime, responsible for managing the site and tending to meals and supplies. Zulime assumed this role having served in a similar capacity at her brother’s studio. She had studied in Europe and was hopeful of becoming an artist, something her brother sought to advance among the talented females affiliated with his studio. At camp, Zulime was soon taking long after-dinner walks with Hamlin Garland, ten years her senior. Garland tells of their courtship in “Daughter of the Middle Border,” the book that earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1922.

All the artists at Eagle’s Nest seemed to communicate a unified message of beauty, although it’s hard to determine whether this was part of Taft’s central strategy or an outgrowth, a by-product of sorts. The important result is that a central message of beauty was being pulsed out, in rural Illinois, within the city of Chicago, and, to a lesser degree, throughout the state and nation.

Lorado Taft’s “Black Hawk,” a massive, reinforced concrete sculpture, was a lasting gift to the colony at Eagle’s Nest. Following Taft’s death in 1936, the Camp’s lease continued until the death of the last original signer, artist Ralph Clarkson, painter of Hamlin’s portrait hanging above the fireplace, died in 1942. In 1950, the property was bought by Northern Illinois State Teachers College (now Northern Illinois University).

THE CLIFF DWELLERS

More than any other single individual, Hamlin Garland is the Cliff Dwellers’ founder. So, let’s hear from the founder, in words written days before his death, displayed on these walls (although I’m under no illusion that you reacquaint yourself with these comments each time you enter).

“Early in 1907, I said to Henry Fuller, Lorado Taft, Charles Francis Browne, and Ralph Clarkson, ‘If you will aid me, I will undertake to organize, here in Chicago, a club similar to the Players composed of artists, writers, and musicians.’ With the exception of Henry Fuller, all agreed to the plan and helped me to draft a letter to be sent to a select list of men representing sculpture, painting, architecture, music, fiction, poetry, and the drama, outlining the idea of such a club and inviting their cooperation.

With an acuteness for which I took little credit at the time, I suggested that a quota of distinguished laymen, like Charles L. Hutchinson, Frank Logan of the Art Institute, the presidents of nearby universities and business men of literary and artistic sympathies be included in our list.

This letter brought me nearly one-hundred acceptances of membership in the proposed club and in our first meeting I was elected chairman of our board of directors – a position which I held until I moved to New York City in 1913. As a majority of our members voted that it should be located in the Loop, we decided (after much discussion and search) to build a bungalow on the roof of a building.

… At my suggestion, we called ourselves the ‘Cliff Dwellers,’ the name of a novel by Henry Fuller… the adoption of this name had the surprising effect of keeping Henry Fuller from accepting membership in this club. The club at once became what we had hoped it would become; a lunching place for local writers and a place where fellow-craftsmen could be entertained. Its influence widened year by year. The role of its membership bears witness to its power, and its continuance for a third of a century is evidence of its value.”

The name “Cliff Dwellers” was a substitute for Attic Club that had been proposed earlier. Until officers could be elected in 1908, an impressive list of Chicago literary and artistic leaders was assembled to advance the organization, including Garland and Taft, plus ten others. Dues were set at $40 a year.

The Chicago Tribune described the organizational meeting, “The cliff will be a modern skyscraper, not a real cliff of stone, such as afforded lofty abode to the cliff dwellers in New Mexico.” Members’ original intent is described on the Cliff Dwellers’ website, “It was the purpose of the founders of The Cliff Dwellers to establish a place where people seriously interested in the arts, both professionally and as committed observers, could come together in a congenial and friendly way.”

From two different letters written by Garland after the organizational meeting: “This club is modelled directly after The Players and The Century Association of New York City.” And, to a second correspondent: “I know you will be interested in the new club which I have helped to organize in Chicago. It is a kind of Century Club – a union of writers, painters, sculptors, musicians, actors and architects in Chicago and vicinity. It is the first successful attempt at bringing these elements into one organization and as its president I am anxious to have it start off happily.”

At the dedication ceremony January, 1909, the featured speaker was member Charles L. Hutchinson, who in 1882 at the age of 28 helped found the Art Institute of Chicago and served as the museum’s president from that year until his death in 1924. Mr. Hutchinson concluded his remarks that evening on this note:

Why do you look for a new Heaven and a new Earth in vanished things and outworn uses when all the time those Kingdoms are within you and their glory is still to be revealed? Let us come to the Club in such a spirit; bring to it the best of all that lies within us, of experience, of culture, of good fellowship and good cheer, and we will soon make this place a shrine, not only of pleasure, but of inspiration.

The more we give the more we shall receive. Let us embrace the wealth of opportunity offered by the present, and rejoice in it and, perchance, in the future some prophet will arise and bemoan the fact that we and the glories of our present have passed away. Let us ask not what can the Club do for us, but what I can do for it.” NOTE: Sentiments were expressed similarly at a presidential inauguration five decades later.

According to the Articles of Incorporation, the Cliff Dwellers was formed to “encourage, foster, and develop higher standards of art, literature and craftsmanship; to promote the mutual acquaintance of art lovers, art workers and authors; to maintain in the City of Chicago a club house and to provide therein galleries, libraries and exhibition facilities for the various lines of art, in support of the foregoing purposes.”

Frank Lloyd Wright was a charter member; Louis Sullivan, for whom the library here is named, wrote his memoirs at a small oak desk, still in the library, I believe. The revered architect was down and out at the time – some would add broke and drunk – when he penned: “The Lake is there, awaiting, in all its glory; and the sky is there above, waiting, in its eternal beauty; and the Prairie, the ever-fertile Prairie is awaiting,” Notably, when Sullivan died in 1924, Cliff Dwellers’ members donated funds for his burial and memorial at Graceland Cemetery. Carl Sandburg and James Whitcomb Riley had meaningful associations with the Club as did Daniel Burnham, landscape architect Jens Jensen, and of course a great many other civic and cultural figures.

In its early years, Poet William Butler Yeats (Yates) was honored at a banquet attended by 150 people at The Cliff Dwellers in March, 1914. Poetry magazine was then two years old and hosted the gathering. Until forty years ago, 1984, Cliff Dwellers was an all-male club, however, Poetry editor Harriet Monroe used this occasion eleven decades ago, to access the Cliff Dwellers’ affluent clientele. Monroe teamed Yeats with Vachel Lindsay, the Springfield poet, reading for the first time publicly, The Congo.

At one point, Garland wrote a short poem that captures the club’s philosophy:

Down in the city’s deeps we meet in savage fashion,

And play as best we may the selfish, sordid game,

But after hours and up in the Cliff Dwellers:

Man greets his fellow man, and only then remembers,

Art’s magic bond of light, and beauty’s bloodless stain.

Without question, Hamlin devoted himself to promoting the Cliff Dwellers, in essence, doing whatever he could to fortify the organization as he saw it. Repeatedly, in biographical works covering Hamlin’s Chicago years… AND in the author’s autobiographical works… one encounters statements similar to “Garland continued to occupy his time with work for the Cliff Dwellers…”

Ah, perhaps his grip was a bit TOO tight. I’ll let my Garland colleague, his biographer Keith Newlin, explain, writing here about late 1914, early 1915. “Trouble was brewing at the Cliff Dwellers. Czar Hamlin the First, as he was known to members, had become increasingly imperious in his management of the club. He refused to permit alcohol on the premises; he issued a directive that no women were permitted in the club until after 6:00PM (for fear of upsetting the business lunches that had become commonplace) and at one point he ‘demanded that a house rule be passed forbidding public smoking of cigarettes by females in the club rooms.’ Members wearied of Garland’s imprimatur, and on December 14 plotted a coup; they passed an amendment to the bylaws to restrict the president’s term of office to no more than two successive terms. Deeply wounded… Garland’s friends attempted to smooth over his hurt feelings by hosting a testimonial dinner. The affront of having effectively been kicked out of the club still rankled years later. ‘I expected and predicted that the Cliff Dwellers would bust up when I relinquished the helm much against my will – but I admit I’m wrong – Hamlin Garland’” (That note, too, is displayed on the walls here.)

It may be that it rankled, but age and time generally does soften such irritations… on the part of all participants. Again, I call your attention to Hamlin’s closing sentence. “I desire to be remembered by all Cliff Dwellers of today and yesterday.” Probably fair to say in response by the Cliff Dwellers, “Back at you, old friend Hamlin!”

CONCLUSION

So, what’s our take-away today? What should we think about these glorious, venerable organizations, entities that meant much to many, but specifically to Hamlin Garland? What drove him to devote countless hours to tending to club trails… in many cases, being the trail blazer himself?

Frankly, we’ll never know for sure. Much of what follows is speculation, which of course means THIS is the fun part! I’ve given considerable thought to this… but psychoanalysis is NOT my strong suit. Accordingly, I’m eager to hear your theories, too, and will seek your input in just a moment. First, let me share some of my musings at to Garland’s motive. (I hoped to limit these to a smaller, more manageable number… maybe three or four, but confess I’ll now share SEVEN items with you. Apologies in advance.)

First, at its simplest level, Garland engaged in club activities seeking camaraderie and socialization, to meet his abiding need for friendship and fellowship. Looking at it from a more negative vantage point, it was an attempt to overcome isolation and loneliness, qualities all too characteristic of a writer’s calling. As one writer noted of Hamlin, “as was Garland’s practice, the casual contact was not allowed to fade.” Clubs became Hamlin’s rolodex, and yes, I realize that’s a dated metaphor.

Second, Garland sought stimulation. For Hamlin, club activities weren’t just time spent hanging out with buddies. It was an effort to replenish or maybe to jump start his creative juices. For example, as one writer noted after Garland moved back to the Midwest, “In Chicago, Garland missed the congenial association of creative folk at the Players, MacDowell, National Arts, and other New York clubs. Although he has been derided as an inveterate clubman, clubs were as necessary to his craft as pen and ink. He did not work well in isolation and relied on the stimulation provided by other writers and artists.”

Third, Hamlin – and others – joined clubs to create, sustain, and enhance connections, specifically business connections. A place where someone COULD, as happened at the National Arts Club, pull up a chair and offer up a business proposition.

Fourth, to have physical space, which can also be an occupational challenge. (Shall we pity poor Louis Sullivan!) When Hamlin was living out of town (for example, in Boston or Chicago, but clubbing in New York) it was handy to have a New York postal address and a City workspace. Often, clubs provided a highly desirable setting, or as Hamlin once remarked, perhaps partially in jest: “I need the aid of dignified surroundings and appreciative friends in order to keep up my illusion of grandeur.”

Later in life, a club home enabled him to get out of the house. Quoting from Newlin: “A visit to the Century Club would form a part of his daily routine, a habit Zulime would count on. ‘Whatever you do,’ she would tell her children with relief as Hamlin went out the door, ‘don’t marry a man who works at home. Marry one who goes to work at eight every morning and doesn’t come home till five.’” So there!

Fifth, in part because it was mentioned so often, Garland and his colleague / brother-in-law Taft were ever hopeful through club activities of cross-pollinating various segments of the arts & humanities people, then mixing this blend with those from business & industry, to create the dynamic synergy required to move big ideas into action. In many instances, this came about when the spark jumped from the “creatives” to the “connecteds,” which generally meant access to business and philanthropic leaders. For Garland, clubs put into action many of the principles he advocated in his writing and from the podium.

Sixth, clubs were a way to exercise meaningful service, which, long after Garland, became known as “servant leadership”. Hamlin often assumed a key role in clubs: visionary, founder, president. He wasn’t a wealthy man. It was his contribution, a meaningful contribution. Given a certain gift for these pursuits and, increasingly, putting into practice his hard-earned experience, in most ways, Garland was effective.

Seventh, and last, for Garland clubbing was his way of making a mark, of leaving a trace, obviously a supplement to his literary output, of which he was often uncertain regarding its permanence. It was Garland’s ongoing effort not just to BE somebody… but to be somebody IMPORTANT, to be recognized as a man of merit, rising well above life’s modest station he was born into.

Garland saw his gift for organizing clubs as contributing to our nation’s history. For instance, he wrote, “Fuller calls me a ‘club carpenter and joiner’ (but) I take certain pleasure in forming these institutions which … are milestones in the nation’s progress, signs not only of the movements in our cities, but evidence of a developing consciousness of the value of arts and letters in American life.”

Milestones in our nation’s progress, indeed! Thank you, Hamlin, for your determination, your persistence, your tenacity, your resolve. And thank you, friends, for showing these same signs as I’ve shared my overstuffed file on this topic. I want to gather your thoughts, your feedback, your input. And I do so now, with great appreciation for your being here and gratitude for your indulgence. Thank you very much.